ArtSeen

Becca Albee

On View

MIT List CenterList Projects 20: Becca Albee

December 12, 2019 – February 9, 2020

Cambridge, MA

Because we are living in times of overwhelming, and daily, and sometimes unimaginable loss; because we are living in times when the extinction of species and the loss of certain ways of living are considered inevitable, and certain lives “ungrievable,” mourning is a political act. It allows us to be vulnerable, to foster empathy, and opens up a space to catalyze collective resistance against such loss. But how do we mourn without instrumentalizing the lives of those we have loved, especially in a cultural moment that thrives on such parasitism? Becca Albee’s exhibition at the MIT List Visual Arts Center quietly shows us how. Through exquisite turns moving between archival source materials from the life of the artist Robert Blanchon, and still and moving images documenting the spawning of horseshoe crabs, this presentation of her work subtly and carefully compels us to feel a sense of intimate and geologic temporality simultaneously, setting into relief the necessary work of collective grief.

Albee makes four deliberate turns. First is the move from image to title. We are met in a narrow hallway by four delicately framed silver gelatin photographs, which depict trails and traces on a beach, traces that suggest natural processes of erosion and movement of marine life. They make patterns, parallel tracks crisscross, a soft impression in the sand leaves the shape of a heart that almost flutters. We turn to the title card across the hallway and read, Felix dies rather young. So does Joe Orton. Consider the congested matrix we now know as history’s machinery, and draw parallels and opposites as to how one is remembered, by whom, for whose benefit. How many voices are involved? With the artists no longer with us, who speaks for them? Do you always agree with posthumous posturing? (2019). This first turn stabs us, and we realize we are looking at death. The voice of Blanchon from the past speaks presently and adamantly, narrating the work for us. Albee’s use of Blanchon’s writings is a ventriloquism, a kind of spiritual practice where noises from the stomach are the voices of the unliving. Blanchon agitates from the inside.

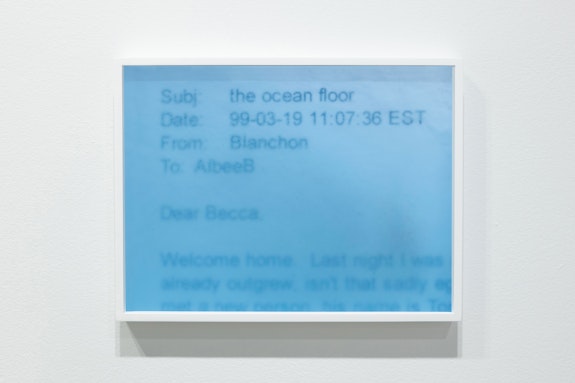

The second turn is to the ephemera found in Blanchon’s archives. Albee re-photographs the materials, selectively revealing parts of objects, dispelling the myth of objectivity through physical manipulations of vibrant color—she lays a piece of cyan lighting gel over the photograph of crossed arms in the frame in one, and photographs a print-out of an email from Blanchon through a blue liquid in another. The email’s subject line is “the ocean floor,” and the opening line, “Dear Becca, Welcome home.” The process of re-photography is a long-explored strategy for artists who use the archive, and here the effect is not to simply suture the past and present, but to suggest the brutal marks of time that are always a part of living, especially in the lives of those dispossessed. In this case, Blanchon’s life ended the way he saw his friends’ lives end: from an epidemic made more fatal by violent homophobia and purposeful inaction by lawmakers.

We next encounter three video monitors, which glow eerily in a darkened part of the gallery. All three are soundless and show horseshoe crabs in low water on the beach, tossed and turned by waves. Sometimes they get flipped onto their backs by the strength of the waves. Their legs flail; they seem defenseless, vulnerable. The videos are mesmerizing, as the crabs look preternatural, appearing fluorescent purple under blacklight flashlights, a bioluminescence that feels otherworldly. I learn that the horseshoe crabs are spawning on the beach, which is at its peak at high tide during full and new moons. I also learn that horseshoe crabs are one of earth’s oldest surviving species, existing for over 300 million years. Humans harvest their blood because it contains hemocyanin and amebocytes, which are used to detect bacterial endotoxins, an extraction process that can sometimes kill the crab. Overharvesting, illegal harvesting, and global warming have all made the horseshoe crab more vulnerable to extinction. The title of the video installation is …my work as a premature memorial to myself, others, and perhaps our world. Now that’s an ending (2019).

In the final turn, we are offered a small stack of photocopies by the gallery attendant, comprising several of Blanchon’s astounding syllabi (he was her teacher in 1999). Blanchon, it seems, approached all of his writing with plain honesty, witty and painful. If there is ever a praxis of “the personal is political,” it is these, which read like short stories and as if he is speaking to you and you alone. No two syllabi are alike in format, content, or tone, and often narrativize the class days (for example, “Dec 1 + 3 You are who you are now that you are no longer just you: Our in-depth, two-day marathon critique of your work”). The syllabi are markers of their era, deeply invested in the identity politics of the time, but also uncannily relevant today. It is not only incredibly overwhelming to feel as if time had come to a standstill, but also a joy to recognize oneself present in the syllabi, to see the political legacy we have inherited drawn as beautifully as horseshoe crab tracks in sand. Those tracks are fleeting but also cyclical: we have lost so much, but we can also endure. Albee’s work suggests that collective mourning is nothing less than the ability to confront time, lovingly, without fear, and to face the truth of our own sorrow, honoring the people who have paved the way for our work.