ArtSeen

ANICKA YI: 6,070,430K of Digital Spit

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Mit List Visual Arts CenterMay 22 – July 26, 2015

Like much of Anicka Yi’s work, the artist’s current solo exhibition at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, “6,070,430K of Digital Spit,” manages both physical restraint and sensory overload. A slim disc of light radiates in the center of the dimly lit gallery, whose floors are carpeted a dusty salmon tone and walls painted the color of dried blood. Three freestanding sculptures fashioned from stainless steel laboratory stands, draped with sheets of “kombucha leather”—a translucent cellulose film that forms as a byproduct of fermentation—dot the remaining space. They double as ghostly surrogate viewers, their gleaming industrial bones shrouded in organic, homegrown skin.

The most insidious element in the exhibition is also the least material: a potent scent of menthol, infused into the gallery’s ventilation system. As it enters the lungs uninvited (there is of course little recourse for escaping smell), it triggers recollections of an institutionalized personal hygiene. According to the accompanying press materials, the scent also stands as an attempt to recover the experience of a palate cleanser at the famed restaurant elBulli, where a waft of mentholated air was released from beneath a sheet of ice, posing inhalation as a mode of tasting. Here, you can similarly taste the air—a sensory doubling that extends to Yi’s fusion of smell, sight, and sound, into one synesthetic situation; the ’80s synths of Soft Cell’s “Sex Dwarf,” edited into innocuous instrumentals devoid of their notoriously risqué lyrics, startle periodically. This element of dubious “taste” introduces another slippage latent in the term—that between biological taste and aesthetic discernment—while the song’s truncation suggests a sanitization that reverberates throughout the exhibition.

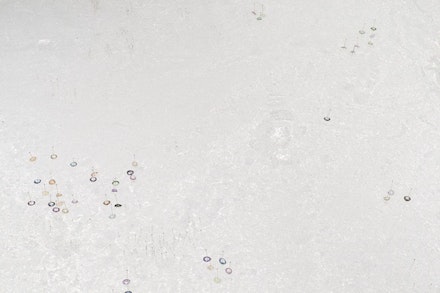

Taken as a whole, these elements speak the dramaturgical language of a stage upon which the central illumination plays protagonist. Along with the olfactory and auditory components, they comprise a work cheekily titled Our Love Is Bigger Than An AIDS Quilt (2015). While at first glance appearing as a mirage of light, the piece is in fact a glittering pool of transparent, gelatinous substance, lit from above and contained by a shallow Plexiglas rim—an absurdly enlarged petri dish, stippled with washes of yellow and dots of blue and green. Refracted within this entropic ooze, the light appears to emanate from its depths, mimicking scientific images of growth cultures glowing dramatically against dark backgrounds.

The petri dish is, of course, fitting, considering the exhibition’s location at MIT, where Yi has been engaged in research over the past year. It is also unsurprising in light of her larger practice, in which unstable, often ingestible materials are placed in metabolic situations, catalyzed towards decay and recombination on a molecular level. For example, in a recent exhibition at the Kitchen, she joined microbial samples taken from 100 women into one bacterial strain cultivated in a vitrine of agar, a natural medium commonly used as the substrate for microbiological cultures. This attention to the minute scale of the cell suggests a concern with breaking through the perceptible surface of materials towards what lies beneath, and its dispersion throughout the body as, in Paul B. Preciado’s words, “soft, feather-weight, viscous, gelatinous technologies that can be injected, inhaled—‘incorporated.’”1

Kombucha being a particularly resonant, if earthy, example of one such “gelatinous technology,” the sheets of “leather” in this exhibition most compellingly reflect this concern with cellular growth and its attendant cultural discourse of self-improvement via ingestion. But, splayed on their metal supports, these swaths of organic matter are far from germinating. Left out to dry, both figuratively and literally, they portend the unexpected fact that the oversized petri dish they surround is more prop than tool. It contains a substance that might present as agar, but is in fact gallons of hair gel. The undulations on its surface are floating projector lenses and the sprouts of color, which masquerade as growths, are actually cosmetic contact lenses. Where the microscope would be located overhead, Yi offers a theatrical spotlight—driving home the notion that despite its apparent scientific materiality, this petri dish is simply a static pool of vehicles for synthetically enhanced vision, whose utility has been replaced by metaphorical value. In an odd twist, Yi offers something that looks like something it is not, while slyly insulting the primacy of looking.

This affront to ocularcentrism finds more literal form in the precise acts of violence visited upon the contact lenses, whose vacant corneas are pierced by thin metal pins. Yi’s pond might display eyes, but denies any narcissistic identification, posing a challenge to the historical connection between vision and ego, the eye and the “I.” With its polite distance between subject and object, vision has long been celebrated within Western thought as the more sublimated, rational, and, as many have noted, “masculine” of human senses. In contrast, the “baser” senses of touch, taste, and smell, have been separated, repressed, and often coded as feminine.2 In this light, the fact that you not only see this exhibition, but also hear and inhale it, takes on a political charge not readily evident in experience alone.

Yi herself has articulated a desire to disrupt sensory compartmentalization, and this exhibition might be the most explicit effort to date. The attempt is not necessarily novel: over the course of the 20th century, many artists have set out to engage senses in excess of vision. As evidenced in the recent penchant for immersive aesthetic situations (Marina Abramović or Carsten Höller’s interactive exhibitions come readily to mind), aspirations towards synesthesia can easily become fodder for an experience economy seeking sensory stimulation capable of satiating widespread distraction. To return to Preciado’s formulation, these experiences simply offer a slightly different kind of sensory “incorporation,” verging on intoxication. With all its theatrics, Yi’s exhibition comes dangerously close.

Yet, these same theatrics differentiate Yi’s practice by shifting the exhibition into a symbolic register that denies any uninhibited experience of material: nothing is quite what it looks, smells, or sounds like, but neither is it pure (and therefore pleasurable) illusion. The materials here abstain from changing states on a cellular level, unlike many of Yi’s other endeavors, but they do corrode any tidy boundary between the biological and symbolic registers. By conflating microscopic matter with gestalt contour, or the molecule with a memory, Yi seems to ask how, through what sense and at what scale, we recognize the meeting of what something is and what it means. In this regard, the exhibition avoids investing fully in either the infinitesimal ontology of material, its experiential bodily effects, or its visual appearance. Rather, by means of sustained shifts between these indices, Yi places emphasis on the cultural and semiotic scaffolds we use to make sense of the stuff of the world as it enters our domain of experience—an effort that might be seen as meta-commentary on her practice itself.

Endnotes

- Beatriz Preciado, “Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics.” e-flux 44 (2013).

- For an in-depth discussion, see Caroline A. Jones, Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg’s Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2005.