As the MIT 2016 celebrations commence this month, commemorating a century of MIT’s Cambridge campus, we are exploring some of the obscure, overlooked or forgotten pockets of artistic activity at MIT from 1916-2016, beginning with this installment on the Department of Architecture’s drawing curriculum in the early twentieth century (1910-20). This series, “100 Years of Arts at MIT,” will highlight the creative work of prominent, eccentric and beloved individuals in the MIT community and will feature the departments, labs and student groups who contributed to the visual and performing arts on campus through the decades.

When MIT moved from Boston to its new Cambridge campus in 1916, the Department of Architecture did not make that “Great Stride” across the Charles River from its location on the corner of Boylston and Clarendon streets. Instead, it returned to its original home in the Rogers Building on Boylston Street, where it held its first classes in 1868. The Rogers Building, with its handsome French Renaissance façade, its spacious neoclassical interior, and its proximity to the Museum of Fine Arts, was a physical embodiment of the ideals of the department, which combined Beaux-Arts training with the most advanced structural studies.

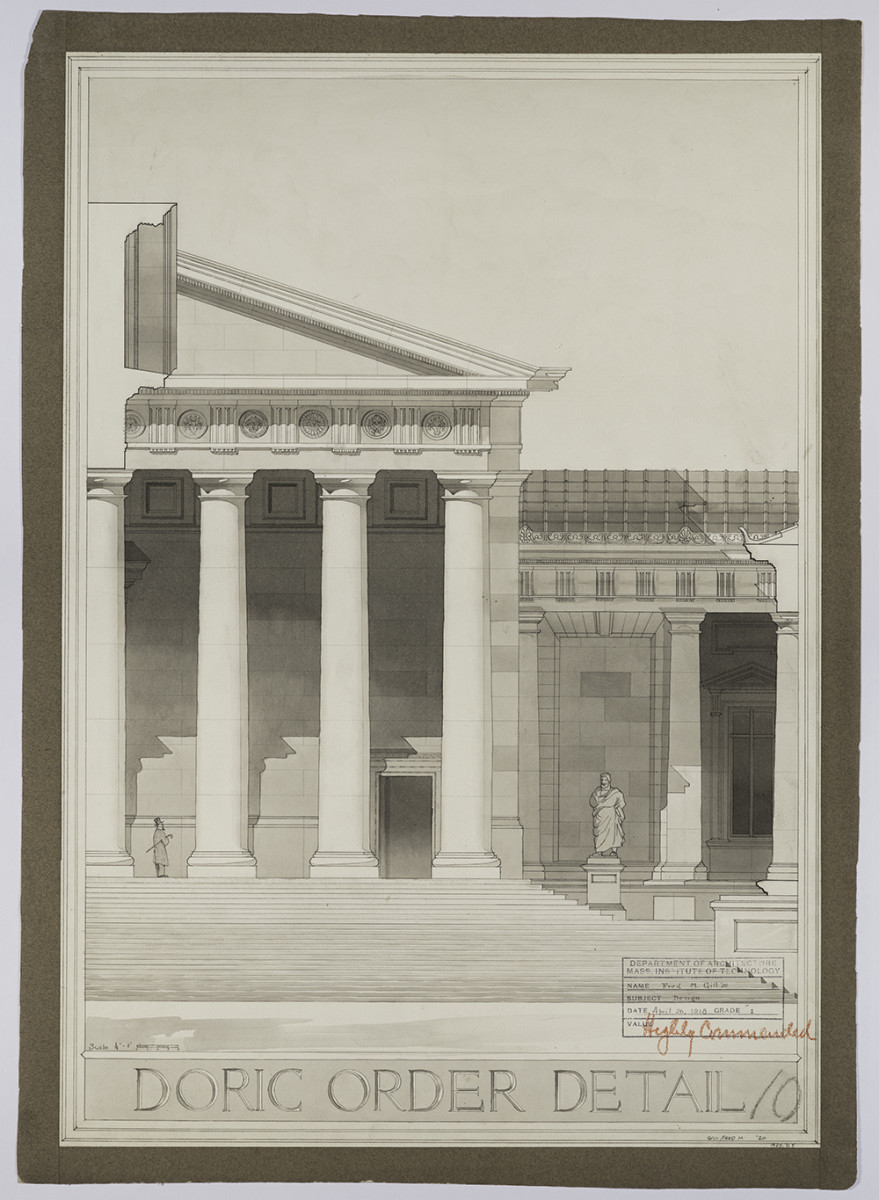

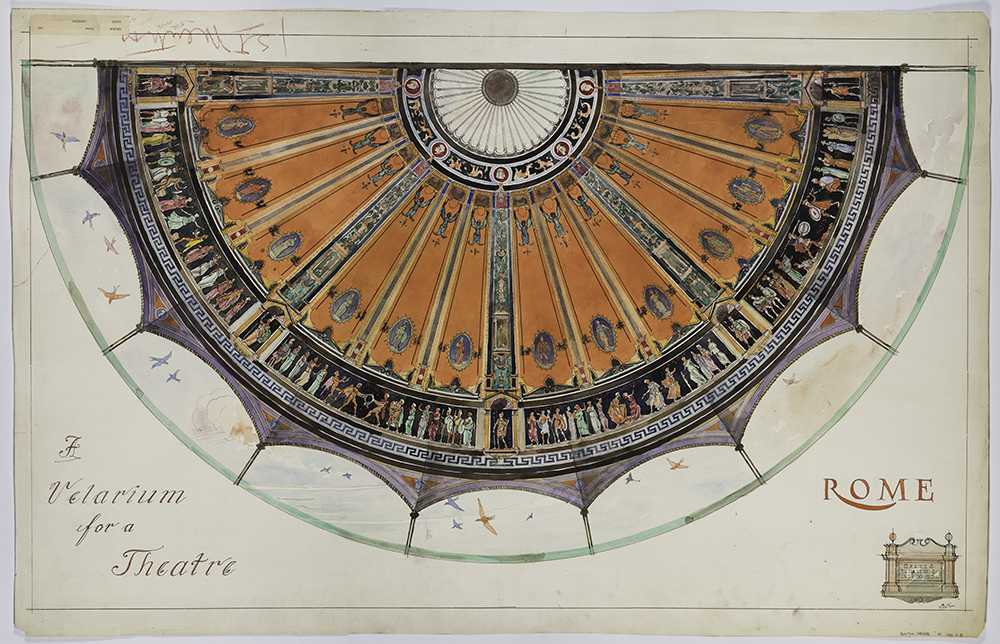

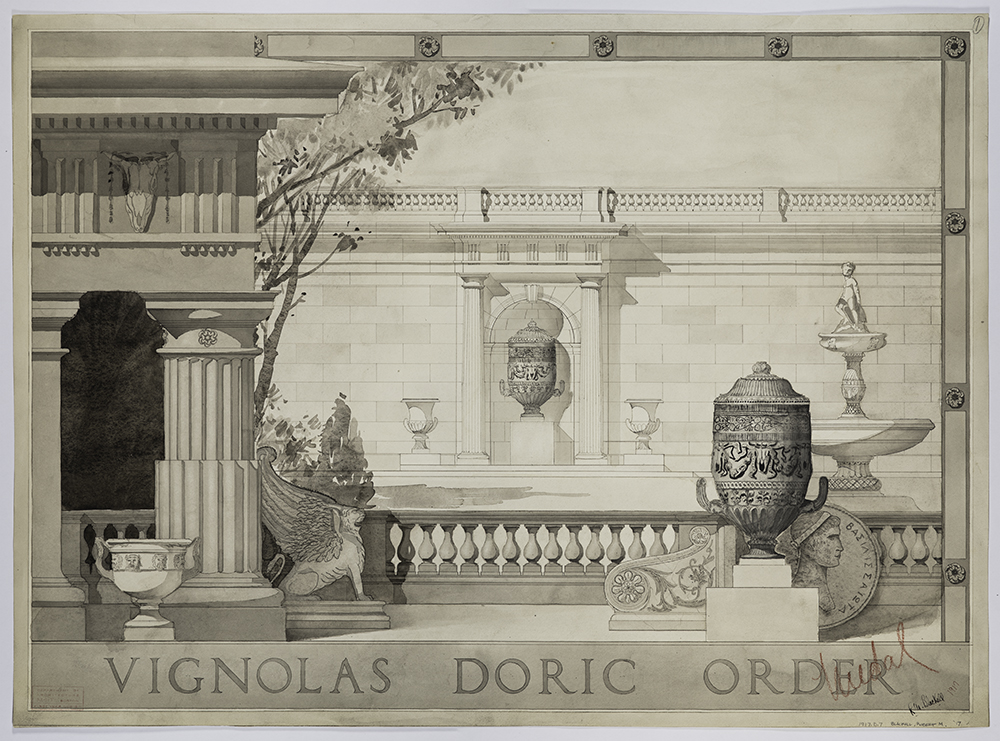

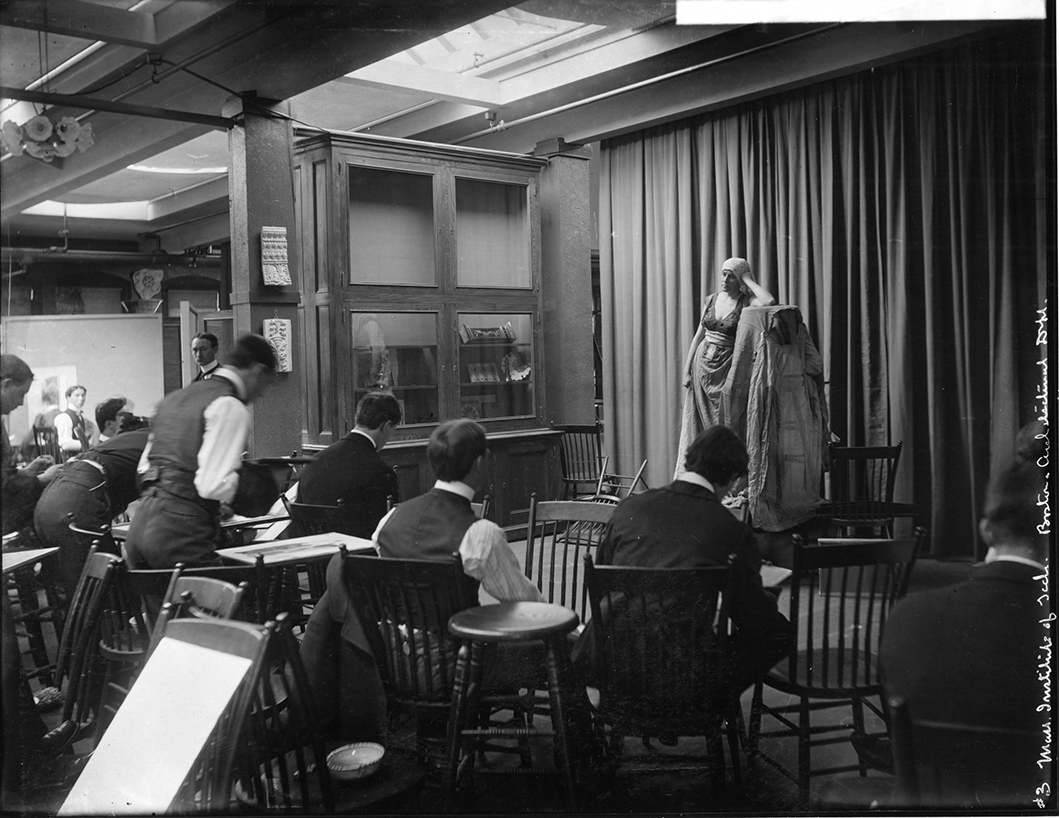

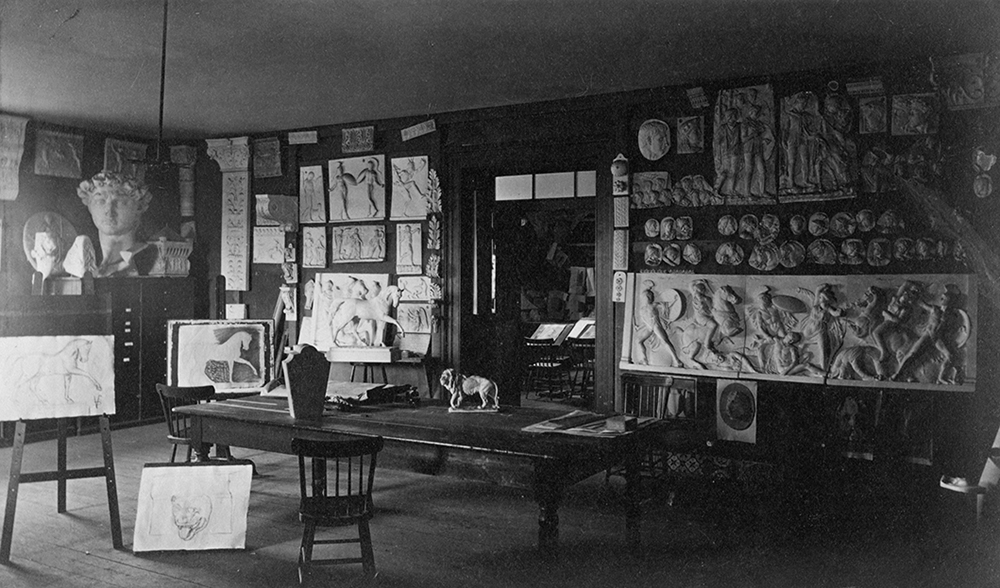

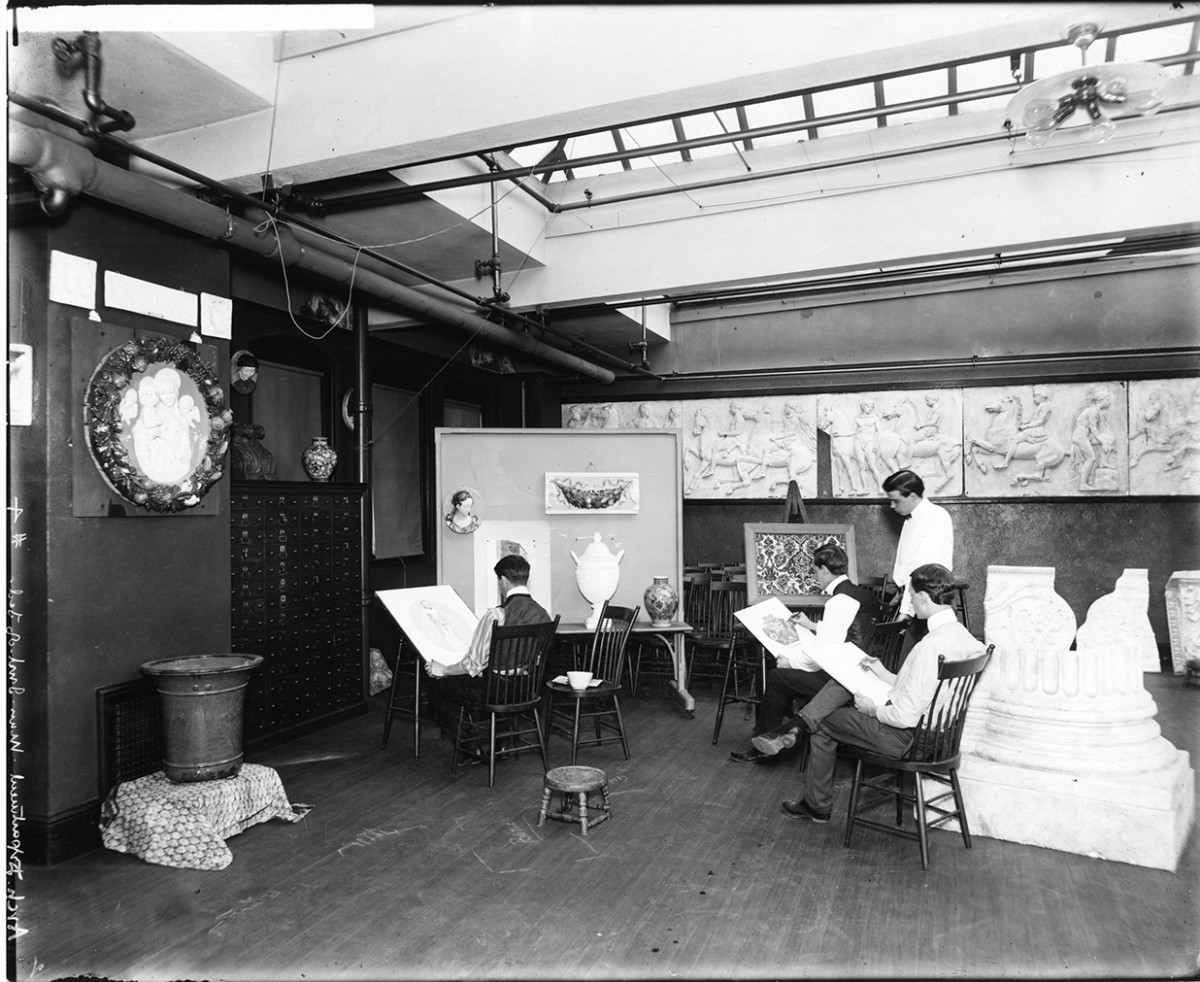

William Ware, the founder of the architecture program at MIT in 1866, insisted on a curriculum that incorporated not only the history of architecture and ornament, but also the entire realm of fine arts. Architecture students were expected to train rigorously in mechanical and freehand drawing, including instruction in “sketching in black and white and watercolor, and drawing both from the cast and from life.” To support this part of the architect’s training, the Institute, thanks in large part to Ware’s efforts, amassed an extensive collection of drawings and artifacts, which is described in the 1889 course catalogue:

“Several thousand photographs, prints, drawings, and casts have been collected for this department, by means of a special fund raised for the purpose. To these collections large additions have been made, mostly by gifts. Models and illustrations of architectural detail and materials are arranged in the rooms of the department. The chief part of the collection of casts of architectural sculpture and detail belonging to the department has been deposited in the Museum of Fine Arts, together with the architectural collections belonging to the Museum. The students of the department have free access to them at all times; and as the museum building is close at hand, no inconvenience results from the change. The space thus gained is filled with specimens of metal-work, tile-work, glass-work, and wood-work, partly purchased, but mostly deposited with the department by the manufacturers, forming a museum of sanitary and building appliances.”

With World War I came major changes to the Course in Architecture—a reduction in enrollment, an influx of new staff as many professors who had taught in the program since its founding retired or resigned, and the creation of new classes to keep pace with the technological developments of the day. Despite tumult, the department was resolute in its belief that, “Architecture is essentially a fine art, which for its inspiration must continually refer to the wonderful achievements of the past, and for its fulfilment must borrow much from the sciences and from engineering.” In the early decades of the twentieth century, drawing classes remained an integral part of the architecture curriculum, and students were still required to carefully study the historic drawings and artifacts assembled in the drawing-rooms and at the MFA. These skills prepared students to work in architectural offices typically run by Ecole des Beaux-Arts graduates and aligned with the neoclassic trend ushered in by the 1893 World’s Fair.

Francis Chandler, who retired as head of the Department in 1911, had established a program of study grounded in the understanding and use of historic precedent that continued under the leadership of his successors, Desire Despradelle (1911-12), James Knox Taylor (1912-14) and William H. Lawrence (1914-19). The 1916-17 course catalog states, “The education of the architect, therefore, which is based primarily upon the canons of art, must at the same time include historical study of civilization, painting, sculpture, and architecture, as well as some instruction in science and its engineering applications.” Freehand drawing began in the first year and continued throughout the program, with exercises that progressed from drawing details of casts to decorative figure designs. Courses were offered in watercolor, pen & pencil; composition & rendering; clay modeling; and shades and shadows. Additionally, there were courses on the history of design & architecture, lectures on the orders, and a history of European civilization & art that aspired to survey the entire canon of painting and sculpture. Ralph Adams Cram, who was appointed senior Professor of Architecture in 1914 and department head from 1919-22, offered a class in the philosophy of architecture which focused on architecture’s ability to express various cultures.

Given the emphasis placed on architects’ “instruction and training in the fine arts” at MIT in the teens, it is not surprising that several graduates became well known for their artistic prowess, independent of contributions to the field of architecture. Samuel V. Chamberlain ’18 became an author, photographer and a preeminent etcher and lithographer. John Taylor Arms ’11 and Louis C. Rosenberg ’13 were also etchers of note. Arthur L. Guptill ’16 wrote art textbooks, and co-founded Watson-Guptill Publications, Inc.

As World War I ended, leaving many of Europe’s historic buildings in ruins, seven MIT architecture students, and four MIT engineers, joined the reconstruction efforts in the most devastated regions of France in 1922. Their foundation in drawing and knowledge of the historic styles doubtlessly served them well as they made measured drawings of the ruined structures and designed new edifices. In the twenties and thirties, new architectural styles and new materials and technologies increasingly influenced courses offered in architectural schools, and classic training waned. But William Emerson, who led the MIT Department of Architecture from 1919-39, was a former student of Ware and studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts himself. Even as he oversaw the architecture curriculum embrace the latest trends, he sought opportunities for students to travel to the storied sites of Europe to study Antiquity and conduct archaeological research. In 1938, before the end of Emerson’s term, the School of Architecture moved to its current location in the Cambridge campus group.