MIT students reimagine the architectural survey at an important site of African-American history

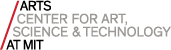

When Booker T. Washington arrived in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1881 to start a new land-grant university for Black students, he discovered that there was no federal money for either the land or the buildings. He eventually found an abandoned 100-acre plantation on the outskirts of town, and recruited Robert R. Taylor, an MIT graduate of the class of 1892 and the country’s first accredited Black architect, to design the school’s buildings and lead its architecture program. After constructing a kiln to make bricks, the students then literally built the school with their own hands.

Among the buildings Taylor designed are a cluster of brick buildings called the Wilcox Trade Buildings. Manual training, from carpentry to shoemaking, was an important part of a curriculum created to educate and teach self-reliance to rural Black communities in the years following emancipation, for what Washington envisioned as “freedom colonies.” The Wilcox buildings are among the last remaining structures built and maintained by Taylor and his students. While it is uncertain whether the bricks used for the Wilcox buildings were made by students, the campus’s older buildings were handmade with clay harvested from a nearby valley. At the height of construction, the students were producing an astonishing 60,000 bricks daily. But now, only two of the original buildings are still in use, while the others are in a state of disrepair.

In January 2024, a group of MIT architecture students traveled to Alabama to create the first official survey of one of the Wilcox buildings, using the standardized guidelines established by the Historic American Building Survey (HABS). Formed by the government in 1933 as part of the New Deal, HABS provides records of important buildings that are in danger of being lost. Through drawings, scaled architectural plans, large format photographs and written reports, this documentation, stored in the Library of Congress, helps preserve the country’s architectural heritage for future generations. “The Library’s holdings include more than 40,000 historic structures and sites across the United States. But, interestingly enough, if you go to the archive of the Library of Congress to search for any documentation on Tuskegee campus, there’s just not a whole lot, despite its designation a National Historic Site,” says Carrie Norman, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture at MIT.

As part of Norman’s course “Brick x Brick: Drawing a Particular Survey,” the students collected field notes and took measurements of the building using both traditional tools–measuring tape–and more recent technologies, such as a drone that took photos of the building every eight to ten feet to produce three-dimensional digital models.

But they also challenged the limitations of a traditional survey. “What you’ll find is that traditional surveys, like HABS, prioritize consensus surrounding geometries, materials and assemblies, but then other qualities like the socio-spatial context, the labor or the weathering are all absent,” says Norman, “In the class, we were really aiming to assess the ways in which this form of documentation is adequate and inadequate to describe how we see the building.” To better understand the larger context of the campus’s material culture, the students conducted research in the university archives and visited a small family-run brick plant that uses antique equipment, offering insights into the methods and labor involved in historic brick production.

While a survey, based on careful observation and measurement, is considered a “neutral or even objective form of drawing,” says Norman, it still reflects our own ingrained biases about what kinds of information we deem important or not. “The class was invested in teasing out these biases,” she says, “And when you observe a building through the act of drawing, you might reflect on other aspects of the building that wouldn’t have been captured in a traditional survey. It might start to tell another story.”

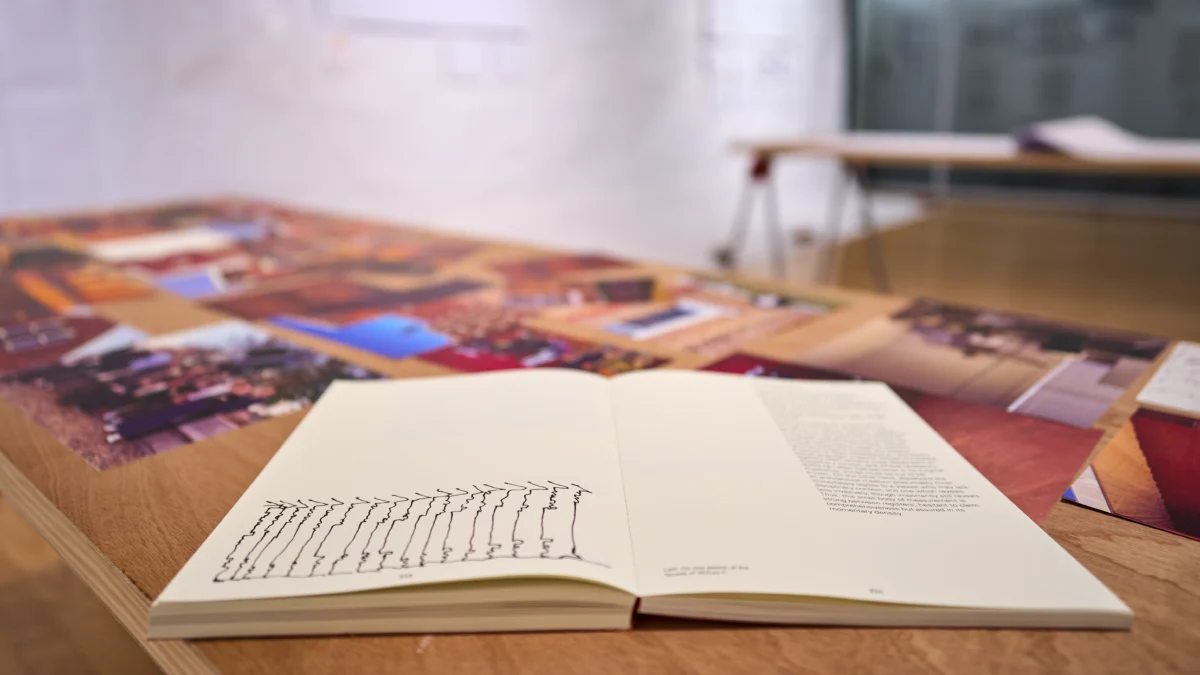

The resulting surveys, now on view in the exhibit BRICK X BRICK: Drawing a Particular Survey at the MIT Wiesner Student Art Gallery and documented in an accompanying book, are loving studies of surfaces, with careful attention to the patterns and colors of brick, as well as the cracks and lichen coverings. In these works, the students are as much archeologists as architects, as they attempt to uncover traces of the past. In one project, a student meticulously drew all of the fingerprints imprinted in a sample of the bricks observed. In many of the surveys, we see a recognition of the human hand, reflecting how, for Tuskegee’s early students, the building of buildings was a practice of freedom. The HABS survey, conducted at the beginning of the course will be added to the archives of the Library of Congress, and the research will continue with a new cohort of students beginning in February 2025.

The architectural drawing, as a sketch or a plan that illustrates a future building, is a speculative form. The survey, on the other hand, could be considered its opposite: a record of a history that is already over. But the power of this work is that it rewrites the survey as its own document of the future. The survey is no longer a “conveyor of facts” as Norman writes in the book’s introduction, but an “instrument of stories.” The surveys show how the past can be shaped for new purposes by new ways of seeing, containing within it the possibilities for many possible worlds.

This project is supported by the MIT Department of Architecture, The Council for the Arts at MIT, The Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture and Construction Science, and the Tuskegee University Archives. Exhibitions in the Wiesner Gallery are curated by Sarah Hirzel.

BRICK X BRICK is on view at the Wiesner Gallery in MIT building W20 through December 19, 2024.

Written by Anya Ventura

Editorial direction by Leah Talatinian