Graduate students and alumni discuss their work at the Council’s Annual Meeting

The history and vibrant potential of artistic research at MIT dates back to 1967, when György Kepes founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS). “In artistic research, research questions derive from the artistic practice of the artist-researcher,” explained Andrea Volpe, director the Council for the Arts at MIT, speaking at the Council’s Annual Meeting. “Research methods such as archival research, ethnography, and various forms of documentation are integral to the artists’ practice and use of materials. The research in many cases becomes an artistic material.”

On May 7, 2021, Joel Austin Cunningham, SMArchS ‘22 and Kwan “Queenie” Li, SMACT ‘22, Manar Moursi, PhD student in History, Theory and Criticism and the Aga Khan Program in Islamic Architecture, and Nancy Valladares, SMACT ’20 discussed the role of artistic research in their work with Wiesner Student Art Gallery Coordinator Sarah Hirzel and CAMIT Grants Committee Vice Chair Sheila Lemke.

Advancing graduate student artistic practices

Recently, and with the help of a CAMIT grant, Cunningham and Li transformed their video installation, Nature, Data, Weeds, for the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale so it could be presented both online and as an installation at the Hong Kong Pavilion. Researching and mapping the rise of data urbanism, in which data centers are increasingly built into cities around the globe and housed in buildings that either mimic or replace residential urban architecture, was foundational to their artist inquiry. Their guiding question, Li explained, was “What does it mean when you walk past a street next to your home and suddenly discover weird buildings that are swarmed with CCTV cameras, have no windows, and always have a very mysterious humming sound?” Rather than present their research in a more traditional scholarly format, the artist-architect duo turned to video to create “an immersive, holistic experience” that could “address the emotional aspects brought by all these secret arrivals of data centers in our neighborhood.”

Moursi’s work as an artist-researcher spans two disciplinary homes. As a historian and scholar of Islamic architecture, she studies the material and physical significance of new mosque architecture, which she also addresses through her artistic practice in video, installation, and print. With support from CAMIT, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Alserkal Arts Foundation, Moursi is expanding her ongoing multi-disciplinary project The Loudspeaker and the Tower, to include an artist’s book that explores the development of Cairo’s new mosque architecture, and the ways in which piety and benefit are mixed in contemporary Egypt to yield new architectural and urban forms. “The artist’s book has its own sort of architecture, or is its own artistic object that is more accessible, and that I can use to share the knowledge or the archive of materials I assemble in the process underlying both my scholarly and artistic work,” she explained.

Retelling agricultural and botanical histories

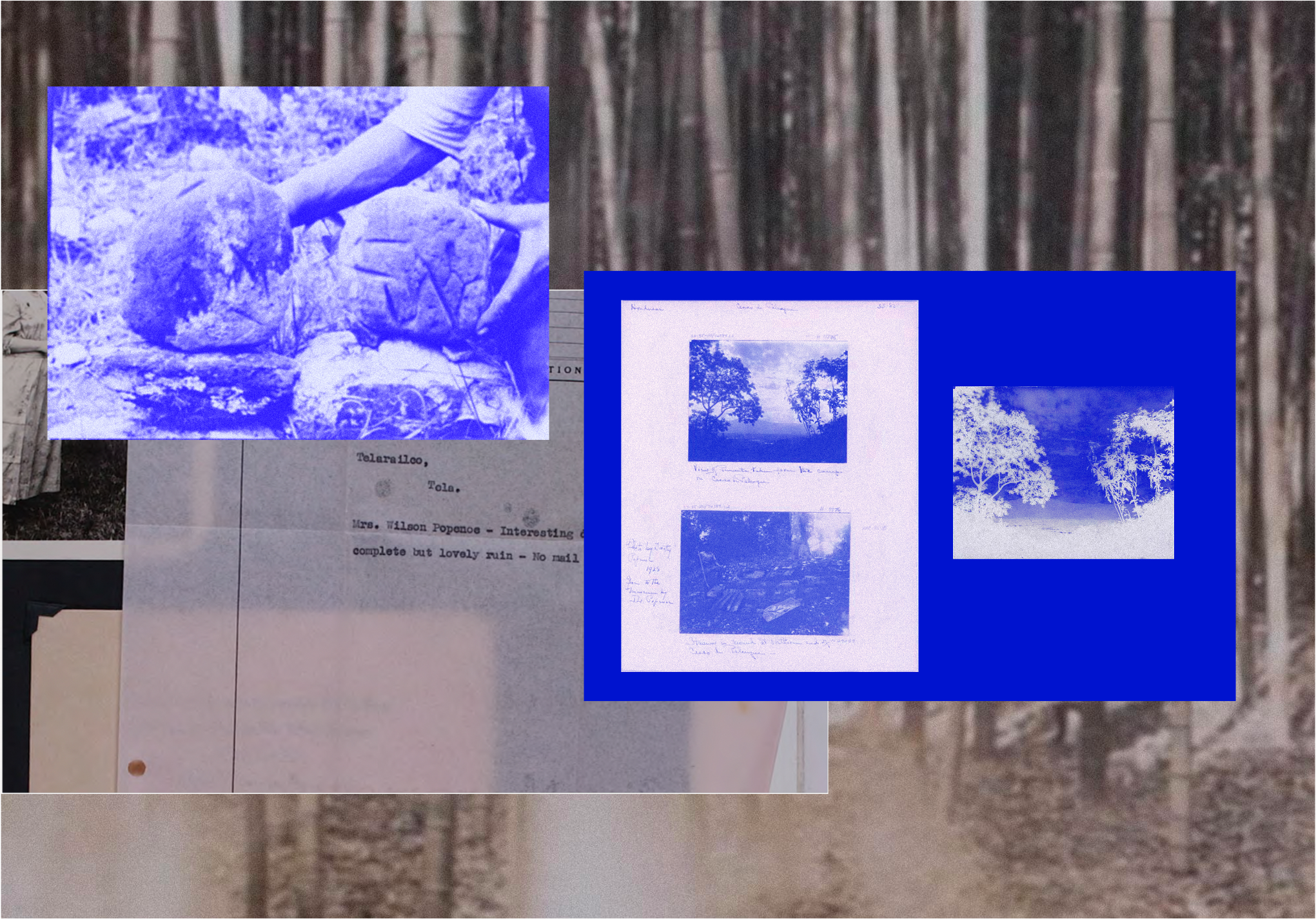

Valladares’ exploration of archival materials infuses her installation, Botanical Ghosts, which she describes as “retelling the agricultural and botanical histories of my home country of Honduras through writing and archival reconfigurations.”

Drawing from archival materials documenting the work of British botanist Dorothy Popenoe at the Lancetilla Botanical Experimental Station, Valladares made a film and created an array of fictionalized correspondence that she displays side-by-side with historical records and photographs. The resulting installation recontextualizes Popenoe’s forgotten story, reframing the colonial scientific narrative from a critical, artistic perspective. Botanical Ghosts “came to life digitally” with support from CAMIT. Valladares’ virtual exhibition is presented by the MIT Wiesner Student Art Gallery, which hosted a virtual opening and a cross-disciplinary conversation on ecology, history, and memory last spring.

Only at MIT

For these artists the opportunity to advance research-based artistic practices is inseparable from new collaborations and cross-disciplinary conversations that are unique to MIT.

“I’m thinking more rigorously and expansively,” Moursi said. Describing MIT’s role in the development of her scholarly and artistic practices she says, “technology and science weren’t infused in my practice before, and now I think more and more about them.” At MIT she has gained access to different tools and methods that come from seeing how people work and develop their projects and ideas.

Cunningham echoed this view. “Coming to MIT, not only are we able to access the professors and researchers making new discoveries or provocations, but also the informal conversations we’re able to have within the architecture and design community give a hint at what’s happening and what changes people are expecting to see over the coming years.”

Valladares credited MIT for providing an environment in which her artistic practice could evolve and described her graduate experience as uniquely collaborative and immersive: “It is a non-stop process, particularly in ACT where there was a co-evolution and growth that was happening, mutually, at all times,” she observed. “My practice would not be where it is were it not for my colleagues and for the conversations that I’m able to have with people either adjacent to my field or completely outside of it.”

Making space for research as art practice

Even as their artistic practices range widely, integrating research and artistic practice plays a crucial role in the development of the work of these artists, designers, and thinkers.

“While engaging in the research, particularly in the archives,” Valladares explained, “I often notice that narratives form in the empty spaces, or in the things that we’re missing, and it’s in those gray areas where I feel artistic research can thrive and flourish. I think entire worlds can be created in those areas of strangeness,” a process of exploration and creation she has continued this year as a fellow at Harvard’s Film Studies Center.

The research process functions in a similarly illuminating way for Cunningham and Li. “This process of artistic research,” Cunningham explained, “helps us to understand the context of the work, but it’s also the moment that we identify overlaps between our own practices—we see where my architectural interests overlap with Queenie’s artistic interests—these moments are where we identify where we can add something new by working together.”

For Moursi, working with architectural research, particularly photography and participant-observer interviews, both informs and provides a crucial counterweight to her work as an architectural historian. “My artistic process is crucial to helping me work through my scholarly work in a different way,” she explained, “I couldn’t do one without the other.”

The Council for the Arts at MIT (CAMIT) is a group of alumni and friends with a strong commitment to the arts and serving the MIT community.