An exhibition at the Wiesner Student Art Gallery invites visitors to contemplate the intelligence embedded in living systems

“When we attune ourselves to the multiple intelligences of nature, we recognize that the technology is already there. It’s just about a willingness to pay attention.” As a graduate student in the Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT) program at MIT, Alejandro Medina has identified a simple formula for a lifetime’s work. The task is to attend, to attune, and to create.

The conundrum is how to shape the conditions that allow for that sustained attention. Reconfiguración, an exhibition of five new works produced by Medina during his first year of graduate study, carefully arranges the space of the Wiesner Student Art Gallery into a training ground for perception and imagination. While the title of the exhibition refers to the central work in the exhibition—a series of mobiles composed of fallen branches sourced from the MIT campus—it might equally refer to the synaptic repatterning that occurs when we are compelled to slow down, tune in, and observe what emerges. The exhibition encompasses media including sculpture, drawing, video, and immersive sound, and although the mood might be meditative, the stakes are high. Medina’s guiding preoccupation is the presence and threat of climate change; his work is motivated by the urgent need to rethink relationships between nature, technology, and science, making way for new paradigms of resilience and innovation.

Meditation and imagination

“The experience of walking between and around the mobiles is comparable to the making process itself,” said Medina. “When constructing the mobiles, I would try to break away from the structural logic and growth patterns of the branches—exploring the new formal languages that could emerge from their reconfiguration. All components in a mobile are in correspondence, so there is no way of fully predicting what the final form will be. I would start with one branch, and the relationships would shift in an entirely new direction as soon as I added a second branch or weight. I found myself engaged in a type of meditative dance with a system, producing unexpected configurations as I sought to achieve the balance of a final composition.”

Medina originally trained as an architect, and he views his artworks as models for potential forms as much as standalone objects. Among his influences, he cites the pre-computational methods for structural optimization developed by the architect Antoni Gaudí, and the botanist Francis Hallé’s study of the branching patterns of different tree species. “At architecture school, I found myself growing increasingly resistant to computational thinking,” he explained. “I wanted to work with my hands, to have direct contact with materials. All the same, the rigor and technological training of an architectural education has defined how I approach my art practice—I like to think of the artist as a type of scientist, with each work being a hypothesis put out into the world, ready to be tested.”

Productive disruption

Medina combines theories of computation with hands-on making, applying both digital and analog techniques in a constant interchange between different spatial dimensions. He has exhibited his art internationally and participated in prestigious residencies; through ACT, Medina now has the opportunity to fully integrate his role as an artist, scholar, and architect. “The program is quite unique,” he says. “As a small group of artists within an institution dedicated to technology and innovation, we have the freedom to move across departments, forming meaningful mutual relationships with so many incredible minds. I wouldn’t go as far as to say we’re trouble-makers—but perhaps we do serve to destabilize things a little, prompting new approaches to problem-solving. That’s the power and potential of involving artists at a place like MIT—the possibility of envisioning the prospective worlds in which these new technologies can exist.”

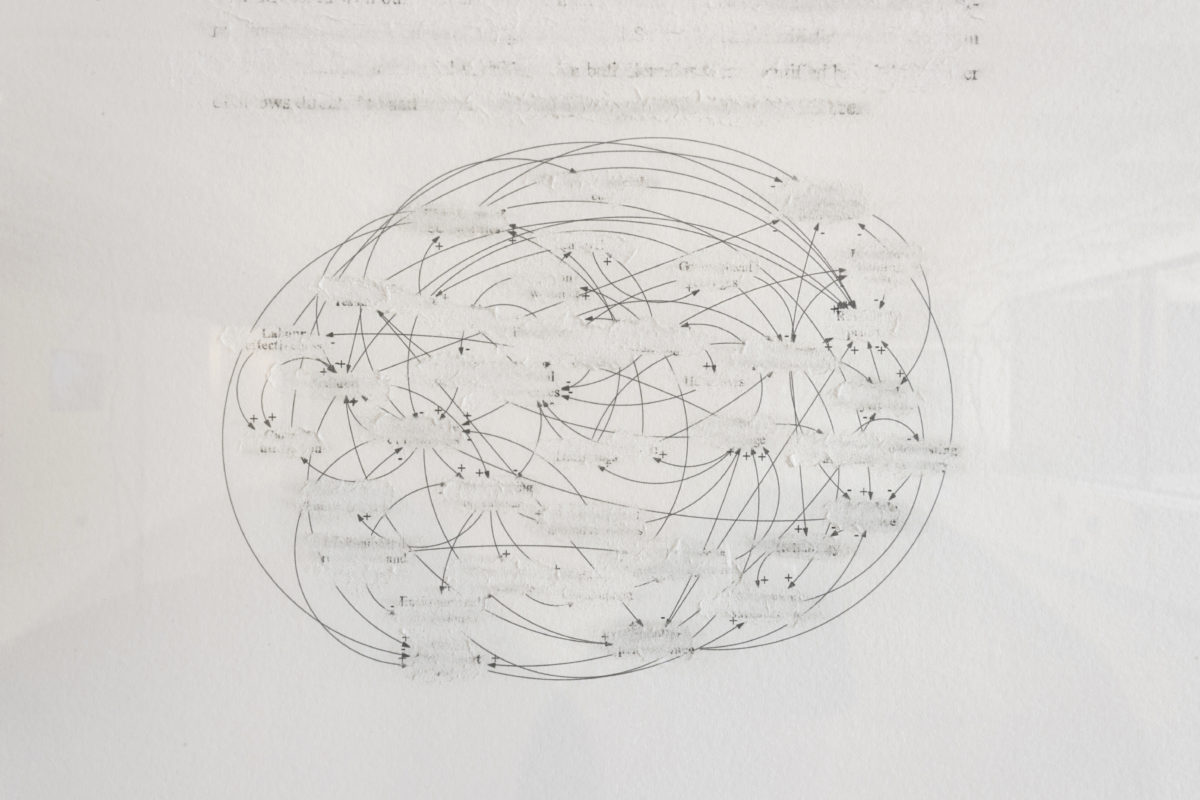

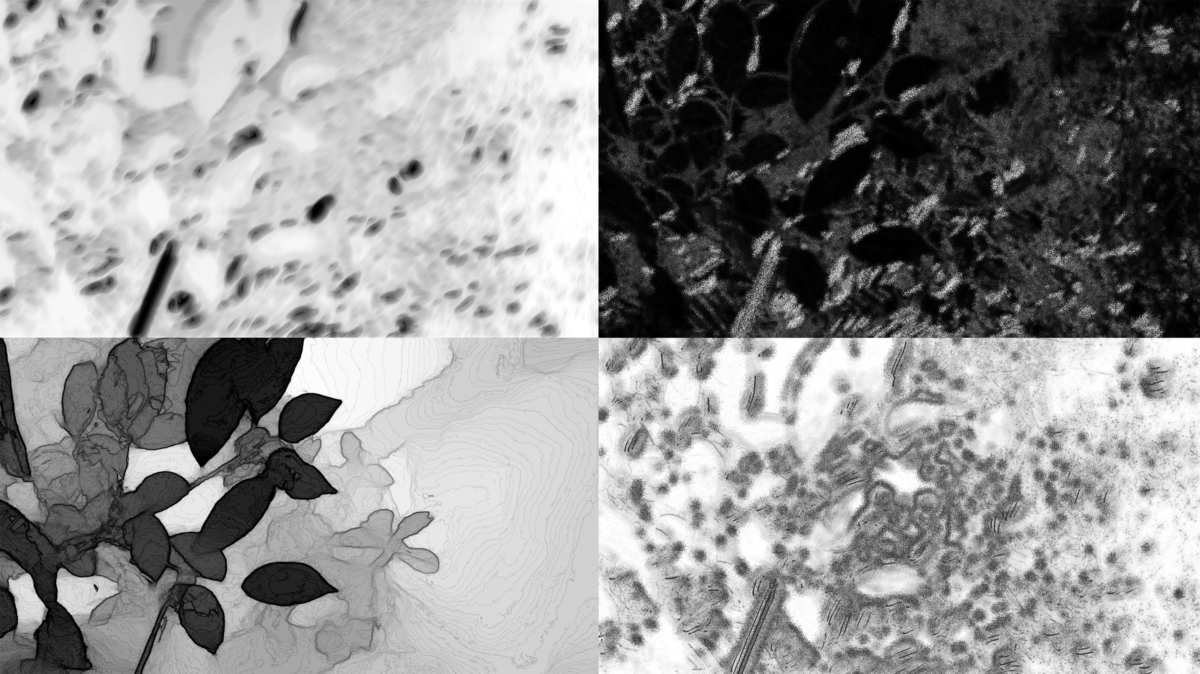

Together, the works in the show generate a multi-sensory environment to allow different material and structural intelligences to emerge. Cloud Forest (Ways of Seeing) (2021-22) is a three-channel video combining computer vision filtering techniques with slow-motion footage of a cloud forest in Guatemala, implying a continuity between artificial intelligence and the cohabiting life forms of a biodiverse ecosystem. The gallery space is permeated by an immersive sound recording, Cloud (2021), cross-referencing the audio-atmosphere of the forest with recordings of the overheating computers that constitute the physical infrastructure of “the cloud.” Untitled (Study for a Mural) (2022) recycles paper waste from the MIT Media Lab facilities, using tree branches as drawing tools to form a 20 ft mural of modular patterns. Figures (2022) is a series of drawings applying techniques of erasure to specific pages from influential academic papers about climate change. With all traces of legible language removed, the information is abstracted to the visualizations and models that have shaped public understanding of the climate crisis—an understanding which is likewise produced through multiple levels of abstraction.

Complexity and opportunity

Each work in the show indicates the unpredictable workings of complex systems—whether the rapid extrapolations of machine learning, or the fluctuations and feedback loops of interdependent ecologies. For Medina, the impossibility of full understanding gives rise to wonder—a feeling he recalls from early encounters with the natural world. “When I was around ten years old, my family moved to a new housing development which was in the process of being built in an old-growth rainforest just outside Guatemala City,” he explains. “I ended up spending long periods of formative time in the forest, and I had to watch as trees were cut down to make space for the development. At the end of each day, following the sound of chainsaws, I would approach these trees as they were loaded onto trucks. Their branches—which might have previously been 50 to 100 feet up in the air—would be densely covered with epiphytes: a rich ecosystem of orchids, air plants, philodendrons, and bromeliads that I had not encountered before. To me all of nature is an expression of imagination, but encountering these species made that imagination wildly apparent from an early age.”

Medina started taking home certain plants with the goal of saving them—before long, the house and the garden were full of thousands of different botanical species. The phenomenon gave him a taste of what it felt like to take agency; to bear witness to the presence of living systems and to explore opportunities for new and generative reconfigurations. “If someone can enter the gallery space and recognize the evolutionary intelligence embedded within something as seemingly simple as a single branch—that’s enough for me,” said Medina. “In many ways, the exhibition is about how we model relationships to try and understand the world around us. A subtle change in that understanding can be a starting point for real and necessary change.”

Article by Matilda Bathurst

Editorial Direction by Leah Talatinian, Arts at MIT

Established as a gift from the MIT Class of 1983, the Wiesner Gallery honors the former president of MIT, Jerome Wiesner, for his support of the arts at the Institute. The gallery was fully renovated in fall 2016, thanks in part to the generosity of Harold (’44) and Arlene Schnitzer and the Council for the Arts at MIT, and now also serves as a central meeting space for MIT Student Arts Programming including the START Studio, Creative Arts Competition, Student Arts Advisory Board, and Arts Scholars.

Reconfiguración

Wiesner Student Art Gallery

MIT Building W20, 2nd floor

Exhibition dates: September 9–October 29