Visit the online exhibition of work by the 2020 recipients of the Harold and Arlene Schnitzer Prize in the Visual Arts.

Students Plumb Barriers of Sound, Space, and Sight at MIT

Each year, the Harold and Arlene Schnitzer Prize highlights student work in the visual arts at MIT. Portfolios span almost every imaginable medium and theme; many, if not most student artists bridge diverse disciplines and departments, drawing on MIT’s broad knowledge base and its culture of collaboration.

Students submit a body of work for the competition, which culminates in a gallery show. This year’s show is presented virtually in an online exhibition. “The work of this tremendously talented group of students embodies the broad range of artistic pursuits taking place at the highest levels of excellence at MIT—theater, music performance and composition, and design among them,” says Andrea Volpe, Director of the Council of the Arts at MIT (CAMIT.) “Their work also demonstrates the ways in which technology and computation are themselves artistic materials essential to multidisciplinary arts-making across the Institute.”

This year’s three winners all test limits with their art. Five-thousand-dollar First Prize winner Nicole L’Huillier, a third-year PhD student in Media Arts and Sciences, stages real-time sound installations to trace the border between living and inanimate spaces. Second Prize winner Rae Yuping Hsu, who graduated this year from the MIT Program in Art, Culture, and Technology, uses fermenting bacteria to probe the permeable membrane that separates microbes from humans. And Jonathan Zong, a PhD student in Human-Computer Interaction at the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and who took third place, uses graphic design to sketch the shifting frontier between the natural and machine generated worlds in which we live.

Place as Protagonist

There’s no such thing as an inanimate object for Nicole L’Huillier. “Every material body in the universe is resonating to some frequency,” says the Chilean born and trained architect, who came to MIT to bridge her passions for design, music, and art. “Organic and inorganic objects share these frequencies. They connect the human and the non-human.”

L’Huillier first explored the concept of animated spaces in “Spaces That Perform Themselves,” the performance piece that was her master’s thesis at MIT. In that piece, a human performer stood beneath a suspended six-by-six foot cube. Motors inside the cube shifted its textile interior on cue, changing its shape and texture. “That project spurred my thinking of space not just as something that contained performance, but was the performance,” says L’Huillier. “And I began to ask why we perceive space as lifeless when in fact it’s animated.”

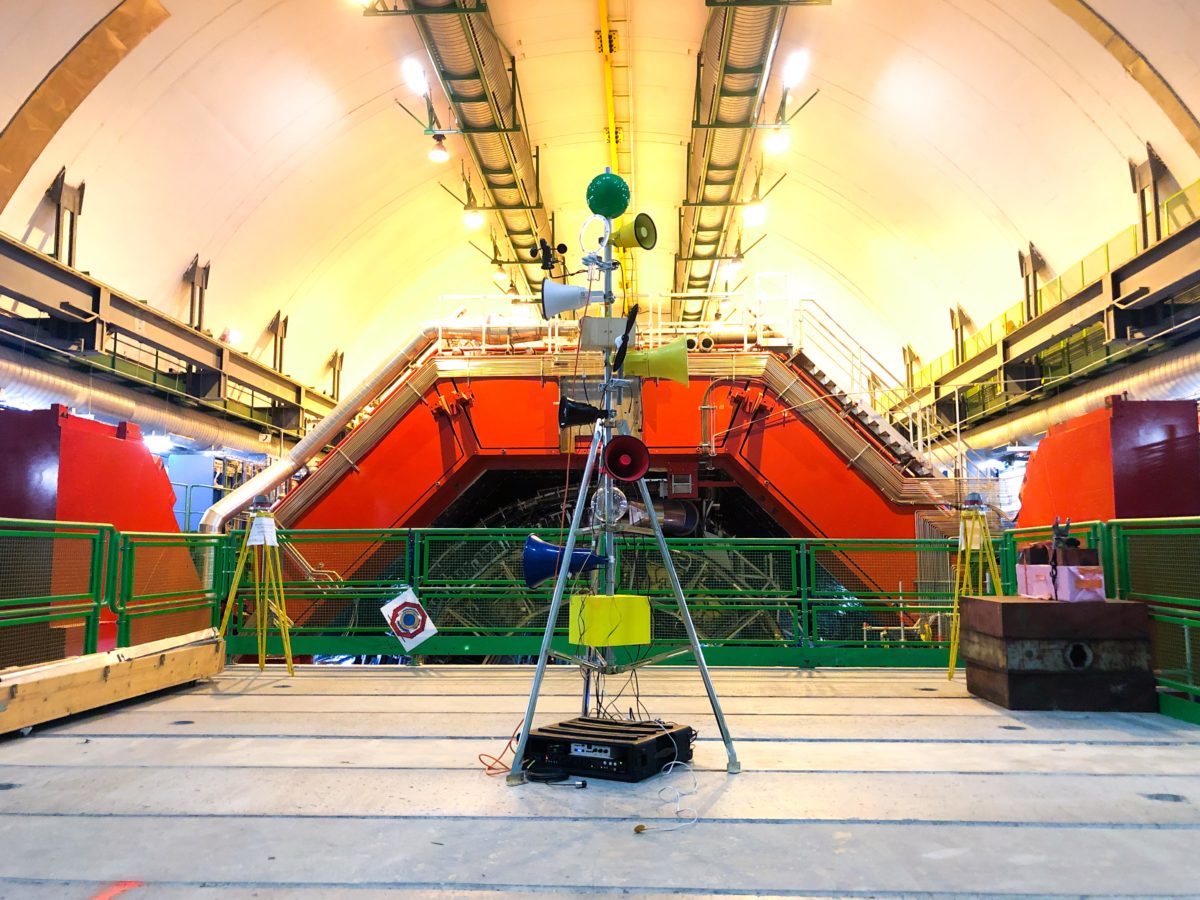

Space is decidedly the performance in L’Huillier’s Schnitzer Prize portfolio. The winning project consists of a series of sound sculpture installations titled “El Poema de la Fabrica Cosmica” (“The Poem of the Cosmic Factory.”) During her project, the artist set a sculpture equipped with listening devices and environmental sensors 80 meters below the earth’s surface at the CERN particle accelerator in Geneva, Switzerland, and 3,000 feet above sea level at astronomical observatories in Chile’s Atacama desert. The sculpture, which she calls “PARANCANTORA,” gathers ambient sound while its sensors collect environmental data including shifts in temperature, electromagnetic fields, and atmospheric pressure. All inputs are transformed into sound and broadcast through the device speakers in real time.

“Working with physicists and astronomers has helped me understand a few of the universe’s many mysteries,” says the former rock drummer. “The research is empirical and rigorous. But the art is experiential. Sound is the best way for a space to express its narrative.”

View the work of Nicole L’Huillier

In Constant Ferment

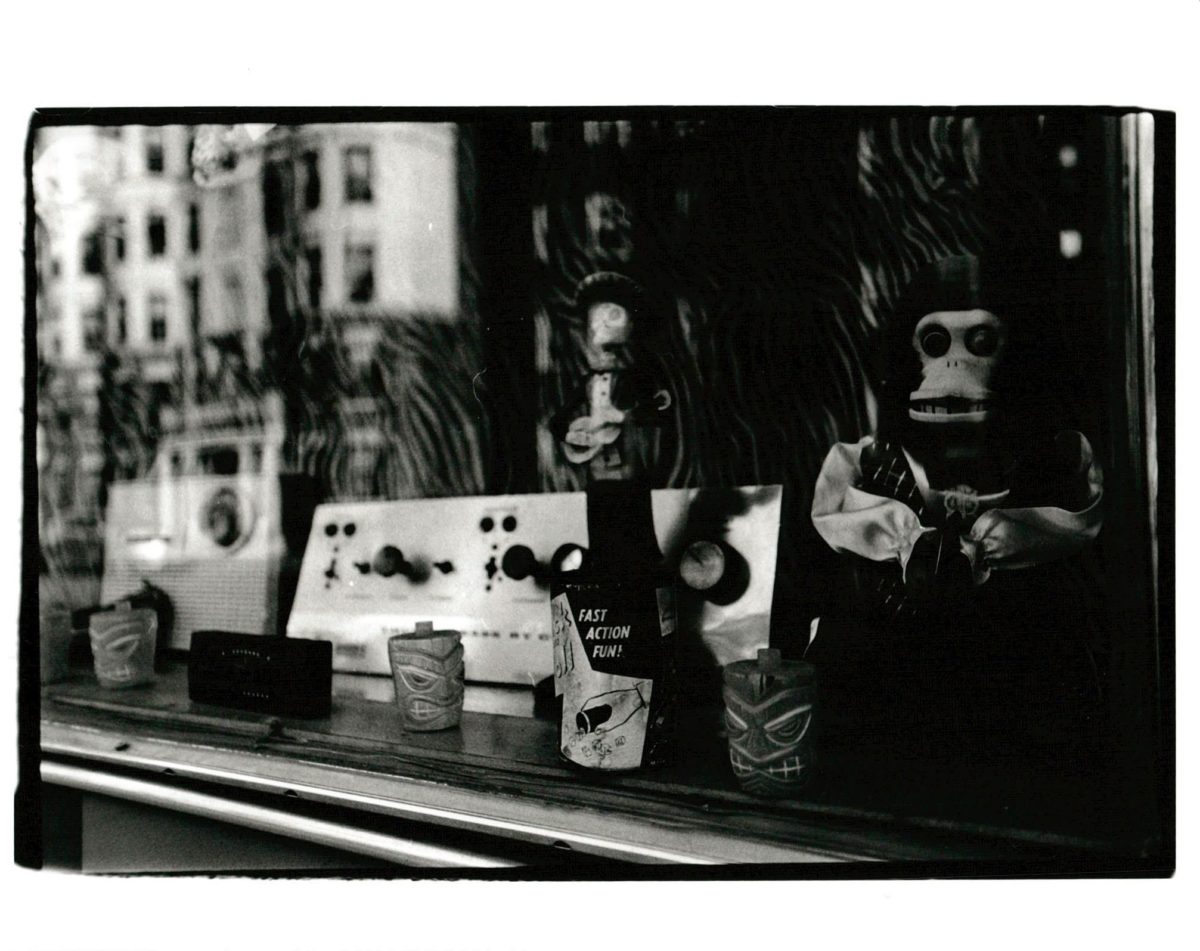

Born and raised in Taiwan, Rae Yuping Hsu, Masters of Science in Art, Culture, and Technology (SMACT) ’20 originally studied to be an occupational therapist. Her first forays into art were photography, and later glass sculpture, including a collection of glass artificial limbs. But her focus shifted dramatically after an artist’s residency in Perth, Australia, where she discovered and dove headlong into biology, bacteria, and the process of fermentation.

“Everything in those processes is fascinating,” says Yuping Hsu, who also holds an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD.) “The bubbling. The colors. The first layer of flesh that forms. There are so many metaphors to be expressed in it, the impulse for containment, and the fear of contamination.”

Yuping Hsu’s recent body of work uses the language of biology and biotechnology to probe the distinctions and similarities between human and microbial life. Her installations and sculptures percolate—gelatinous, semi-opaque surfaces that evoke the distant origins of life on earth and question the efficacy and ethics of contemporary science. “Her work points to a desire to embrace our biological complexity and entanglement,” says Gedminas Urbonas, Associate Professor and Hsu’s thesis advisor. “It creates exchanges between humans and microbes to question when one self can become another.”

View the work of Rae Yuping Hsu

We Are Being Watched

For Jonathan Zong, science and art are complementary methods he uses to chart the shifting tides of the natural and digital worlds in which we live. “There is a fundamental tension between the chaos of human existence and the algorithmic frame we attempt to put around it,” says the Human-Computer Interaction PhD student—and Soros New American Fellow—who first took an interest in art with a course in graphic design as an undergraduate at Princeton. “I acknowledge there are benefits to the algorithmic frame. It’s just that there’s a risk people will mistake that abstraction for the real thing.”

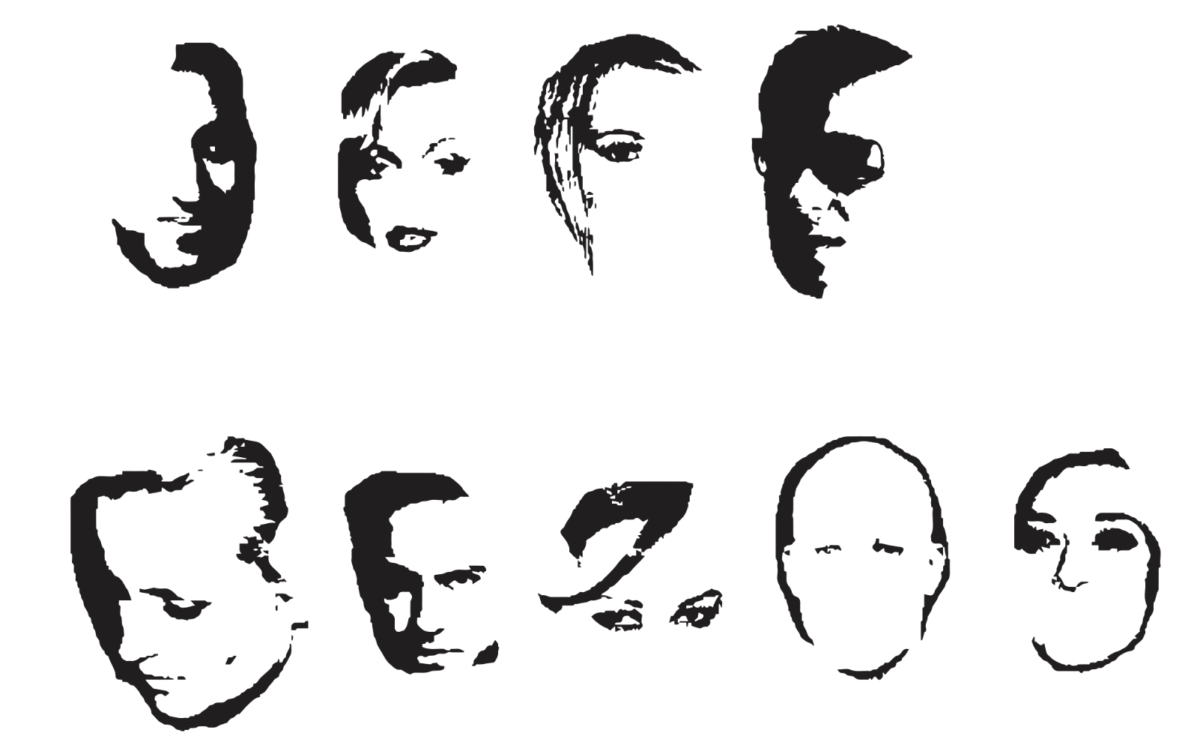

Zong’s body of work includes standard graphics, an assembly of 12-inch-high decals that spell out the name “Jeff Bezos,” and “Biometric Sans,” an interactive typing exercise where letters change size and form according to the typist’s speed. “Art operates on a cultural level, generating metaphors and symbols,” says Zong, who is creating the interactive web interface for the Schnitzer Prize virtual gallery. “It can help people identify implicit assumptions they’ve never questioned, such as, in this case, that typing makes everyone look the same.”

View the work of Jonathan Zong

—

Written by Ken Shulman

The Council for the Arts at MIT presents several awards annually to MIT students who have demonstrated excellence in the arts.