A couple familiar red and white bags from the COOP bursting with MIT textbooks sat in a corner of the green room while legendary audio engineer and DJ, Gimel “Young Guru” Keaton, talked to the press before his recent lecture at MIT. Guru’s book store purchases spoke volumes about his enthusiasm for visiting the Institute. “Since I was a child this place has been like the Holy Grail of engineering and design. I used to try – it’s a lot easier now with the internet – to get my hands on as much stuff from here as possible – technical papers and such. This is to me one of the places that has consistently throughout history produced some of the best people, and that’s not by accident,” he acknowledged.

Young Guru toured every corner of campus that he could during his brief visit. And with his Leica in hand, he captured a lot of MIT’s public art, architecture, and overall ambience. Guru said, “Just coming here today, the physical aesthetic of the place matches what you would think of for people who are concerned with design and not just how the campus looks to the outside world. The design of this place looks like somewhere where people are getting to the nitty gritty of making things.”

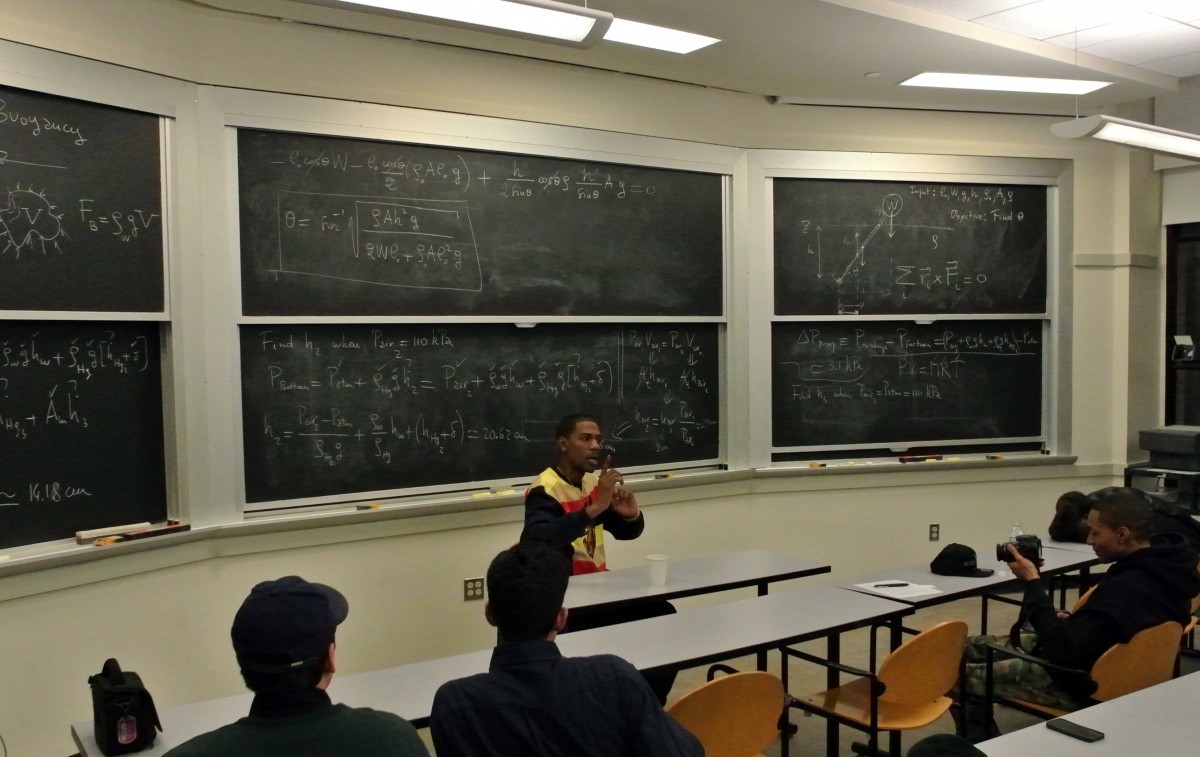

Young Guru, one of the men behind the iconic sound of world-renowned artist Jay-Z, presented the first lecture in MIT’s new “Hip Hop Speaker Series”, which continues with additional talks scheduled for April and May.

The series is presented by the Arts at MIT and TapTape, an MIT-based music startup (winner of the MIT Creative Arts Competition in 2014), and brings together eminent hip hop artists with leading faculty and students at MIT.

Cultural anthropologist Ian Condry (Professor, Comparative Media Studies, Writing, MIT) moderated Guru’s talk, “Design and Destruction,” and the conversation ranged from the seismic technological shifts in the recording industry in recent decades to myriad social issues, such as celebrity culture, artist as brand, positive role models in hip hop and changing consumer habits.

Below is an excerpt from the evening’s conversation with a selection of questions asked by Professor Condry, students and other audience members.

Can you describe when music went from being a hobby to something you wanted to do professionally?

There were sort of two stages. I have really incredible parents. I don’t know that thing where people say, “I hate my parents. I want to get away from my parents.” I worshipped my mother and my father. I still do to this day. When I decided not to play basketball – which everyone thought I was going to do – I made that conscious decision at the kitchen table with my father that I was instead going to pursue music. My father said, “Follow your dream.” That was one stage, but on that Fugees’ Tour is when the light clicked.

Before that time, my life was from New York City to Washington, DC. My mother’s from North New Jersey and my father is from Washington, DC, so that was my whole world up until that moment. Then, I’m in Russia, or Italy, and all these other places off hip hop music. It was shocking to me. I didn’t think that people outside the United States, or my little area, listened to this music. So, that was the moment it clicked, and I thought this could really be a profession.

The first couple shows I was nervous. This is the Fugees’ Ready or Not tour. You’re thrown on stage in a football stadium in front of 70,000 people. It’s amazing and when the nervousness leaves, you see, ok, I am good at this and I can do this.

Talk to me a bit about your different activities, practices and rules in music. You DJ, you produce and sound engineer, which is a word we all hear, but a lot of us have a vague understanding of exactly the role of a sound engineer.

It’s good you asked that question because a lot of people get it confused. A sound engineer is really supposed to just run the session. He’s the guy that knows how to work all the equipment, and this is pre-recording in the computer. I’m sitting at a big SSL desk, you have to know how to work the tape machines, you have to know how all the equipment behind you in the racks works, but most engineers were very quiet reserved people that just pushed buttons and facilitated the actual recording or mixing of the record.

I had made records with friends all through high school and college, and I was sort of doing this dual A&R (Artists & Repertoire) and engineering role where I was recording the music, but if you said this wack verse, I was going to stop you and tell you that “it is corny and let’s figure out the best way to make a record.” That’s one of the things that got me a little bit further with Memphis Bleek: The very first day we recorded, I stopped him and told him, “your verse is wack.”

I’m sort of the guy that would help people making music find a direction, how to edit their words and put them together in a better way. No engineer really did that, and I think that’s what stood out the most. That’s where my job blurred from engineering to A&R. So it sort of overlaps, and a beautiful thing happened when Jay asked me to come work for him, and we created Baseline Studios.

Imogen Heap made a tool awhile back with the MIT Media Lab, which is a glove that allows you to interact with the music you are producing, If you had a roomful of MIT students, is there a tool that you’d be interested in developing?

I would like to see 360 degree sound perfected. There are some things out there that come really close, but just directional hearing because we are very trapped into listening to sound on one place. Like something that would tell me that the plane is above me and it’s to my right and I have that natural directional sound or me knowing where you are in the room with my eyes closed just from hearing you, I’d like to see that perfected. Where we’re going with virtual reality and video games, we can direct people’s eyes, but the sound needs to catch up to the visual components.

As a director of multimedia, how do I focus people’s attention and sound could be another thing. In the existing left and right ear buds, because that’s how human beings hear. We shouldn’t need to be in a room with 80,000 speakers. That’s the thing that’s frustrating Hollywood, and once it gets done in the movie space, the sky’s the limit.

Out of the different things we’ve seen come out of the music industry, what do you think are the key principles — whether it’s label structures, or any aspect of the industry — that will survive into an uncertain future?

To understand, performance is back to being a performing musician. The majority of your money will come from performing and things outside the actual music itself, which is horrible, but it’s the reality of where we are today.

I like touring, but the question is whether it’s sustainable. When you’re 18, it’s cool to be in the back of a van and travel around and eat with your fans, but can a 45-year-old musician with an 18-year-old kid sustain himself like that?

When I first got into the music business, the album was the center of the universe. Everything was about the album. I spent a million to make an album, and then at least another $300,000 promoting the album. Busta Rhymes probably spent at times $2 million to make a video; that was a promotional item. Then, I’d beg MTV or VH1 to play my video; I didn’t get paid for the video itself, it was promotion. The more eyes on it, the more people who would buy my album. You went on tour, but tour was called “tour support.” It supported the album.

We’ve removed the CD from the center of the circle, and put the artist at the center, as the brand. It was slowly but surely done, but people showed you how to make money outside the music business. Your brand is sometimes way more important than just your music. Your music is important because it brings people to you initially, and without the music no one is going to care.

Fifty made $150 million off selling water in one year – way more than he made off selling albums. The water deal was only there because of the albums, but that’s the real deal. It’s about you becoming a brand, so that you can do what you want to do based on your popularity. It’s a sad state of affairs, but until we fix it, that’s the way it is.

I feel like the dream of the fans is that if there were a way to cut out the middleman, we could support you more directly. How can we best do that?

There are plenty of people making independent music, but where are their fans? I have a nineteen year old, a fifteen year old and two eleven year olds. My 19-year-old asked me when she was thirteen, why do they even still make cds? She’s conscious of the waste of plastic, and the earth doesn’t need that. She was on that kick.

My 11-year-old has never asked for me to purchase anything – any type of music. All he does is go on youtube or spotify, and the concept of owning an album is foreign to him. There are no more record stores. But the teenagers now are so into retro that vinyl sales have gone up. They are into buying vinyl for the retro sake of it. But with new music, it’s ubiquitous, so even the songs my kids download, they’ll erase because it’s taking up too much space on their computer. It has no value to them.

So, there are places to buy independent music, it’s just hard to move everyone to those places.

From working with Jay-Z, what are some of the key things you’ve learned from him and what do you think sets him apart?

What sets him apart is honesty and truth. He constantly tells the truth and a lot of rappers lie. A lot of people lie. You heard drug dealer talk before, but not from this place of regret. He brought existentialism to the hustler mode. We had exaggerated ideas of what a hustler was. Jay brought the regret. Someone’s dying, I’m putting this girl on a plane strapping cocaine to her and she could possibly go to jail, my brother shot at me — so it’s a different reality that he shows. And as he grows, his music grows. You go from “Big Pimpin’” to seeing the maturation of Jay-Z, where he can write a song about his child being born or about what it feels like to get married. There’s always a truth involved in it, that it is where he is at a given time.

Not everyone in the population is a drug dealer, so tell the story of where you come from. I’m a Jazzy Jeff fanatic, and I love Will Smith as a person. When Will Smith came out with “Parents Just Don’t Understand,” that was where he was at the time. Presenting yourself to the world with your truth is always going to win. I want to know your world, and you should want to know my world. That’s how we learn from each other.

This program was co-presented by Arts at MIT and TapTape. Details about upcoming lectures forthcoming. Read more about the Hip Hop Speaker Series.