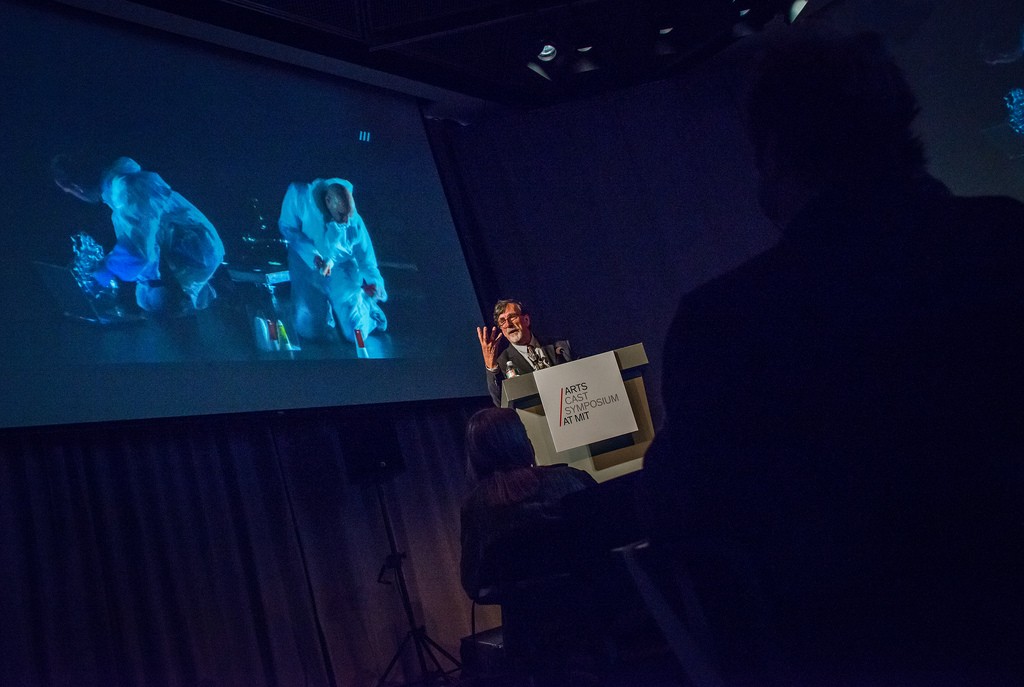

In his keynote address for CAST’s first symposium, Seeing/ Sounding/ Sensing, Bruno Latour (Professor at the Institut d’études politiques de Paris) observed that “Much of our philosophy comes from the still life; it’s a disease of the Dutch. Descartes and Locke spent a lot of time in Holland and saw too many still lifes.” With the joking aside, Latour elaborated on how the still life is emblematic of “matters of fact,” which dull the senses.

The traditional relationship between subject and object that a still life sets up is false. Citing the art historian Erwin Panofsky’s writings on perspective, Latour emphasized the artificiality of the construct in which a subject views objects through an imaginary plane with monocular vision. In reality, objects have a trajectory; they are not fixed. Latour suggested that to be aesthetic – in its true etymological sense, meaning “to make oneself sensitive to” – it is better to imagine oneself in motion in the world.

Latour’s directive to approach things dynamically and from all sides could be seen as the guiding principle of the symposium itself. The symposium’s organizers MIT Professors Caroline Jones and Stefan Helmreich, along with Mellon postdoctoral fellow David Mather, brought together artists, philosophers, cognitive neuroscientists, historians, anthropologists and scholars from various branches of the humanities to contribute to this cross-disciplinary investigation of the senses. The speakers explored their respective subjects, “Seeing/Color,” “Sounding/ Resonance” and “Sensing/ Action,” with kaleidoscopic diversity, each illuminating another aspect of sensory experience. Latour stated “I will make no distinction – because that is the goal of our symposium – between making oneself sensitive through scientific instruments or making oneself sensitive through the arts,” and in that spirit, each of the three panels involved researchers from both the science and arts communities.

Seeing/ Color

Caroline Jones (Professor of Art History; History, Theory and Criticism of Architecture and Art Program, MIT) explained how the panel “Seeing — Color,” would eschew the traditional approach to color in which scientists deal with things like wavelength and artists deal with things like hue; instead Artist Tauba Auerbach talked about color and mathematics, and neuroscientist Bevil Conway talked about about color’s emotional and affective properties. Tauba Auerbach, who works in a broad range of artistic media, including painting and book arts, spoke of how we are bound by our biology to see differently from one another and how her interests in tetrachromacy and the fourth dimension inform her work. Bevil Conway (Associate Professor of Neuroscience, Wellesley and Lecturer on Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School) focused on the computational goals of color and the way the brain achieves these goals. Conway explained the primary role of color is not simply to aid in object segmentation, but rather as a trainable system that facilitates the rapid detection of behaviorally relevant objects. As Latour noted, Conway showed that color is not fixed and is based on a temporal dimension, rather than a spatial one.

Sounding/ Resonance

“Sounding/ Resonance” brought together a musician, a cognitive scientist, musicologists and historians to discuss the manifold topics related to human audition and the “sonic, tactile and haptic” qualities of resonance. In his introduction to the panel, Stefan Helmreich (Elting E. Morison Professor of Anthropology and Head, Anthropology Department, MIT), mentioned the image of the human as the Aeolian harp – as a sensitive, an attuned being. This metaphor was the Romantic counterpart to Latour’s definition of aesthetic. Beyond addressing the technological, historical and scientific approaches to understanding sound, the speakers commented on the larger issue of sensitivity. For instance, in his interview with Brian Kane (Assistant Professor of Music Theory, Yale University), composer Alvin Lucier (John Spencer Camp Professor of Music, Emeritus, at Wesleyan University) shared his prescription for creative exploration: “It’s wonderful to have a blank mind. You’ll let anything enter.” He had offered this response to the naysayers who thought using brain wave amplifiers in Music for a Solo Performer was a gimmick. When asked about Latour’s definition of aesthetics, Lucier responded that his work sometimes prompted listeners to be attentive to the process of hearing itself rather than to focus on the music as something external to them. Josh McDermott’s (Assistant Professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, MIT) talk on auditory perception seemed like something of a primer for listening to Lucier. He explained the way sound waves interact with room acoustics on the way to the ear, the very phenomenon that Lucier exploits in I Am Sitting in a Room and In Memoriam Jon Higgins, the pieces featured in the evening concert.

Sensing/ Action

The panelists in “Sensing/ Action” addressed concerns closely linked to the topics put forth in Latour’s keynote. Carrie Lambert-Beatty brought up the idea that neural activity depends on interaction with the world. Artist Tomás Saraceno’s discussion of his work On Space Time Foam in the Hangar Bicocca Milan (2012) in relation to his fascination with the “butterfly effect” and the notion of proxemics (from the book The Hidden Dimension) echoed Latour’s thoughts on the implausibility of a fixed face-to-face interaction with our environment. Latour pointed out in his critique of the “still life” scenario that not only are subject and object in flux, but also the background itself, planet Earth, is changing in our current climate crisis and requires new responses. Saraceno’s ever-shifting mutable installations create exactly this kind of fluctuating environment, which challenges us to find unusual ways to sense our world.

Neuroscience and Humanities/ Intersections

With the burgeoning influence of neuroscience into an ever-expanding number of disciplines, there is diverse group of academics who want to drink from this particular cross-disciplinary fount. Natasha Schüll mentioned her work in neuroeconomics in the “Sensing” panel, but recent years have also seen a number of forays in the neuro-humanities. The attendance at CAST’s Symposium was evidence of growing enthusiasm for this kind of scholarly exchange; there were nearly 800 registrants from destinations across Europe and North America representing a wide array of humanities and visual arts disciplines with many more participants viewing the proceedings online.

The two-day event highlighted some of the intriguing intersections among the arts and sciences, not the least of which is the drive to put theory into practice. Artists and scientists alike probe the realities of sense experience, albeit with different tools, as Latour pointed out. The symposium’s concluding concert, which featured performances by Alvin Lucier, Evan Ziporyn and Arnold Dreyblatt, reinforced the theoretical discussions with experiential knowledge of sound itself and of our own abilities to sense and to be aesthetic.

View the CAST symposium in its entirety or read full transcripts of all the sessions.