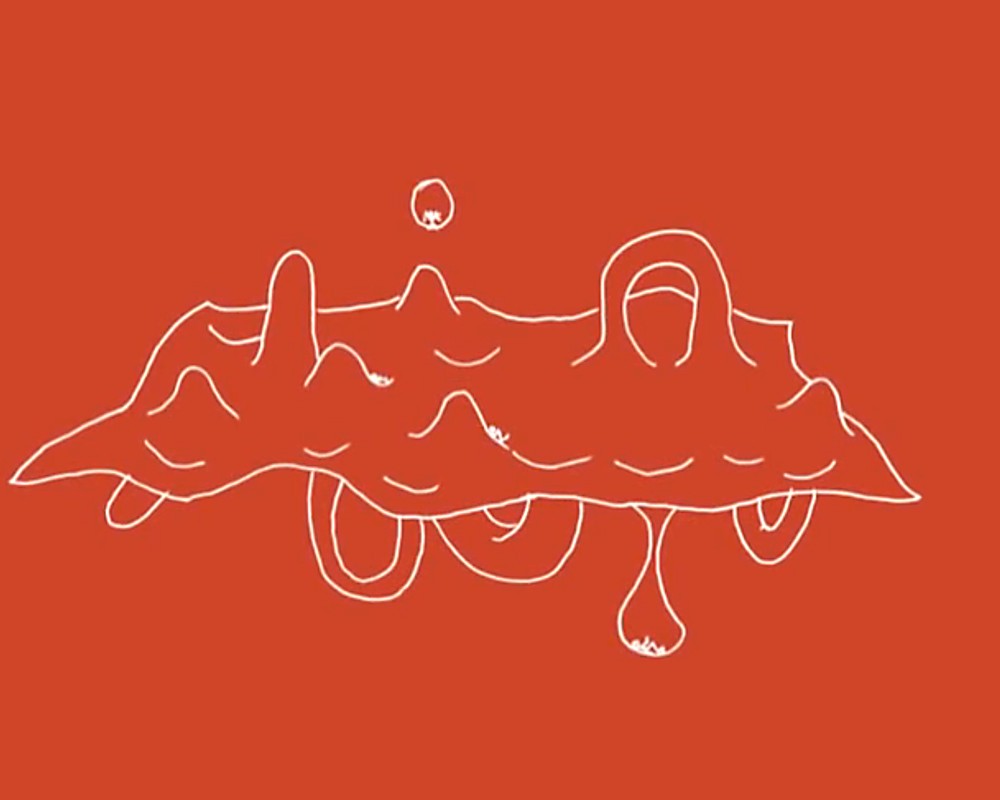

“It’s 99.9 percent air,” says artist Tomás Saraceno of his latest work, “On Space Time Foam.” On Space Time Foam is a multi-layered habitat of diaphanous membranes suspended 24 meters above the ground, its form continuously shaping and shaped by the actions of those who dare be enfolded within the billows and wrinkles of its inflated topography.

What steel was to the cities of the 20th century, perhaps air will be to those of the new millennium. Water, air and gas — the most mercurial of substances — are the materials of the artist, whose visit is sponsored by the Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST) and the Department of Architecture. With these materials, he constructs feedback loops activated by the presence of visitors within them. Like a biosphere, where water cycles around through the processes of evaporation and condensation, “On Space Time Foam” is an ecosystem. It makes tangible the complex systems of interaction, both physical and social, between humans and their environment.

Trained as an architect and inspired by the utopian ambitions of such visionaries as Buckminster Fuller, Saraceno creates installations that express an aerial vision of a more interconnected existence. “It’s like Airship Earth,” Saraceno says, alluding to Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. The dream of his ongoing series, “Cloud City,” is not only to live among the clouds but also to create cities more like clouds — changeable, mobile and responsive to atmospheric shifts, on both the natural and cultural scale. Saraceno’s works “refuse to be subordinated to tectonics,” remarked Nader Tehrani, professor and head of the Department of Architecture, who moderated Saraceno’s public lecture on Nov. 15, “Moving Beyond Materiality,” along with fellow Professor of Architecture Antón García-Abril.

The forms of Saraceno’s pneumatic structures often mimic the latticework of molecules, the crystalline designs of spider webs, soap bubbles and neural circuits. In these forms, constituting the most basic patterns of existence, Saraceno searches for a universal language, the cosmic shape that unites life on earth. He searches for the forms — from the tiniest spider web to the structure of the universe — that configure life on earth.

Most of his works are variations on a theme: transparent envelopes of air suspended high above the ground. These envelopes may contain plant life, water, air or bodies; they are blueprints for incubating a world in the sky. Feats of engineering, the installations possess a delicate yet nimble strength — and they are getting more elaborate. With the help of scientists and engineers — including those at MIT — Saraceno is moving closer toward realizing this vision.

If earlier iterations were more symbolic statements — poetic suggestions for all that could be — his more recent projects edge nearer to this airy utopia. In 2010, Saraceno collaborated with arachnologists to model in 3-D the intricacies of a Black Widow spider web, a form thought to mirror the structure of the universe. This kind of complex digital visualization had never before been achieved, and led to a plethora of new insights, both scientific and artistic. A collaboration between different disciplines and institutions, the work resulted in a hand-knotted model 30 times the web’s original size. While attending NASA’s International Space University, Saraceno subsequently proposed to send the spiders up to the near weightlessness of NASA’s space labs in order to study, with a team of scientists, the effects of microgravity on their webs.

At MIT, Saraceno had the opportunity to draw upon a vast array of expertise in departments across the Institute: aeronautics and astronautics; biology; physics; chemistry; electrical engineering and computer science; mechanical engineering; civil and environmental engineering; earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences; architecture; science, technology, and society; and media arts and sciences. Swinging between the practical and the speculative, Saraceno discussed everything from nanoengineered materials to solar energy to weather patterns to the origins of the universe. He asked scholars in diverse disciplines to imagine with him what a different reality might look like.

To defy gravity, after all, is part of Saraceno’s ultimate goal in conceptualizing a more sustainable future. In his vision, inflatable pods would take off in flight, rising skyward to colonize the cloudscape. Propelled by currents of wind, these self-sustaining modules would always be drifting and reshaping into endlessly malleable new formations, loosened from the constraints of geopolitical borders. “It’s a public space made up of very small spheres,” he says, imagining a community defined by greater freedom and mobility, both physical and intellectual.

What the cloud city offers is a new paradigm for thinking about humanity’s relationship to the natural world and to one another. While conventional logic invests human beings with all the power to change the environment, Saraceno’s installations model the dynamic interplay between human and non-human agents in a complex network of organisms, materials, and natural forces. They reflect an increasingly interconnected world — environmentally, politically and socially — in which the smallest of fluctuations (say, a dip in the market) has far-reaching global consequences.

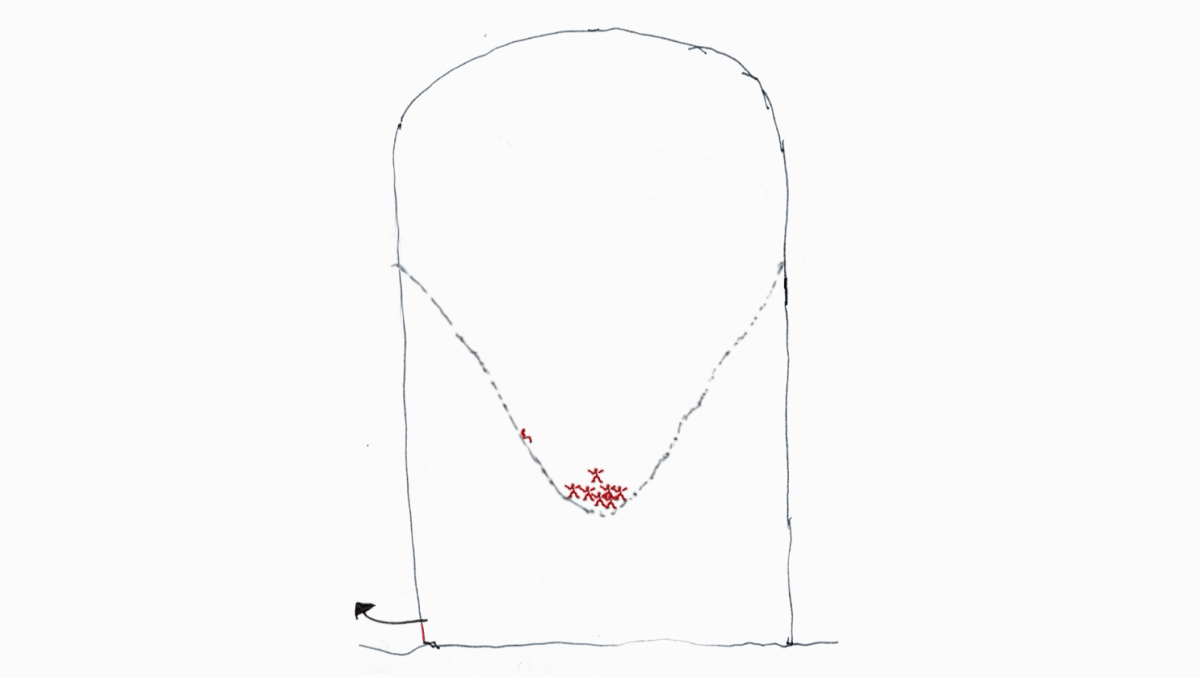

This butterfly effect is physically manifested in “On Space Time Foam,” which is currently on display at Milan’s HangarBicocca and will later form the basis of a floating biosphere in the Maldives Islands made habitable with solar panels and desalinated water. As visitors slide through these pressurized sacs of air, each layer with its own climate, their movement produces a reaction throughout the entire installation. When visitors cluster too close to one another, the force of their combined weight can lead to what Saraceno calls a “black hole of social interaction,” referencing the cosmological theories of that informed the piece. In his work, everything is connected.

“I am trying to make people engage and tune with each other,” Saraceno notes. To be sure, the artist is more of a composer than an urban planner. He calibrates densities — whether that of a bead of moisture in the air or the weight of a passing footstep — and, in doing so, reminds audiences of the world’s overwhelming sensitivity and intricacy.