By Evan Ziporyn, Kenan Sahin Distinguished Professor of Music at MIT and Faculty Director of the Center for Art, Science & Technology.

I first heard Arnold Dreyblatt’s music while couch surfing in the early 1980s, in a loft in what we still were getting used to calling Tribeca. The picture on the album cover was enough to do it for me, but the music was something else entirely. Metallic shards of overtones, emanating from what I eventually learned to be Arnold’s bass, in simple but mesmerizing rhythms, shooting off in all directions, latched onto by other instruments with similarly resonant qualities – his Orchestra of Excited Strings. Everything was transparent, and yet the range of colors was broad and everchanging, the grooves as earthy as a Bo Diddley tune. Nothing was hidden, it was all acoustic music, no processing or effects. There were no tricks and no sleeves, and yet the music was magical.

For last Wednesday’s talk, Arnold began with first principles: a chart from John G. Roederer’s 1973 Physics and Psychophysics of Music. It strips music down to its material essence, how sounds are made and how they are received.

On some level we all know that this is the basic mechanism, mainly we try to ignore it so we can get on with the business of communicating: speaking or singing, perceiving and interpreting. In everyday life – including most music-making – it’s best taken for granted, not meant to be noticed. But Arnold has built his music – quite literally – by keeping it in mind. Taking the minimalist model to an extreme, he eschewed all received cultural and historical ideas – major scales, raga, maqam; violins, sitars, shakuhachi – and constructed his music from the building blocks of sound and perception, the overtone series and the ‘tendency of many objects to vibrate more vigorously’ at certain frequencies, i.e., to resonate. He invented as needed instruments, playing techniques, scales, and harmonic systems.

One of his first instruments – and still the fundament (literally) of his music – was a modified double bass, restrung with piano wire and bowed in a percussive manner to produce an everchanging array of dancing, metallic overtones. These ‘partials’ are the same wherever they’re found, anytime (as Arnold put it) ‘strings are scraped or pipes are blown through’ – or for that matter any time our refrigerators and electric toothbrushes sing to us.

The discovery of intervallic ratios is sewn into various cultural narratives – Pythagoras in Greece, the Yellow Emperor in China – and in many ways what distinguishes musical systems are their methods of organizing and prioritizing them: the cultural definitions of consonance, dissonance, emotional affect, etc. Partials are the phonemes of music – in fact, vowel distinction is primarily determined by the overtone structure of the voice. Further, these same numeric ratios, which at high frequencies produce intervals, when slowed down are heard as meter and rhythm – hence the earthy grooves. Paradoxically, by basing his music on these ratios, Arnold creates a music that connects to myriad cultures – didjeridoos in Australia, Tuvan throat singers, Sardinian tenores, Vietnamese zithers, Indian raga, etc.

We began working together in the late 1990s – I helped him translate his ratios and frequency charts into a symbol system more palatable to the ‘trained’ musician – i.e., ‘standard notation.’ In return I got my initiation into the world of Just Intonation, a gift that keeps on giving. (I also brought him to MIT in 2000, and we started a band with some of my NY buddies and two MIT undergraduates, Jeff Lieberman and Laurel Smith Pardue. We played a few dates until Laurel was called back to the Air Force.)

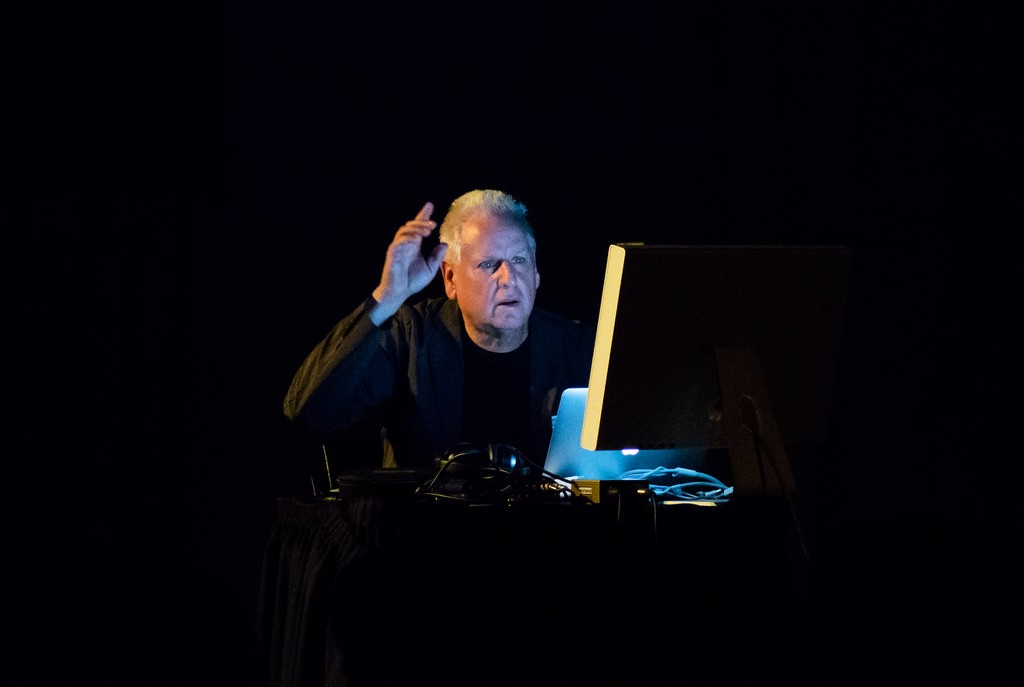

The cover photo mentioned above comes from the Horus Archive, a strange and beautiful collection of found photographs mainly from Hungary and environs (well worth a visit, but that’s another story). To me it’s a window into an equally important part of Arnold’s work, a substantive body of installation art based on archive and memory, particularly the lost memories of central & eastern European Jewry. In his installations, at the HL Holocaust Center in Oslo and the Jewish Museum Berlin, among other places – the printed word take on the multifaceted function of the overtones of his doublebass, in varying states of motion and transparency, floating through the space through various means of projection, resonating now metaphorically, with the associations in our minds. Names and occupations, lists of possessions that were later seized, the bureaucratic minutiae of unsuspecting everyday life. As with his music, the greater historical and cultural context – in this case, the Holocaust itself – is unmentioned: the power of the work stems not from its evocation, or even by any display of any overt emotion, but rather simply by the illumination and refraction of all that was lost./>

Given his preoccupation with resonance, acoustic and metaphorical, it was perhaps inevitable that Arnold has become interested in MRI technology, not just for what it reveals about the body and the brain but for what it is on an experiential level. As those who undergo it or manage it know, Magnetic Resonance Imaging has a sound – albeit one found by many people to be at best an annoyance, contributing to the going back to first principles – it follows the same acoustic principles as does a vibrating string or blown pipe – the hidden chords of the overtone series. His most recent CD is a composition for MRI machine – the ‘score’ consists of specifying various scans – ‘knee’ ‘ankle’ – so for many researchers it may seem like a busman’s holiday. For Arnold though, it’s the sound of a search for memory – a sound he’s been evoking in his work for over 30 years.