Albert Figurt’s residency at MIT CAST has involved Grammy-winning rappers, guerrilla filmmaking, and generating some vapor-rich STEAM from STEM students

Cambridge, MA—“Is it possible to make a film without cameras, or to develop a story without sounds?”

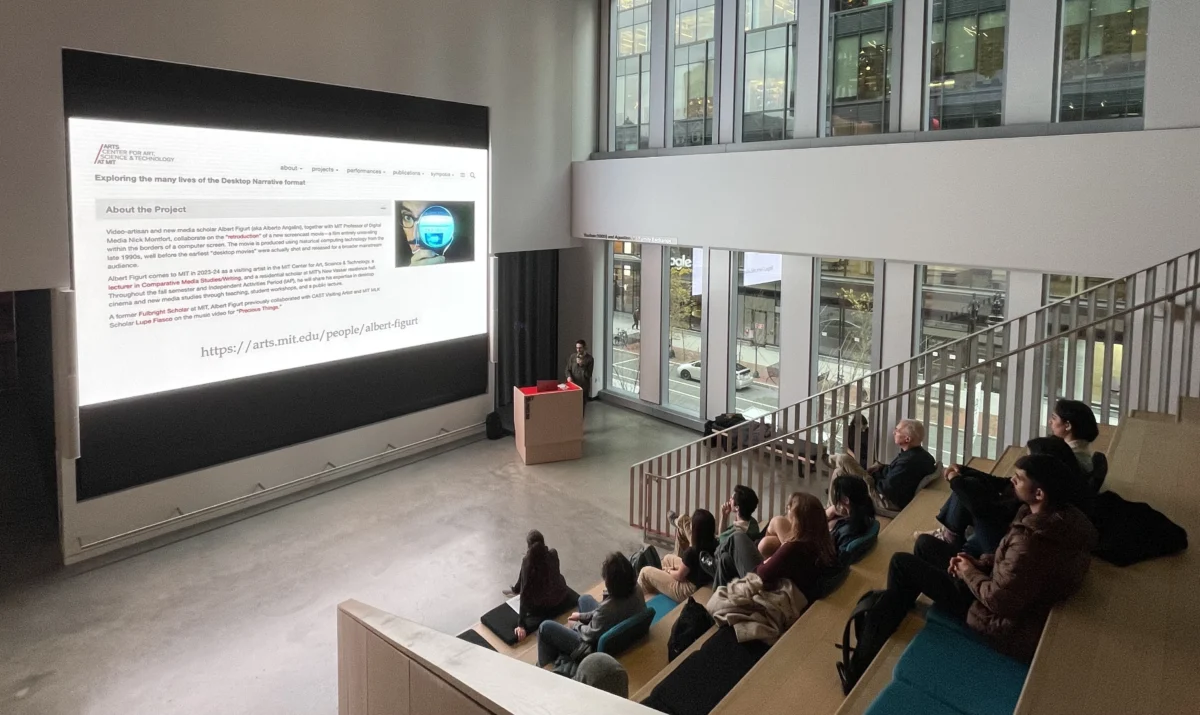

Albert Figurt has a mischievous smile on his face as he engages with more than a dozen MIT community members at the new InnovationHQ space in building E38. He lectures the way he talks, and talks the only way he knows how: a mile a minute, in a vibrant Italian accent, with excitement and enthusiasm and no shortage of recombined and parenthesized phrases and figur(t)es of speech, like “bureaucraZy” and “collaboraCtion” and “creativiTheory.”

The questions that he is asking at this two-day “guerrilla filmmaking” workshop get at the core of the lo-fi approach that brought him to MIT nearly two years ago, first as a Fulbright Scholar and now as a visiting artist in The Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST). Over the past decade a wide range of tech advances have democratized movie-making such that anyone with a phone and an internet connection can share their creations with the world. Figurt has been there along the way for the field’s many evolutions, producing cutting-edge video art and investigating how artists have increasingly looked beyond physical film to explore different ways to tell stories.

This past semester Figurt has shared his cinematic expertise with MIT students and colleagues through myriad forms, from organizing screenings and YouTube jam sessions in the New Vassar dorm (where he was living as a Residential Scholar) to teaching the undergraduate class “Making Documentary: Audio, Video and More” in Comparative Media Studies/Writing (CMS/W)—not to mention several artist talks around campus and two experimental workshops during January’s Independent Activities Period (IAP). He also collaborated with MIT professor Nick Montfort in refining a new digital media technique called “retroduction” (from retro+production), which seeks to reverse the idea of “technostalgia” by exploring and expanding “past technologies that did not find their cultural expression.”

Figurt’s latest obsession has been desktop cinema, an emerging paradigm that puts the camera’s focus entirely on our computer screens. He views it as a uniquely self-referential format that uses our enmeshed relationships with technology to explore themes such as privacy, loneliness, addiction, and even cyberbullying. He has an ever-growing research blog on everything “desktopian,” which includes a dedicated “desk-talk” series about how media scholars and digital artists use their desktops. He also developed a “Desktopia” theater workshop for IAP that pushed participants to frenetically assemble and present a 40-minute performance piece exploring our relationships with screen-based devices in the space of just eight hours.

Figurt isn’t the only one intrigued by the potential of desktop narrative: “screenlife” movies like “Unfriended” and “Searching” have made more than $100 million globally and demonstrated the public’s growing interest in new cinematic forms that more directly reflect how we interact with technology. Meanwhile, on the academic side, desktop-based video essays are slowly becoming the new norm when it comes to engaging audiovisual criticism.

Montfort has been a close collaborator with Figurt on desktop cinema projects and applauds his “insatiable” thirst to learn about new disciplines and explore adjacent avenues of creative inquiry.

“Bringing him here seemed like a great combination of his connection to the cinematic, and my interest in the deeper computational elements that inform our experiences with technology,” says Montfort. “Both of us share an interest in peering out at the horizons well beyond our particular domains.”

Maria Alder ’25 was in Figurt’s documentary class, where she made a film about Boston bike lanes and came to appreciate him as a teacher, mentor, and artistic inspiration.

“I admire the unique topics and approaches that he explores in his work, as it’s always very intentional and creative,” Alder says. “Each class felt more like a conversation, and one in which Albert would actively engage with students and provide unique insights and perspectives.”

Spending time inside the belly of a beast as eccentric as MIT has been a fun fish-out-of-water adventure for Figurt, who participated in Lit Tea parties, hung out in the Banana Lounge, and even sat on a team of world-champion puzzle-solvers at the annual Mystery Hunt. He credits MIT for being a space of “constant collateral overstimulation,” where technologists, creators, and academics “converge to explore new modalities and methods for self-expression.” He found it enlightening to work with engineers, coders, and other community members who don’t view themselves as artists, and who are trained to approach every task with chess-like concentration.

“My teaching goal was to help students pass through this tunnel of the humanities using the arts to transform STEM into STEAM,” he says. “The result is a lot of vapor, which can be cloudy and confusing, but refreshing in how it opens the pores.”

Figurt also actively collaborated with another CAST Visiting Artist: Grammy-winning rapper Lupe Fiasco. The duo serendipitously met last year and quickly found themselves having free-wheeling discussions about everything from hip-hop sampling to the next generation of conspiracy theorists jumping down internet rabbit holes. Fiasco was so taken with Figurt’s work that he enlisted him to write and direct a cryptic desktop music video for “Precious Things,” a single from his 2022 album Drill Music in Zion.

“In my book Albert is one of the world’s top 5 intellectuals, no exaggeration,” says Fiasco. “He is an activist and agent provocateur whose work is embedded with an edge and layers of subterfuge that make you think about things in deeper ways.”

As the clock ticks on his time at MIT, Figurt is wrapping up several projects that he hopes to finish by the end of the year—but what sticks with him most is the complex “motley stew” of scholars and creators that has stimulated his work both intellectually and artistically.

“Some people can explain but can’t produce, while some can produce but not explain,” says Fiasco. “Albert is one of these minds who can blend theory and practice, and neither suffers.”

Figurt is a Visiting Artist through the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST) with the financial support of the Alan W. Katzenstein (1942) Memorial Fund and MIT CMS/W.

Editorial direction by Leah Talatinian, Arts at MIT

Written by Adam Conner-Simons