Part magic, part social experiment, visiting artist Jeanette Andrews’ “The Attestation” examines preconceived notions and belief polarization

At a time when people across the country and the globe have never seemed more polarized, it may sometimes take a different kind of perspective to bridge political divides. For Jeanette Andrews, that might require a little bit of magic—quite literally.

The first illusionist to be picked to join the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology’s (CAST) Visiting Artist program, Andrews spent the past two years working on a complex multi-disciplinary project spurred by her collaboration with MIT professors Graham Jones and Arvind Satyanarayan. Jones is an anthropologist who studies magic, while Satyanarayan is a computer scientist specializing in data visualization. Their research on misinformation inspired Andrews to reflect on the fundamental core of what magicians aim to do: “create visual misinterpretations.”

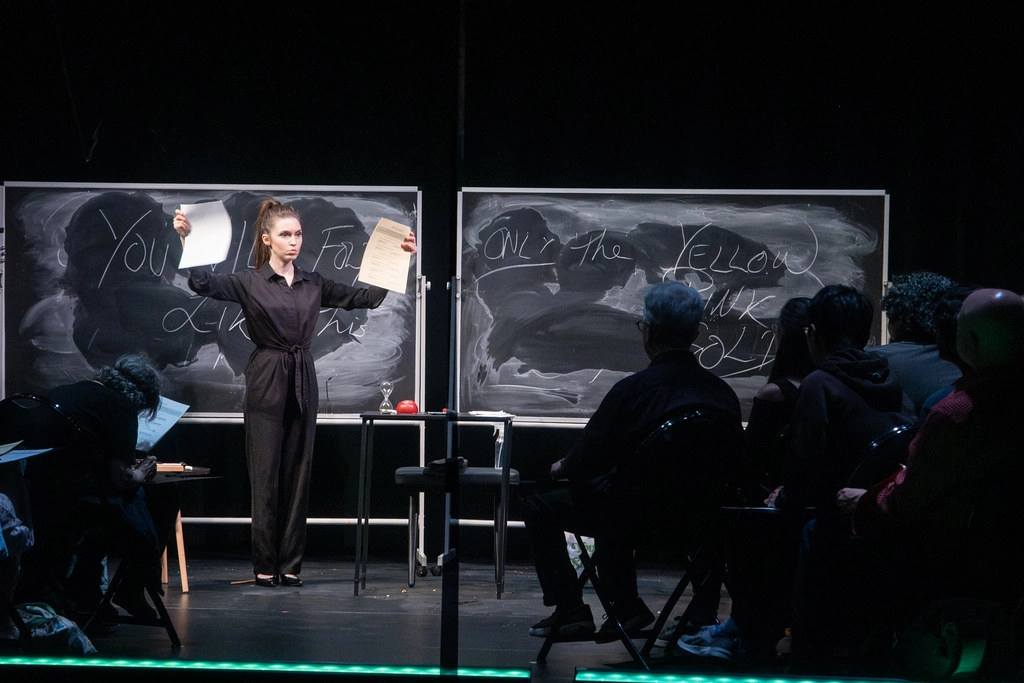

Andrews’ piece, “The Attestation,” is a site-specific performance exploring belief polarization that she presented October 3 and 4, 2025 at MIT’s Kresge Little Theater. Drawing its title from the word for “a proof or official verification of something through evidence,” the work is part magic show and part social experiment, lavishing in the messiness that can emerge when people find themselves thrust into opposing viewpoints.

“The Attestation” explores a concept in the world of magic known as “the convincer” —an action or action that tells viewers that conditions are normal, or that makes the magic effect seem more impossible.

“The idea is that, while watching the exact same magic tricks, viewers would have opposite interpretations of the things that are supposed to build their trust,” says Andrews.

Audience members were thrust into mystery before the show even began, getting swiftly divided into several groups at the box office and whisked into different pre-performance “VIP receptions” across the lower level of Kresge. It only became clear at the very end of “The Attestation” that the groups had dramatically different pre-show experiences that shaped their perception of the illusions being performed.

Specifically, the two groups’ VIP rooms taught them subtle structures of cause and effect that they would mentally carry with them into the performance, inspiring skepticism of different actions—in one case, fabric being pushed or pulled up, and in another, objects pushed toward the center of a space. Andrews then presented a piece of magic that incorporated these “convincer” gestures to create second-by-second divergent beliefs amongst the groups.

In a series of wordless surveys that Andrews conducted mid-performance by having audience members shine flashlights at a series of charts, it became clear that the two groups had been primed to have diverging reactions to different actions of Andrews—the “object-push” group became more skeptical when they saw her move items away from the center of a table, while the “fabric” group became more skeptical when they saw her engage in the classic magician act of pushing up her sleeves (“nothing to see here!”).

Or did they? Post-show discussions brought audience members from these different groups together to parse the particulars of the experience. Through a mediated discussion, each group was invited to question not only what they believed, but why. Some even wondered aloud if Andrews herself had gently manipulated people’s responses in real-time as some sort of meta-commentary on how easy it can be for bad actors to “massage” scientific data. (A third group of attendees were a “hidden audience” behind a one-way mirror in the back, which Andrews included to explore the idea of “speculative belief” involving individuals who were not primed in any particular way.)

“With magic you know in advance that you’re going to see something that you can’t explain, but you don’t even know what the something is, so you’re basically hyper-scanning for any sort of anomaly to explain things,” Andrews says. “It’s similar to what we see in a lot of confirmation bias that happens—people hyper-scanning for anything that confirms the belief that they’re holding onto.”

Jones said that “The Attestation” raised questions about the nature of belief not only because audience members got the chance to compare their different experiences within the performance, but also because Andrews called attention to something fundamental to the nature of magic itself..

“As a viewer, it can be hard to fully believe the unbelievable, but if you’re too suspicious, you’ll be fixated on trying to find an explanation rather than actually enjoying the experience,” Jones says. “Magic is a unique form of performance in that it involves suspending belief just enough, but also suspending skepticism just enough.”

Indeed, Satyanarayan says that that suspension of skepticism, in particular, was apparent during the post-show debrief as the audience came together in a collective act of trying to make sense of the experience.

“Magic sets a frame for audiences, such that we enter this liminal space where people have suspended their beliefs to different degrees, and no one actually knows the absolute truth,” Satyanarayan says. “There was a sense [during the debrief] that you’re not trying to prove that you’re smarter than anyone else, because you’re just as in the dark about what’s going on as anyone else.”

As part of Andrews’ year-long residency she gave multiple presentations to the MIT community examining similar subjects. At an opening event for the Schwarzman College of Computing, she led an interactive game based on “telephone” that explored how the retelling of sensationalized information morphs across groups based on data labeling. She joined Jones’ “Magic, Science and Religion” course to help students construct and perform their own belief-altering parlor illusions. And she participated in Jones and Satyanarayan’s new “Human User Experience Design” class to discuss how designing for surprise could lead to more humane AI systems..

“The collaboration with Arvind, Graham and everyone at MIT was something that deeply drove the direction of the work and the themes that we explored,” Andrews said. “This experience profoundly changed me as a performer, artist and human being, and I’ll be eternally grateful for that.”

Jones also considers Andrews’s residency a resounding success. Magic, he says, is an ideal medium for sparking conversations about how our minds work, an exciting topic for a place as cerebral as MIT..

“When a magician fools you, it can lead to a kind of humility about our own limitations as rational beings,” says Jones. “It invites us to reflect on our own cognitive and perceptual habits, and to maybe think a little bit more critically about why we believe what we believe.”

Written by Adam Conner-Simons

Editorial direction by Leah Talatinian