Nell Breyer’s installation “Where Lines Converge,” on view in Manhattan’s Central Synagogue, asks what it means for bodies to convene and perceive themselves as a collective.

The artist Nell Breyer ‘02 has long been fascinated by the relationship between bodies and space, as a masters student in the MIT Media Lab (2000-2002) and as a research affiliate at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (2002-2010). So when Central Synagogue in Manhattan asked her to create an installation that would reinvigorate its soaring sanctuary and welcome people back to in-person services, the project was an ideal match.

As a member of the congregation herself, Breyer was familiar with the function and meaning of the space, and wanted to create a piece that would complement its grandness and serenity. “It’s a very rich, ornate, and beautiful sanctuary,” Breyer says. “I was very aware of the challenge of trying to insert something that doesn’t prevent people from being together, especially in a spiritual context and in a religious practice.”

The resulting piece, “Where Lines Converge,” is now on public view through June, during Central Synagogue’s visiting hours on Wednesdays from 12:30-2:00 p.m, Fridays during Shabbat services 6:00-7:00 p.m. and by appointment. Breyer used simple raw materials to create the installation’s stunning and dynamic visual effect.

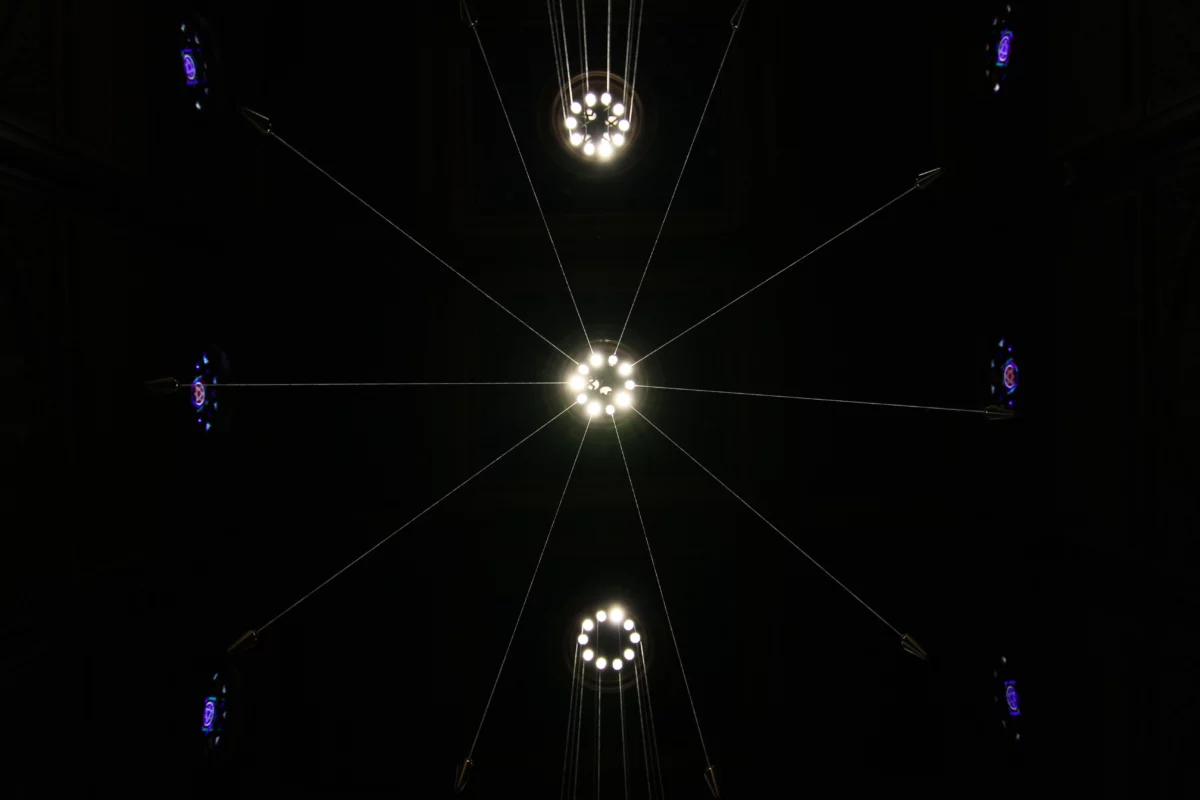

Brass weights, known as plumb bobs, are attached to strings suspended from the ocular lights that run the length of the central aisle’s 60-foot ceiling. The strings are evenly spaced from one another in a series of six circular shapes, following the symmetry of the architecture. But because the length of each string was roughly measured by hand, there’s an element of irregularity to their heights, which leave around 9 feet of clearance below them for people to walk the aisle. If you stand beneath one of the circles and look up, the strings seem to converge to a single point, an optical illusion that’s key to Breyer’s design.

“I wanted to create a work that would operate like an action, not an object,” Breyer says. Plumb bobs have been used for thousands of years as a tool for measurement, including during the construction of the Egyptian pyramids, Breyer notes. In “Where Lines Converge,” the brass weights are actively measuring the height of the sanctuary, even as they combine into a work of art.

“The origins of this piece came from a series of works I did about vanishing points and the relationship of the individual’s body to changes in the landscape, light, and air around us that we feel but we can’t see,” Breyer explains. If you look closely, the strings are often in motion, responding to the breeze from an open door or to music being played in the room. Even while emphasizing the stillness of the sanctuary, “Where Lines Converge” measures how it’s constantly alive to activity and the people who convene there.

“I’ve always been interested in how we perceive the invisible parts of movement,” Breyer says. “How do you make apparent what it’s like to congregate in this space and feel the vibrations and the music and the air? And the ebb and flow between my individual body and everyone around me?” These curiosities stem back through Breyer’s time at MIT, where she worked on public installations and projects with artists who shaped her way of thinking, including former director of CAVS Krzysztof Wodiczko, who served as her thesis advisor, and Steve Benton, the inventor of the rainbow hologram, who invited her to become a research affiliate.

“Over that decade that I was at MIT, I had the chance to experience an extraordinary range of work, some of it very technical and some of it delightfully analog,” Breyer says. “The projects I worked on at MIT have influenced my trajectory, almost all of them about human movement in public spaces, and how our own bodies orient to understand, perceive, and reconfigure those kinds of flows.”

Breyer’s last project on campus, created as part of MIT’s 150th anniversary celebration, combined choreography and video installation on the site of Sol LeWitt’s permanent public art piece “Bars of Colors Within Squares,” which surrounds the Green Center for Physics. “It’s one of the treasures that reside in the campus that continues to make me think a lot about how we experience bodies and space,” Breyer says.

A Boston native who studied painting at Yale, Breyer says a class there about the cellular basis of behavior sparked her interest in “how the architecture of our brain, and specifically of our visual cortex and our sensory motor function, influences how we perceive the world.” She went on to study neuroscience at Oxford University, and later the MIT Media Lab offered Breyer a rich combination of resources and rigor that has shaped her ongoing artistic practice.

“The Media Lab was a really amazing melting pot for me, because I could use some of the science and some of the media, arts, and technology and be in an amazingly experimental community that’s open to a lot of bleeding edges,” Breyer says. “MIT offers a very unusual combination of this incredible freedom to experiment and explore, combined with an unparalleled technical virtuosity and specificity, especially in science and engineering.” The breadth of resources, including collaborating with other artists, faculty, and students, pushed Breyer to investigate her artistic interests with scientific precision.

“It’s such a privilege to be part of a community where you have that freedom, and where the expectations and the standards are enormously high, so you hold yourself accountable,” Breyer says. She was especially grateful for the opportunity to embrace a variety of mediums and an expansive understanding of how art can interact with life, a relationship Breyer has continued to explore with pieces like “Where Lines Converge.” “MIT really supports interdisciplinarity, which I love as an artist,” Breyer says. “Because real life doesn’t respect rules of separation.”

Written by By Naveen Kumar

Editorial direction by Leah Talatinian