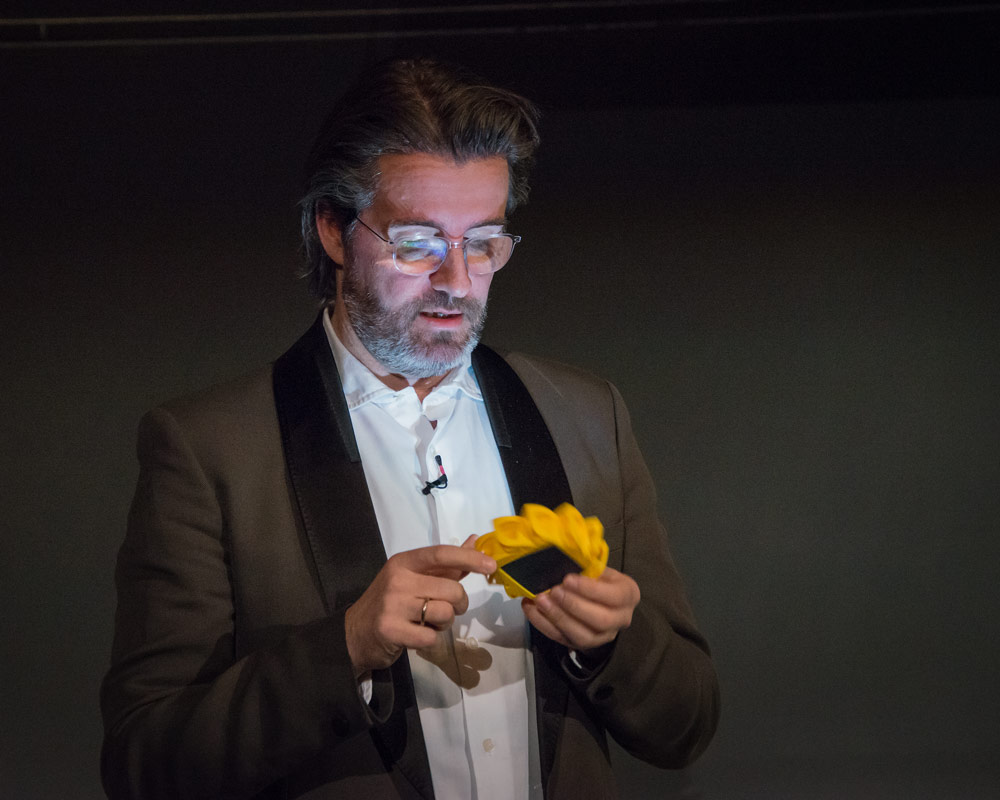

“The ephemeral light from Berlin traveled with me on the plane and came to Boston,” announced the artist Olafur Eliasson in his recent sold-out lecture at MIT, a sunflower-shaped solar lamp in hand. As the recipient of the 40th Eugene McDermott Award in the Arts, the Danish-Icelandic artist was on campus recently to accept the award and meet with faculty and students across the Institute about his latest art project and venture in social entrepreneurship, Little Sun, a solar-powered lamp that aims to deliver sustainable energy to the 1.6 billion people without access to electricity.

With the cross-school MIT Energy Initiative (MITei), vast range of faculty expertise, and rich culture of innovation, Little Sun could not have landed in a more receptive place.

And yet, for Eliasson, Little Sun is more than just another utilitarian device designed to solve the world’s problems; it is also a way for people to feel more empowered and connected to one another. The lamp is a materialization of one of the most abstract concepts — energy — which can be passed around and shared among people across the globe. The lamp, capturing and storing precious rays of sunlight, provides what Eliasson calls “the right to power” — a way of “holding hands with the sun,” he likes to say.

In summer 2012, Eliasson launched Little Sun alongside engineer Frederik Ottesen, who had previously experimented with building a solar-powered airplane (“I tend to have a passion for the slightly impossible,” Ottesen admits). For Ottesen, working with an artist like Eliasson brought an indispensable perspective. “[Before Little Sun] I had not learned how to put any kind of emotion into a piece of plastic,” Ottesen says, adding, “There was no product on the marketplace that inspired happiness.” Together, the pair created a product designed not only to provide light, but also evoke desire, inspiration, and self-confidence.

With its bright butter-yellow color, Little Sun is designed to appeal to mothers and children, as a solar alternative to the kerosene lanterns used in many countries. For the price of two to three months’ worth of kerosene, this rechargeable solar lamp can provide a family with ten times brighter light for years, without the serious health and environmental impacts of burning kerosene. Slowly, Eliasson says, Little Sun is transforming the way we use and distribute energy, one lamp at a time. “If I’m a child who reads my bedtime stories from this light, maybe I will be more likely to build a sustainable house,” Eliasson says.

Little Sun first came to MIT last fall, when CEO Felix Tristan Hallwachs, the former manager of Eliasson’s robust 90-person studio, came to present the project and mentor students in the annual Hacking Arts competition in September. The hack-a-thon resulted in the formation of three groups who “hacked” Little Sun to create novel new products, which they then showcased at the MIT Museum’s popular Energy Night in October.

Once Eliasson himself arrived on campus, he had the opportunity to further discuss issues of sustainable development, community engagement, design, product engineering, and social entrepreneurship in developing economies. He met with the MIT D-Lab, TATA Fellows, the MIT Sloan School of Management, the Center for Civic Media, Open Documentary Lab, the MIT Museum, and students in the Art, Culture, and Technology program, and the History, Theory, and Criticism of Architecture and Art program. Activities ranged from one-on-one meetings, lectures, brainstorm sessions, and creative workshops.

Eliasson’s interest in “turning thinking into doing” is a perfect fit with MIT’s motto of mens et manus, or mind and hand. Eliasson’s multidisciplinary residency engaged groups across the Institute to creatively expand the conversation around sustainable energy, as well as collectively imagine new and inventive solutions for the future. “It’s an unbelievable moment when you can give an idea shape,” he says.

In many ways, Little Sun is a natural extension of the philosophical ideas that have occupied Eliasson throughout the course of this 12-year career. Many of his works explore the perception of light as it relates to time, space, and movement. As the scholar Marcella Beccaria wrote, “Light is the instrument through which Eliasson relates to each person as a sensuous subject who lives in the realm of daily life.” Through such works, he explores the points at which inner experience intersects with the external world.

Eliasson’s experiments with natural phenomena were on display in his enormously popular installation, The weather project, which debuted at London’s Tate Modern in 2003. For this work, Eliasson installed an immense artificial sun in the Tate’s cavernous Turbine Hall, creating a sui generis immersive environment of ethereal light and fog. The weather, Eliasson suggests, is a way of experiencing both singularity and plurality at once — one of his key conceptual preoccupations. In a similar way, Little Sun straddles the boundary between the individual and the collective, offering users an individual sense of personal power — both literally and figuratively — while also connecting them to others in a global energy system.

Eliasson is interested in collapsing distances — between self and other, between near and far — to emphasize the importance of interdependence. Little Sun, Eliasson says, is “about looking at the planet as one kind of ecosystem.”

2. Frederik Ottesen at Energy Night. Photo: L. Barry Hetherington.

3. Olafur Eliasson Creating Light Graffiti with Little Sun. Photo: Studio Olafur Eliasson.