The digital artworks of Tamiko Thiel ’83 expand perception of our immediate environment

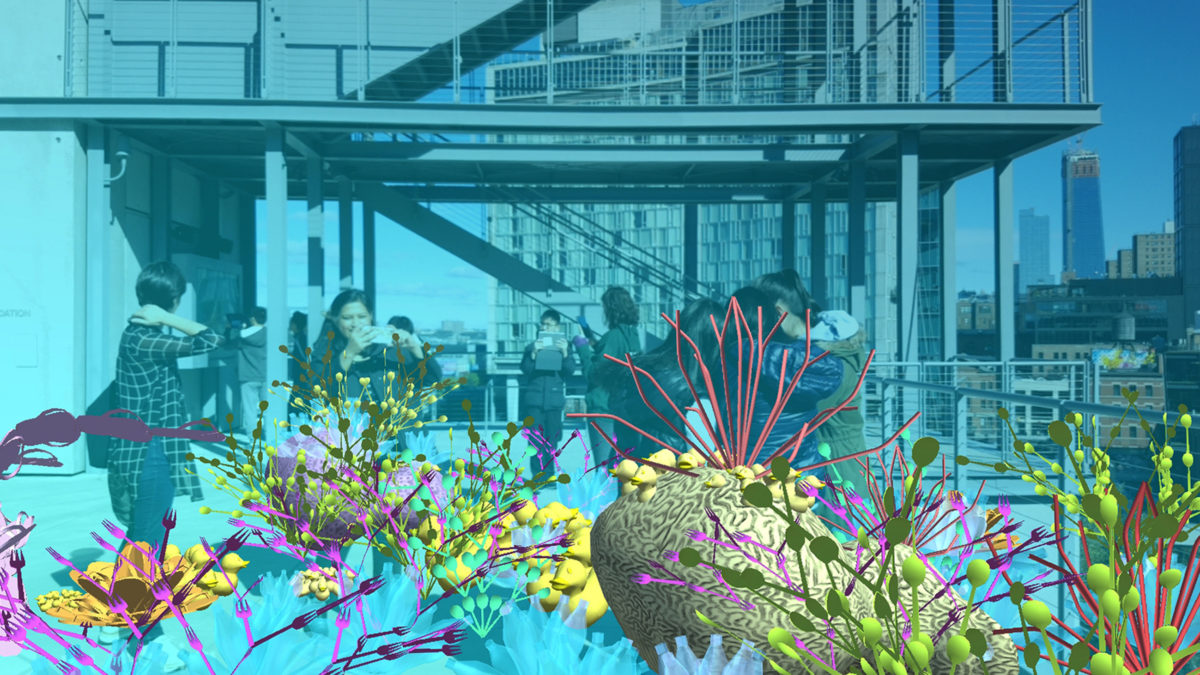

Imagine walking in an urban setting, conjuring a spontaneous rewilding of the world around you; metro stations are dominated by native species, exotic invasives self-seed in parking lots and café patios. Swipe and select a different AR application. This time, the streets are submerged underwater; as both participant and observer, your gaze generates algorithmic patterns of living corals and discarded plastics, existing together in mysterious symbiosis.

These experiences might arise via two augmented reality (AR) artworks by Tamiko Thiel (SM ’83); ReWildAR (2021), and Unexpected Growth (2018), commissioned by the Smithsonian Institution and the Whitney Museum of American Art, respectively, and created in collaboration with the artist /p. Thiel is widely recognized as a pioneer in the field of digital art, and she developed her artistic toolkit as a master’s student at MIT. During that time, she participated in research groups that served as forerunners of the MIT Media Lab: the Architecture Machine Group (founded in 1968 by Nicholas Negroponte) and the Visible Language Workshop (founded in 1973 by Muriel Cooper).

Thiel is fascinated by the interplay of space, place, the body, and cultural identity, and her practice has included envisioning AR experiences, designing virtual reality (VR) installations, and experimenting with machine learning. In 2018, she received a Visionary Pioneer Award for lifetime achievement from the Montreal Society for Arts and Technology, and a retrospective of her practice, “Diverse Realities,” was presented recently at Kunstverein Wolfsburg gallery in Germany. “My artworks are dialogues between the work itself, the viewer or user, and everything they’ve experienced in their lives up to that point,” says Thiel. “Everyone will encounter something different, and that’s the richness of art—it provokes new questions rather than providing answers.”

Engineering and artistry

Having studied engineering at Stanford and working as a product designer at Hewlett Packard, Thiel initially applied to MIT with the intention of strengthening her technical training. During her master’s degree in mechanical engineering, she worked with Professor Derek Rowell to test a sonar-based sensory aid for the blind, as part of research into the localization of sound and the perception of space. “Perhaps that experience activated something in me, because something strange happened when I was leafing through the graduate course catalog between semesters,” she remembers. “When I stumbled across the entries for the Visible Language Workshop and the Architecture Machine Group, all my competing interests suddenly made sense together. I dropped the catalog—from that moment on, I knew I wanted to become a media artist.”

Up to that point, Thiel had sensed a missing link in her education. “I had the instincts of an engineer, but I craved a richer visual world—something that related to the values of my upbringing.” Thiel grew up in Seattle and the city of Kamakura in Japan, surrounded by individuals for whom the connection between the arts and the sciences was a way of life. Her mother Midori Kono Thiel, who is Japanese American, is a prize-winning calligrapher and closely involved with Japanese visual and performing arts. Her father Philip Thiel (SB ‘52) came to MIT in 1950 as a lecturer in naval architecture; his office happened to be located next door to that of György Kepes, who later founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS). “Like me, my father had come to MIT with a feeling that something was lacking in his career. His encounter with Kepes’ ideas about the integration of the arts and the sciences was transformative for him.” Their friendship prompted Thiel’s father to embark on a special bachelor’s degree under Kepes and the notable urban planner Kevin Lynch (BCP ‘47), inspiring him to develop an original system of notation for the spatial perception of pedestrians in urban environments, as described in his book, “People, Paths and Purposes” (Thiel, 1997).

Myth, memory, and mechanics

Studying computer graphics and visual imaging in the context of the Architecture Machine Group and Visible Language Workshop, Thiel gathered the alternative paradigms and techniques she needed to create her own expressive synthesis of art and engineering. Shortly after graduating in 1983, she was employed as the lead product designer on Danny Hillis’ (’78, SM ’81, PhD ’88) Connection Machine CM-1/CM-2, the first commercial artificial intelligence (AI) supercomputer and in 1989 fastest computer in the world—a design which directly influenced the emergence of Google’s AI technology and Steve Jobs’ aesthetic vision for Apple. Thiel designed the computer with translucent panels and dramatic blinking lights, as though to reveal the cerebral processes of a vast electronic brain; she considers the project to be her first professional artwork, and the Connection Machine is now in the collection of MoMA.

“After working on a project like that at the age of 26, I asked myself: what’s left to do?” said Thiel. She decided to move to Germany to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where she had the freedom to investigate the layers of memory, myth, and emotion that form our understanding of familiar places and new spatial environments. Her explorations led to an abiding fascination with revealing the invisible histories and future potentialities latent beneath the surface of perception; she has used VR to reconstruct the experience of living in the shadow of the Berlin Wall, AR to install censored artworks at the Venice Biennale, and “deep fake” neural network technology to expose how easily our own faces can betray us.

Engagement and impact

For Thiel, technologies like AR can help people to access stronger emotional ties to urgent social, political, and ecological issues. “Thinking about what’s going on in the world today, there’s a point when it all just hurts too much,” she says. She recognizes that, for many of us, the response is to retreat into denial or despair.

Her strategy as an artist is to “seduce people into engaging at a deeper level,” by first seeking to enrich their visual worlds. Her artworks allow participants to gain a sensorial understanding of the sliding scale between enrichment and depletion, and each individual’s potential to effect change—as we move through space, we are the ones that have the agency to alter our surroundings, whether by conjuring coral in a digital world, or taking action to preserve ecologies in the physical world. As Thiel writes in her artist statement, “these worlds can now be visible for all those who wish to seek them.”

Written by Matilda Bathurst, Arts at MIT

Editorial direction by Leah Talatinian, Arts at MIT

Photos provided by the artist