On April 30, MIT’s yearlong suite of opportunities for student arts entrepreneurs culminated in the sixth annual Creative Arts Competition, a $15,000 prize for the most promising arts-focused startup at the Institute.

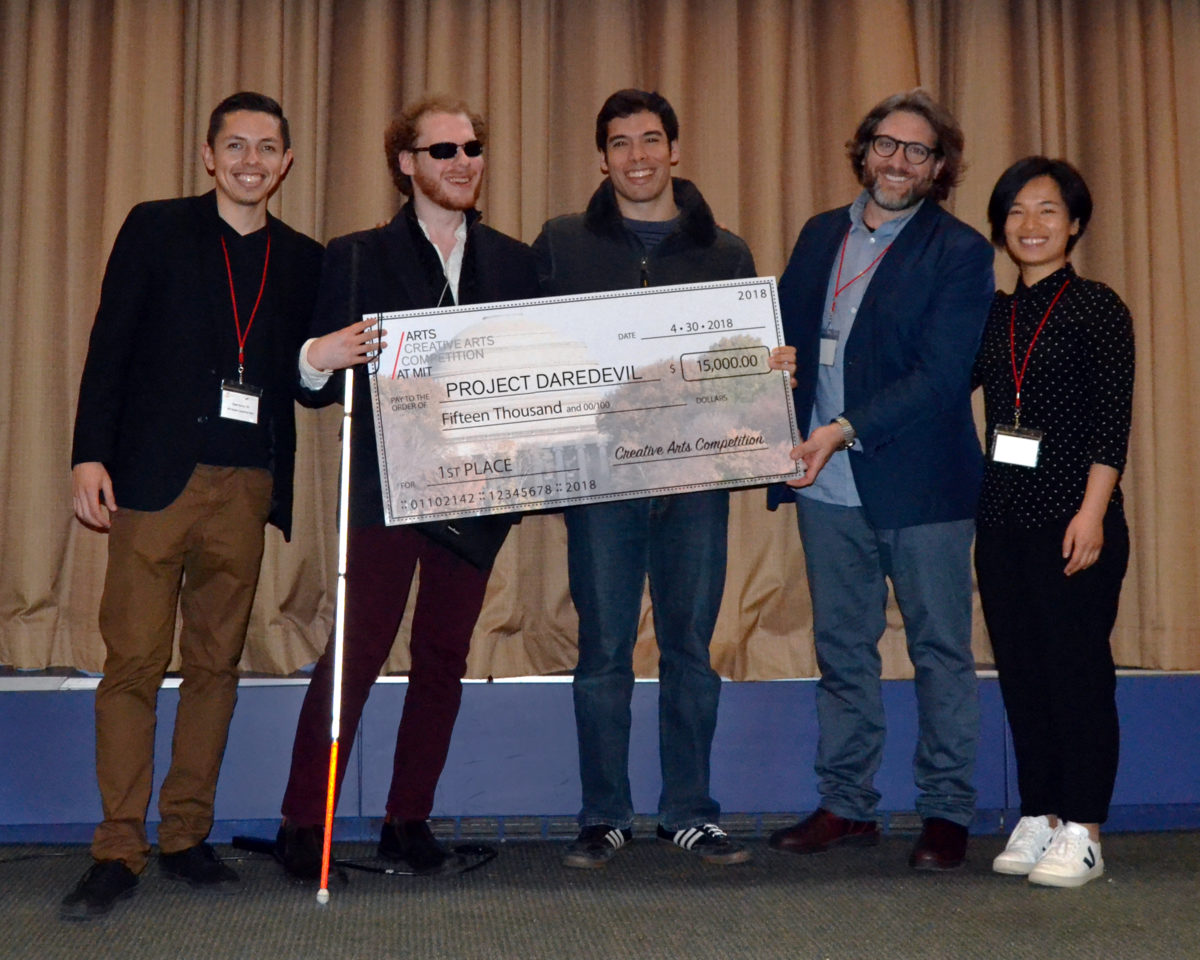

Eight teams were selected as finalists (from 23 applications) to pitch publicly to a panel of judges and an audience of peers and mentors. Project Daredevil (Hapticomix) won first place ($15000). Spaceus was awarded second place ($7500); Helm received third place ($2500); and Piccles took home the Audience Choice Award ($750).

This year’s teams showed marked diversity in business models and missions. “There were teams who want to preserve cultures, like Helm and Kalani; teams who want to build better networks for creative professionals, like Meanwise or Imaginarium of Technology; those engaged in social innovation, like Spaceus; while others are designing apps and artistic technologies, like Piccles or Project Daredevil” says Wenjia Wang, a second year graduate student in the Technology and Policy Program (TPP) and co-organizer of the Creative Arts Competition. “It was a really great mix,” she says, adding, “It was a first for this competition to have the winning team using assistive technology to solve a creative arts problem.”

Edgar Gamino, a first year MBA student at Sloan and co-organizer of the event, says, “What I love about this competition is that it’s not just about providing seed money for one company, or three companies; it’s about creating this ecosystem of arts entrepreneurship and making people aware that this level of creativity, and the support for it, exists at MIT.” He adds, “Generally, a lot of business students stay away from creative endeavors, when they’re looking for what’s called ‘unicorns’ [startups valued at over $1 billion], because these companies seem to exist only in the tech space. But there can be just as much innovation in the artistic space, or in some hybrid of the two, as we see from this year’s finalists.”

THE WINNING TEAMS

Project Daredevil (Hapticomix)

Project Daredevil makes VR for the blind using 3D radio-dramas with motion simulation via a worn vestibular-affecting device. The device imparts accelerations on the head to create sensations of flipping, falling and flying. The technology can be expanded to other markets such as video games, or education, to make experiences more immersive for everyone.

Team members Daniel Levine, an MS candidate in the Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group and a gymnast, and Matthew Shifrin, a sophomore at the New England Conservatory in Contemporary Improvisation with a focus in accordion and classical singing, put it plainly in their pitch: “Media today requires sight.” While entertainment options expand for sighted individuals with the rise of video games and virtual and augmented reality, the 8.4 million people in the US who are blind, including team member Shifrin, have extremely limited access to contemporary media. Shifrin explained how he asks his friends to describe the visuals in action movies, for example, which can be a frustrating process for both parties.

Project Daredevil—named after Shifrin’s favorite childhood comic book superhero, a crime-fighting lawyer who was blinded by a radioactive substance—aims to give the blind full access to comic books in an engaging and interactive manner. The device puts the listener in the center of the action and makes an otherwise inaccessible graphical medium able to be enjoyed by the blind.

Shifrin, who developed the initial concept for this project, is creating the pilot radio-drama based on the first chapter of the Daredevil comic book series; Neil Gaiman is also collaborating with them in future. Levine conceived the initial motion-simulation technology, and is designing and creating the wearable vestibular-affecting device. This technology can eventually be incorporated into traditional goggle-based VR or Video games.

Spaceus

Spaceus transforms vacant storefronts into artists studios, enlivening streets and fostering connections between creatives and neighbors. Team members Ellen Shakespear, a dual-degree candidate (MArch and a Masters of City Planning) in the MIT School of Architecture and Planning, and Stephanie Lee, a Masters student in the MIT Architecture Department, began Spaceus in order to solve three interrelated problems: vacant storefronts due to exorbitant rents, landlords losing out on revenue, and artists working in isolation because they cannot find affordable studio space in many cities.

Spaceus rents shared or dedicated studio space to artists through a subscription-based model. Artists join at the membership level that suits their space and time requirements, and prices vary accordingly, with lower rates for those who only need access on nights and weekends, for example. In order to turn vacant storefronts into beautiful and nimble artist studios, Shakespear and Lee are designing and creating modular furniture, which allows each space to be reconfigured, adapted and replicated easily as they expand to other locations. Their pilot project launches in June in Faneuil Hall, and they plan to expand within Boston and beyond.

Helm

Helm is a wearable low-cost and easy to use 3D scanner that preserves large-scale artworks by taking snapshots of our world. Team members Mitchell Gu and Crystal Wang are both seniors in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. With many cultural heritage sites at risk due to global conflicts, terrorism, erosion or extreme weather, they want to provide unprecedented affordability and ease of use for 3D scanning of artistic heritage sites through modern computer vision technology. With a 360 degree camera mounted to a helmet, art historians, museum curators, or simply concerned citizens can preserve three-dimensional cultural and artistic artifacts simply by walking around or through them while wearing Helm.

The two most common tools used today are laser scanners, which cost over $15K, are cumbersome and complex to operate, and photogrammetry methods (assembling many photos of the subject), which are also expensive, inconvenient and computation-heavy. Helm will test its more accessible, affordable cultural preservation techniques working with the local community in Micronesia at Nan Madol, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, also included on the List of World Heritage in Danger.

Piccles

Piccles is a collaborative coloring application that strives to lower anxiety, relieve boredom and foster connection by engaging people in the cathartic act of coloring. This drawing platform—created by Shakti Shaligram, a student in Integrated Design and Management at MIT; Chris Bent, Abdul Azeem Khan, Sagar Arora and Nelson Everts—lets users make images together. It also enables visual artists to build their following by using their works to create an interactive experience.

Piccles operates on the freemium model with in-app purchases including brushes, colors, and exclusive projects. Users can invite friends to collaborate on images they are working on, leading to organic, social growth. Organizations can pay a recurring subscription for access to upload images, content and advertisements to users. The team also plans to co-market with local hospitals, arts organizations, schools and companies.

BEYOND THE COMPETITION

Among the teams who applied to the Creative Arts Competition, many have a technical focus. “This is something that’s unique to MIT,” says Wang. “We will find a problem and we will solve it with innovative technology.” But she is quick to point out another characteristic of MIT—its diverse student population:

“There are a lot of artistic people here who are also really good at their technical domain. We have great scientists and engineers, but we also have a great architecture and design program, ranked number one, in fact. This mix can generate a lot of ideas, and this competition is a great platform to showcase them.”

The monetary awards are but one aspect to the competition. The Creative Arts Competition is also focused on idea development, mentorship and networking opportunities. Once teams form (which often happens at Hacking Arts in November, or later in the fall), they gain access to the START Studio, a designated makerspace for MIT arts entrepreneurs. There they can develop ideas and attend targeted workshops. Teams are paired with mentors, who coach them over the course of the program. Long after the winners are announced, teams are encouraged to continue to rely on the connections they built with their mentors, as they bring their ideas to impact.

Wang, who competed in the 2017 Creative Arts Competition as a finalist, but who did not place, speaks from experience when she advises all the teams: “Whether or not you win the award, it is probably just an indication of how much progress you’ve made on your business model. Don’t get disheartened by the result. Leverage the connections you make during the competition and use the opportunity to refine your model.” For Gamino, who worked in the arts sector before enrolling in Sloan, he recommends that teams try to bridge the perennial divide between “creatives and suits,” so that “both sides can learn from each other.” He says, “If you can tell the most compelling narrative, while letting the data and the numbers guide your decisions, very cool things can happen.”