Twenty-two years ago Nicholas Negroponte, MIT Media Lab co-founder, predicted that “being digital” would lead to a future with fewer material constraints. “Being Material,” the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology’s second biennial international symposium, used Negroponte’s Being Digital as a touchstone to explore the current, and sometimes unexpected, convergence of the digital and material worlds across disciplines. Organized around four sessions and a concert—Programmable, Wearable, Livable, Invisible and Audible—the symposium showcased recent developments in materials systems and design, placing this work in dialogue with kindred and contrasting philosophy, art practice and critique.

Negroponte opened the two-day event with “Been Digital,” a reflection on his pioneering work in the MIT Media Lab and the future scenarios he anticipates, in which biotechnology will be the “new digital.” Indeed, many of the panelists’ work in this domain supports Negroponte’s prediction, including synthetic biologist Tal Danino’s research into programming bacteria to detect cancer cells and biologist and artist Christina Agapakis’s bioart objects, like cheese made from bacteria found on the human body (specifically, in Olafur Eliasson’s tears and on Hans Ulrich Obrist’s nose).

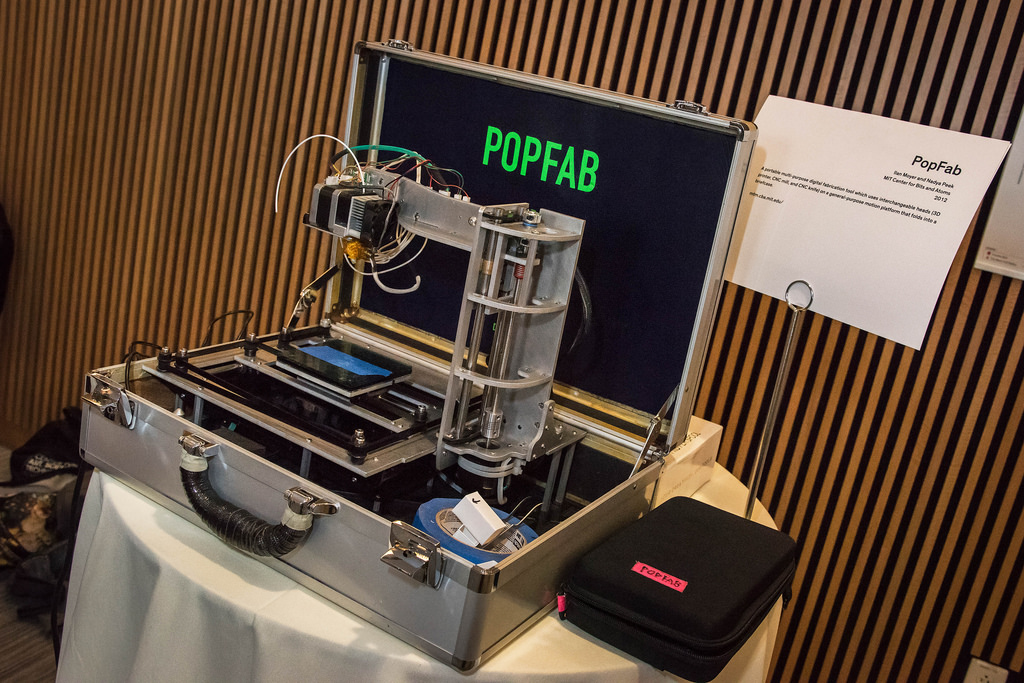

Co-convener of the symposium and founder of the MIT Self-Assembly Lab Skylar Tibbits, Assistant Professor of Design Research in the Department of Architecture, MIT, expanded on Negroponte’s forecast to include work in such materials as fluids, textiles, wood, plastic and foam, which he believes will shape the future of design along with biotechnology. Tibbits claims that, “Physical materials are not just responding to digital properties. They are not just something we make through digital fabrication; they have digital properties embedded in them. We can now program them just like we did computers and machines. Yesterday we programmed computers and machines, but I believe today we are programming matter itself.” Many of the speakers demonstrated through their work that computation is not being imposed on matter. Rather, as MIT researcher Nadya Peek pointed out, “we discovered computation as much as we invented it.”

In addition to examining how materiality has reasserted itself since the digital revolution and how the digital-material divide is porous at best, the speakers also addressed the broader social, environmental and political ramifications of their work. “One of the lessons we learned [at the symposium] is that our machines have people inside them—social relations and economic relations are built into the technologies that we create even when those are at scales we cannot see. So, programmable matter, even at the nanoscale, is something that has to be thought of sociologically, culturally and politically,” says Stefan Helmreich, Elting E. Morison Professor of Anthropology and Program Head, MIT, and co-convener.

These humanistic concerns were a dominant theme in all four sessions. The Programmable session examined the democratization of technology—whether working with less costly, ubiquitous materials (for greater access globally, like Manu Prakash’s folding microscope), or designing computer programs like Casey Raes and Ben Fry’s Processing to liberate creators from the whims of market-driven software manufacturers. The Wearable panel looked at the intersection of the digital and material as it pertains to the body, including developments in fashion design, such as the use of reactive and electronic textiles in Hussein Chalayan’s collections; in portable devices, such as webcams, backpack cameras or fitbits; and in provocative projects like artist Lucy McRae’s ingestible perfume that allows the user to sweat fragrance. The Livable panel reflected on “the earthly and often unintended consequences of human structures of design, as well as the material conditions of social inequality as they are produced in the context of war, resource extraction and displacement,” according to its moderator Bettina Stoetzer. The Invisible panel investigated the politics of what is seen—what governs what we see or don’t see given the technologies of cloaking, surveillance, data capture and machine vision.

The commingling of bits and atoms has implications for every facet of life, including artistic discourse and art objects themselves. The artists who spoke at the symposium work in a wide range of materials and fabrication techniques, but all commented on how this merger of the digital and physical realms impacts their work. Trevor Paglen spoke about what he considers a “paradigmatic transformation” in our culture—the emergence of images made by and for machines and technologies of nonhuman machine vision. Paglen explains, “[Machines] see in profoundly different ways than we see,” able to mine trillions of images with profound efficiency. On the other end of the spectrum, artists like Agapakis design “custom microbes”—work that aligns with Tibbits’s view that we are seeing “pure materials that have these amazing capabilities that we haven’t seen before—elegant solutions that aren’t robotic, device-heavy computers or ‘smart’ objects,” that change our notion of what is digital.

In many ways, we are still at the beginning of discovering the digital properties and potential within our material world, and as Negroponte and Tibbits predict, discoveries in biotechnology and materials science will play a large role in shaping the future.

This article, “The Convergence of Bits and Atoms,” originally appeared on the VoCA blog on June 9,2017.