Tomás Saraceno: Arachnid Orchestra. Jam Sessions

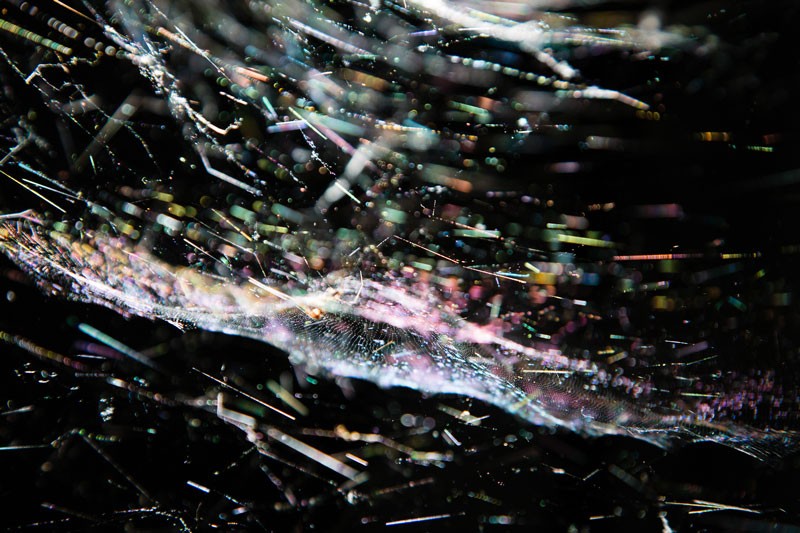

Arachnid Orchestra. Jam Sessions, on view from October 23, 2015 to December 20, 2015 at Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, is a new production by CAST Visiting Artist Tomás Saraceno that brings his long-term research on spider webs into the realm of sound. Saraceno uses spiders’ sophisticated mode of communication through vibrations and the incredible structural properties of spider silk to elevate webs into musical instruments. Arachnid Orchestra. Jam Sessions is an interactive sound and visual installation, a process-driven laboratory for experimentation that pushes the boundaries of interspecies communication.

MIT Professor Stefan Helmreich’s “Spider DJs” appears in the catalogue for Saraceno’s Arachnid Orchestra. Jam Sessions. Below is an excerpt from his essay.

From “Spider DJs”

In 1973, anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously offered that, “Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun,” continuing on to suggest that we might “take culture to be those webs.”1 Impossibly extracting ourselves for a moment from the sticky tangle of gender specificity and neutrality uneasily marked by the word “Man,” we could say, following anthropologist Matthew C. Watson, that Geertz’s metaphor makes people into spiders and anthropology into arthropology.2

Tomás Saraceno’s Arachnid Orchestra weaves such anthropology and arthropology together, proposing webs of sonic significance that crosswire human and spider beings. The orchestral analogy animating Saraceno’s piece, which has orb-weaving spiders from genera Nephilia and Cyrtophora serving as string players and members of the families Lycosidae and Sparassidae playing percussion, translates a 16th and 17th century European musical and cultural practice into a webworked invertebrate idiom—with ballooning spiders, who activate an Aeolic Theremin-inspired instrument, extending the analogy into the terrain of the mid- twentieth century aelectrosonic.3 The Arachnid Orchestra is thus a record of what happens when one tradition of human musical aspiration is transposed into a different species key. If, as Hugh Raffles writes, “Vibration is the currency of the web-dwellers. Mimicry is their method,” that mimicry is here piloted into a cross- species anthroarachnosonic.4

About the author

Stefan Helmreich is Professor of Anthropology at MIT. He is the author of Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas (University of California Press, 2009) and, most recently, of Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond (Princeton University Press, 2016). His essays have appeared in Critical Inquiry, Representations, American Anthropologist, and The Wire.

Arachnid Orchestra. Jam Sessions is curated by Ute Meta Bauer, Founding Director and Anca Rujoiu, Curator, Exhibitions.