It is often said that Morton Feldman’s “String Quartet II” is an experiment in scale. That is a fancy way of saying that the piece is very, very long—approximately six hours. The players—perhaps better described as marathoners—cannot eat or relieve themselves throughout the duration. As a result, “String Quartet II” has acquired a reputation of almost mythical proportions. In 1996, the Kronos Quartet famously cancelled a performance, citing, as reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, “serious physical side effects.” Like the frozen bodies that litter Mt. Everest’s heaving sides, the specter of that long-ago failure is preserved in perpetuity.

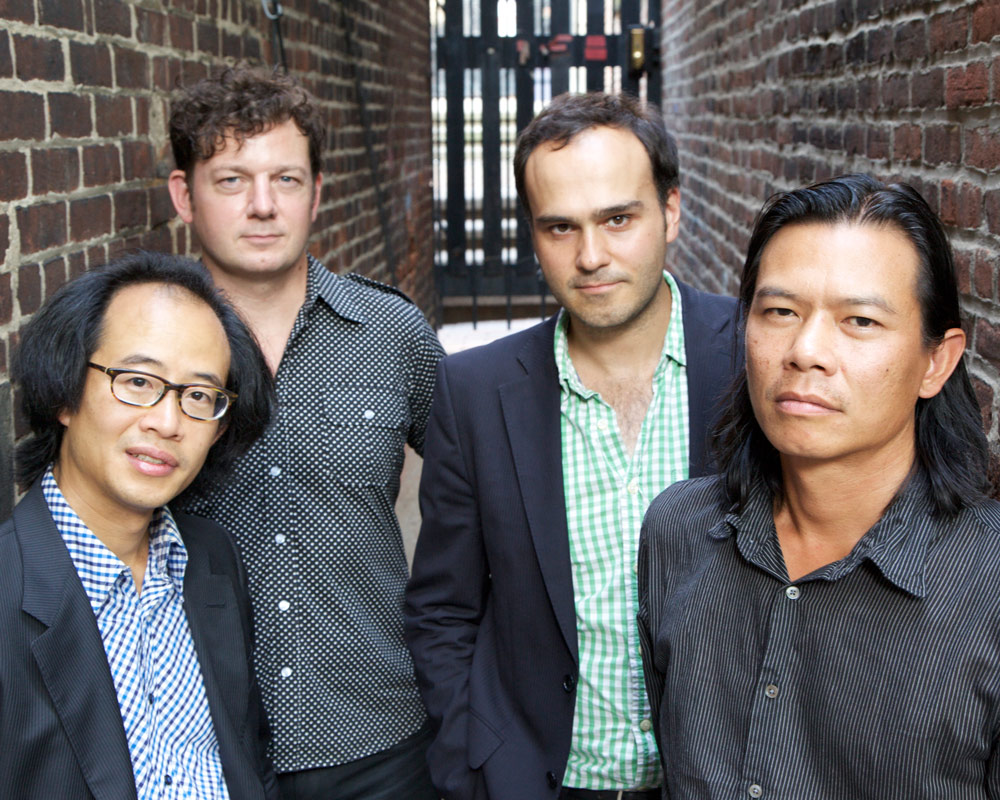

In the years since, “String Quartet II” has been tugged a little closer to earth. New York City’s FLUX Quartet first tackled the piece in 1996 and have completed a total of (always successful) 12 performances. They will clock their thirteenth on Feb. 28 at MIT’s Killian Hall as part of the MIT Sounding series. The concert will also mark the Boston premiere of Feldman’s infamous quartet.

“It’s almost like a practical joke, right? Sometimes we feel that way,” says FLUX Quartet violinist and founder Tom Chiu of the overwhelming length of the Feldman Second. “Even if some people think of it as a gimmick, at the very worst it came from a place where Feldman wanted to bust out of that traditional 30, 35-minute piece. I don’t think he’s wrong: if you write something that’s just 10 minutes longer than that, it doesn’t really accomplish what you want it to accomplish.”

So what was Feldman trying to accomplish? He wrote “String Quartet II” in 1983, but the essence of his artistry can be traced to the 1950s and his friendship with John Cage. Like Cage, Feldman was thoroughly avant-garde in his philosophical approach to composition. Unlike Cage, he was less interested in completely exploding the notion of what music can be—four minutes and 33 seconds of silence, for example, or a dead fish slapped against piano strings—so much as extending the existing parameters of music to their outermost limits. “String Quartet II” is excruciatingly long, yes, but it is also excruciatingly lovely, a dewy, shifting fog where dissonance slides in and out of focus and harmony breaks fleetingly, like blue sky through wafting clouds. The point is not to make musicians miserable, but to produce a meditative state. The point is not to make audiences bored, but to conjure an exquisite sonic mist upon which their stray thoughts may drift. It’s easy to imagine that “String Quartet II” strives to speak in the language of the Ents in Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, tree-beasts who experience time on such a massive scale that they think nothing of taking several hours to say “hello” but possess wisdom beyond what puny humans can comprehend.

“String Quartet II” is composed of cycling musical cells, each only slightly different from the last, and each repeating a seemingly random number of times: nine, eight, 13. The piece requires that players retain relentless focus in order to keep track of repeating measures, and also that they remain almost impossibly quiet. “You get into this transfixing sort of haze,” says Chiu. “I almost liken it to an electronic sound installation. It sounds like a museum piece. It sounds like an art installation as much as it does a piece of music.”

Appropriately, the MIT concert will be something like a performance/exhibit hybrid. “Everyone comes from different experiences, different amounts of exposure to this type of music,” says Chiu. “So we try to set up … a space that allows people to experience it with the utmost degree of freedom. We’re likely going to be situated in the middle of the room, with the audience around us. And people can come and go.”

One of the most challenging aspects of “String Quartet II” is its softness. Playing quietly for that long, says Chiu, is surprisingly strenuous. “We’re trained to be in action, we’re not trained to be suspended. And I think the feeling, physically and aesthetically in this piece, is suspension,” he says. Again, physical arduousness is a means to an end—a sense of weightlessness, of extending, almost indefinitely, the moment between inhale and exhale.

But, says Chiu, the biggest challenge is mental. “We definitely space out, zone out. All these terms apply,” he says, laughing.

“At the outset of the piece—30 minutes in, 60 minutes in, 90 minutes in—there’s easier human control over that,” Chiu explains. “But as the piece gets longer and longer, you start to lose control of that. You just go with the moment, whatever the moment is.”

And that may very well be the essence of “String Quartet II,” for players and audiences alike. “It’s very much like you’re inside the music rather than outside of it,” says Chiu. “String Quartet II” speaks quietly, forcing the listener to lean in, to commune as close to the music as possible.

“There are surprises in the latter three hours of the piece,” says Chiu. “And both as a player and as a listener, for those that stay for the whole time, you realize, ‘Oh this has been all worth it. We’ve arrived at this completely gorgeous spot.’”

For his part, Chiu hopes that people will be enticed to stay longer than they had planned. “I think everyone who’s experienced it [has] left with some level wonderment.”

Concert details: Sunday, February 28, 2016 from 2-8 PM in 14W, MIT Killian Hall

Tickets: Eventbrite