“In our increasingly complex society, science and technology can no longer be segregated from their human and social consequences. The most difficult and complicated problems confronting our generation are in the field of the humanities and social sciences.” This declaration, written in 1949 by the Lewis committee in their “Report on the Committee on Educational Survey,” represents a pivotal point in MIT history when scientists and engineers sought to elevate the humanities within the Institute in response to world events. Efforts to integrate the arts and humanities into the curriculum at MIT have existed since the Institute’s founding in 1861. While every major shift in academic policy bears the hallmarks of its time, one constant is that MIT leadership makes changes in response to larger forces at work in the world. The arts and humanities are championed most in times of historic or cultural urgency. Examining why the arts and humanities have been included in MIT’s educational program may shed light on the contemporary STEAM movement, especially the arguments in favor of STEAM posed by those in STEM.

The devastation caused by World War II deeply troubled men like MIT professor Warren K. Lewis, who had worked on the Manhattan Project. In 1947, Lewis, the father of modern chemical engineering, chaired a committee to determine whether the principles of education that had guided MIT academic policy for nearly 90 years were still “applicable to the conditions of a new era emerging from social upheaval and the disasters of war.” By the 1940s, MIT’s founding principle, “‘Learning by doing’ began to be interpreted in its narrowest and most utilitarian sense,” the Lewis committee lamented. They sought to correct this over-emphasis on technical training by establishing the School of Humanities and Social Sciences.

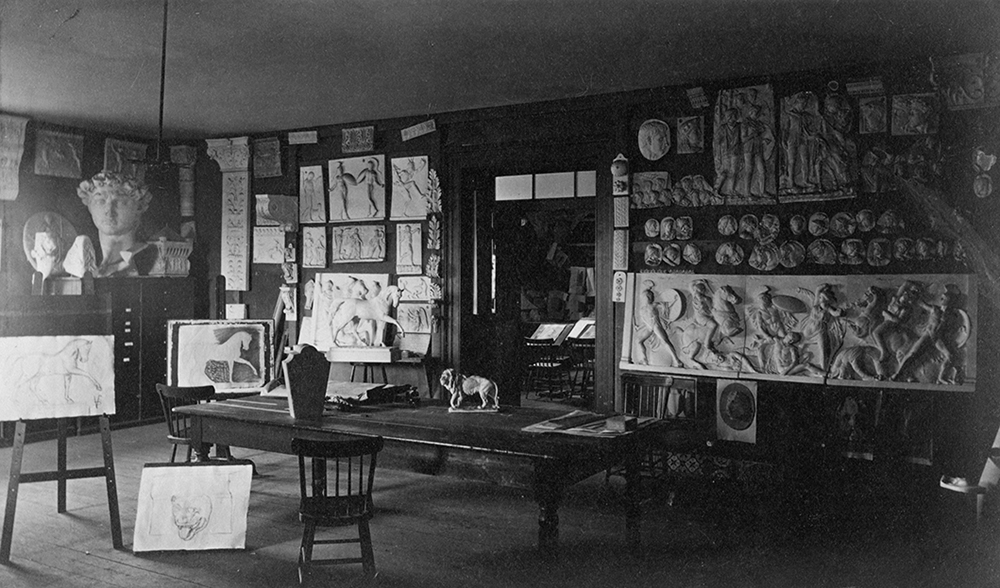

In some ways, this shift in educational policy recaptured the broader mission that the Institute’s founder William Barton Rogers envisioned. When Rogers founded MIT in 1861, he intended for the Institute to have “the triple organization of a Society of Arts, a Museum or Conservatory of Arts, and a School of Industrial Science and Art.” This larger agenda was unrealized, but the arts played a part in the science and technical institution nonetheless. For example, William Ware, who founded the first architecture program in the country at MIT in 1866, insisted on a curriculum that incorporated the history of architecture and ornament and rigorous training in mechanical and freehand drawing, as was typical of a Beaux-Arts education. Many musical ensembles and an orchestra also enriched MIT in the 19th century, but these groups operated outside the curricular structure. The Lewis committee not only reaffirmed this 19th century model, they also reshaped the MIT education for the atomic age, expanding it to “boldly undertake new experiments in education and new explorations into the unknown.”

The arts gained prominence throughout the 1950s. The Hayden Gallery (renamed the List Visual Arts Center in 1985) opened in 1950 and in its first year mounted ambitious exhibitions like “The Paintings of Georges Braque,” as well as two exhibitions originating at the Institute, “Edgerton Stroboscopic Photography” and “Visual Education for Architects,” which traveled to other museums in the United States. In 1952, John Burchard, Dean of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, commissioned “Art Education for Scientist and Engineer.” Similar to the Lewis Report in its aim to broaden MIT education, this document focused specifically on the visual arts. It was written between 1952 and 1954 by museum directors and members of 19 university art departments, who proposed a sequence of courses that integrated history and studio exercises and emphasized artistic work that illustrated the connections between art and engineering, such as the experimental works of designers Moholy-Nagy and Buckminster Fuller. They also acknowledged similarities between art and science, “both products of analysis and synthesis, of intuition and a judicious perception of order.” The recommendation outlined in this report was to add the arts to the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, where they could best serve the entire student population without becoming absorbed into the professional curriculum in the School of Architecture.

The 1954 President’s Report perhaps hints at why the arts began to matter more during the Cold War period against the backdrop of nuclear armament: “If American science is to continue to prosper, if it is to continue to attract to it its proper complement of creative and gifted minds, we must everywhere combat the mistaken notion that science and engineering are narrow, provincial and destructive of human values. We must demonstrate instead that science and engineering are great liberalizing, humanizing forces as well as the greatest intellectual structure achieved by our civilization….” The fine arts had “its ups and downs” that year, according to the report, because the administration strategically focused more resources on music, since that program was on more solid footing. The Institute was, however, poised to “include laboratory instruction in visual design as one of the upper-class elective sequences.” Its purpose would not be to offer “conventional courses in painting or sculpture,” nor “to produce amateur artists,” but to contribute “something much more profound…related to the experiences in the Bauhaus, the work of Moholy-Nagy in Chicago and more recently that of Professors Gyorgy Kepes and Richard Filipowski in our own School of Architecture.”

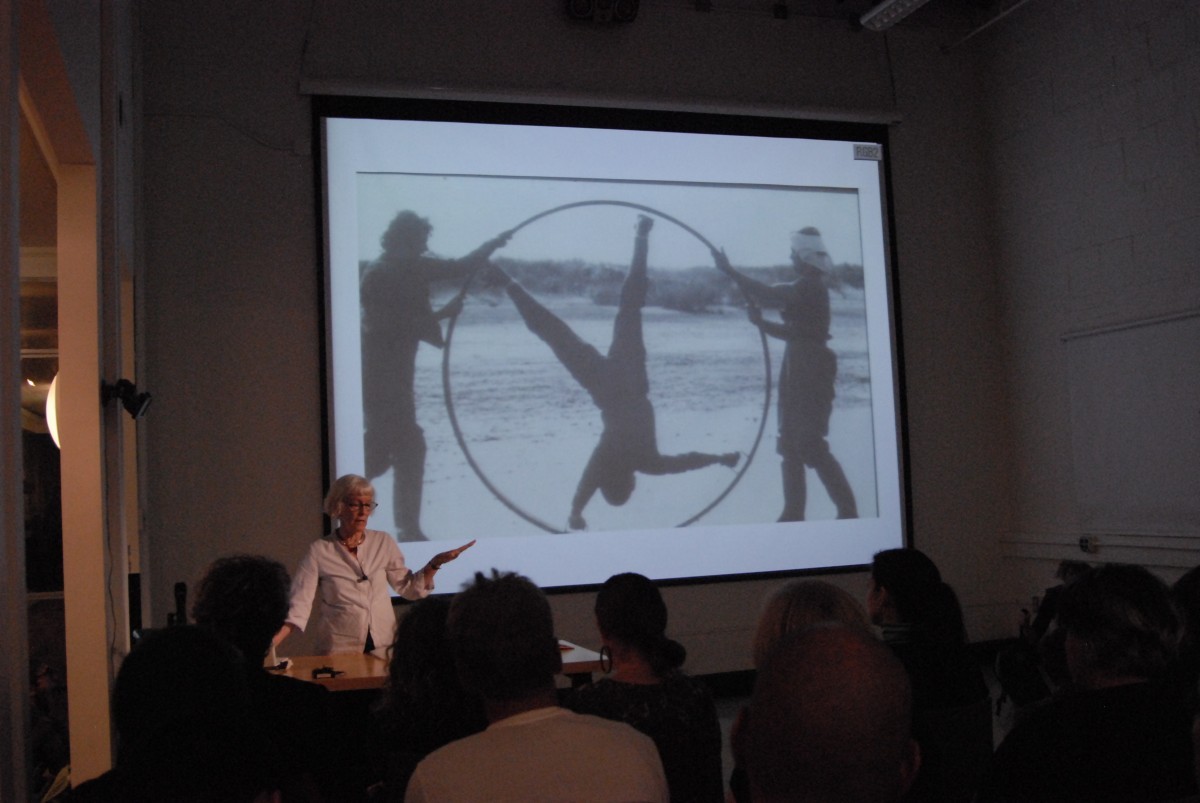

After teaching at MIT for 20 years, Kepes became the first director of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) within the School of Architecture and Planning—a watershed moment for the arts at MIT. With the creation of CAVS in 1967, artist-fellows of international acclaim working in film, light and kinetic sculpture, or with computers and electronics, were appointed to develop new experimental work, often in collaboration with faculty across the Institute. Major cultural and technological shifts in the late 1960s led to similar boundary-crossing in the curriculum. And what is more, the science core requirements were cut in half, which gave students a great deal more flexibility in their schedules to pursue arts-focused or interdisciplinary subjects.

In the 1967 President’s Report, the MIT School of Engineering describes a “seemingly insatiable demand for computer resources” and “a rapidly mushrooming involvement of students and faculty in new areas of research which cut broadly across previously defined disciplinary boundaries.” Nicholas Negroponte, who had done his doctoral work under the supervision of Kepes, founded The Architecture Machine group in 1967, which granted master’s and doctoral degrees; it was intentionally multidisciplinary, with an equal number of students coming from architecture and electrical engineering. At this time, the Stroboscopic Light Laboratory was expanding on work it had begun during World War II to develop techniques for high-speed cameras, the use of sonar for archaeology, the use of elapsed-time underwater cameras, a plankton camera and elapsed-time motion picture films, which had applications in many fields. Also in the late 1960s, Richard (“Ricky”) Leacock and Edward Pincus formed the Film Section (later Film and Video) in the School of Architecture and Planning.

In this period, the administration aspired to strengthen the arts and humanities, “not only to provide the framework to understand and direct the goals of science,” but also because these disciplines “are important ‘in and of themselves,’” as outlined in the 1967 President’s Report. With the arts and humanities valued in their own right, the mutual benefit of crossing disciplinary boundaries is newly recognized (in the 1967 President’s Report): “Just as science and engineering students need the breadth of humanities and arts, so could the humanities major of the future profit immensely by the addition of strong science in his course of study. The further promise of this relationship at a wholly new level is clear, but how we achieve this we are not yet sure.”

That argument, however, did not diminish the longstanding idea that the arts humanize science. Just as the Lewis committee noted that “the impact of science and technology on society” is a great challenge for humanists, Provost Jerome B. Weisner says in the 1967 President’s Report:

“As the scale of technical capabilities grows and becomes ever more pervasive and as MIT’s faculty turns to an active involvement with the large social problems of society, urban development, nation-building, health care, environmental control and more effective education, we must constantly be reminded that we build for man; we must constantly strive to understand what this means…. The presence of creative, humanistic scholars and artists probing the objectives of society, remembering the lonely human being, relating to the past and questioning the future, emphasizing the moral and esthetic and respecting the intuitive will insure that our great social engineering efforts reflect the best possible perception of man’s real needs.”

By 1970, when Bartlett H. Hayes, Jr., of the Addison Gallery at Phillips Academy in Andover surveyed the arts again to imagine their future role at MIT, a consensus emerged. The arts would promote a sense of discovery and open-ended inquiry. Also, Rogers’s founding belief, which was affirmed by the Lewis Committee, was upheld again—the arts and humanities would encourage engineers to address the “total culture” rather than a narrow technical audience.

By the mid-1970s, the scope of the arts at MIT had broadened considerably to include the visual arts and explorations in music, media, and performance. The Studio for Experimental Music, set up by Barry Vercoe in 1973 and the Visible Language Workshop created by Muriel Cooper and Ron MacNeil in 1975 joined with Negroponte’s Architecture Machine Group and other units to form the Media Lab in 1985. This new design and research unit explored interactive systems for computational graphics, film, music, narrative, and performance; today it is comprised of 27 “anti-disciplinary” groups, investigating everything from personal robots to new forms of expression to synthetic neurobiology.

Former provost John Deutsch said in 1999, “We are faced not with disciplines, but situations.” From the Lewis report onward, this is a constant refrain. Today, academic programs in the arts exist in both the School of Architecture and Planning (SA+P) and the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (“Arts” was added to the name of the school in 2000). Since 2009, students have been required to take a least one subject in each of the three HASS categories—arts, humanities, and social sciences. “Over time, the changes in the world forced MIT to have a broader educational vision. Adding the arts to the HASS requirement puts the arts on the undergraduate map in a way that it never was before,” says MIT Professor Rosalind Williams, who was the first Dean of Undergraduate Studies and Student Life. Also in 2009, the Visual Arts Program (VAP), created in the Department of Architecture in 1989, merged with the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS). These united academic and research units were renamed the program in Art, Culture and Technology (ACT). Not an art school in the traditional sense, the program’s mission is to promote the interplay between science, technology, art, and design and to deploy artistic practice as a research methodology. Undergraduate students can major or minor in ACT, and the program also awards graduate degrees.

In 2012, another cross-disciplinary research unit was established, the Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST). CAST promotes research, teaching and programming at the intersections of art, science, and engineering. The Center brings renowned artists to campus as co-creators with faculty and students and sponsors international symposia focused on areas of deep, longstanding, or rapidly advancing research at MIT in various domains of the arts and sciences. Since its inception, CAST has provided 116 grants for more than 80 artist residencies and collaborative projects with MIT faculty and students, 33 cross-disciplinary courses, three concert series, and numerous multimedia projects, lectures, workshops, and symposia. “Today the Institute is building on its strengths in collaborative research to tackle problems greater than any single discipline can resolve and find solutions unimaginable without transdisciplinary morphing,” says CAST Executive Director, Leila Kinney in the 2011 report, “Arts at MIT White Paper.”

In recent years, the trend has been toward greater flexibility in the curriculum and ever more boundary crossing among disciplines. By double majoring or minoring in new interdisciplinary fields, it is possible for undergraduates to merge engineering subjects with electronic music, or computer science with virtual storytelling or theater, or synthetic biology with visual art, for example. Jake Gunter, a 2017 graduate in the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences and the School of Engineering, points out how computer science, for instance, “might be the field most ripe for applications in artistic fields” since theater, music, visual art, have all been computerized. “It’s possible, in a lot of ways that you might not expect immediately, to merge your artistic interests with your technological, engineering, or science interests,” he says.