“Be stubborn and ultimately believe in your writing,” advises first-time novelist Mia Heavener ’00, “especially if you are having crappy writing days.”

On April 13, Heavener visited Wyn Kelley’s literature course “Reading Fiction: Voyages” to share her story of writing Under Nushagak Bluff (Red Hen Press, 2019). Conducted via Zoom, the class engaged a group of eager MIT students. “Holy moly,” says Heavener, “I was so impressed by the depth of their insights.” Her visit was supported by the Council for the Arts at MIT through its recently established Artist Guest Speaker Program.

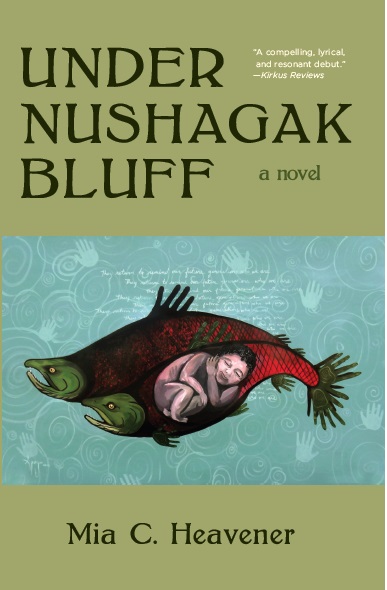

Set against the backdrop of commercial fishing in an Alaskan Native village, the novel traces one bloodline of Alaskan women struggling to make a home for themselves. Heavener, of Yup’ik heritage, drew deeply on her own experience in rural Alaska, where each summer she works with her family’s commercial fishing business in Bristol Bay.

“I wanted my students to engage with someone like her,” says Kelley, “an MIT alum who combines her engineering training with fiction writing in a powerful way. Someone who is authentic, and who writes with the persistence of an MIT problem solver.”

Starting Out

Heavener and Kelley’s relationship goes back a couple decades. In the ’90s, Heavener sat in the back of Kelley’s “Voyages” class and said very little.

“I remember being totally scared of you,” says Heavener on Zoom. She giggles. “Now that I think about it, that’s actually funny.”

“I think what you were scared of was Henry James,” laughs Kelley.

Kelley didn’t know at the time that Heavener was writing fiction, until one day Prof. Ilona Karmel, whose office was next to hers, told her that Mia was really special and to watch out for her. “I began to pay more attention and to find in Mia an utterly fresh perspective that came from her being Alaskan, a part-time fisherman, and a member of a family steeped in a troubling history.”

“She’s tougher than she looks. She has to be.”

It was Karmel who had the most profound impact on Heavener’s writing, starting with a freshman seminar. They were a small group who wrote short pieces to discuss, and then met one-on-one with Karmel. “She cracked me up because she was so blunt,” says Heavener. “After the seminar, we would meet quite often to go over my writing. Once she took me to the Coop and bought some short stories of Chekhov for me. ‘You have to read Chekhov if you want to write,’ she said. I still have some of her written comments. I had the sense she really believed in my writing.”

“One time when I was visiting Ilona I asked her how long it took her to write An Estate of Memory, and she said ten years. I asked her why it took so long, and she said, ‘I’ve been working.’ It’s funny looking back on it now, because Under Nush bloody took that long for me too. If I could, I’d tell her, ‘Ok, ok, you’re right Ilona. Of course.’”

After Karmel died in 2000, Kelley offered herself as a willing ear to Heavener, who was working in an engineering firm nearby. Kelley met with her weekly for a year or so, as Heavener struggled to finish her novel Tundra Berries, which is still unpublished. It also takes place in a remote Alaskan fishing village. “Most of what I wrote back then was set in Alaska,” says Heavener. “I think I was feeling homesick, plus I had the distance to create whole worlds.”

Heading Home

Heavener still feels strongly connected to MIT. “I come back to bug Wyn at least once a year,” she says. “As a writer from MIT, or as a writer who is also an engineer, I think I have a different sort of journey.” She says it’s always been important for her to do work for the public good. As a civil engineer, she helps design water and wastewater systems in Alaskan Native villages.

“And I think that has allowed me to write with less guilt,” says Heavener. “Writing to me is partly selfish. It’s a way to make sense of my world. There is so much to learn about others through stories. It’s an important part of being human.”

Heavener feels the biggest influence on her writing has been commercial fishing. “Hard labor outside with family is great for reflection. Fishing taught me a work ethic and how to push through when I was tired, cold, wet, and hungry.”

On Zoom, she tells Kelley’s class, “You can’t be too linear with your writing, like, ‘I’m going to list this out and make it work.'” She explains how she wrote some fiction on her own at MIT, but without an official major or minor. “You just have to let a story sit with you.”

“Over time, I’ve learned to separate my writing life from my engineering life,” she says. “I was very determined to do both.” Her dad was a civil engineer who died when she was 11. A couple months later, she decided that’s what she wanted to do as well.

But she found her first engineering job “boring as hell, like sizing bolts or something. I was so miserable.” She decided to go to Colorado State to study writing, earning an MFA in 2007, before heading home to Alaska to work on her novel and at the same time use her engineering skills to help out native communities.

In Kelley’s class, student Sebastian Perez asks,” What are some of the things that got left on the cutting room floor? What are some of the unfinished, unrealized ideas that are not in the final version?”

Heavener answers with a sense of the long hard work of novel-writing. “There were several characters I cut out, a lot of scenes. I think I cut 100,000 words. One of the initial readers basically told me that there’s enough in the village to carry the story.”

—

Mia Heavener is currently a writer in residence at Alaska Pacific University. She is a Senior Civil Engineer with Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. Her stories have been published in “Smokelong Quarterly,” “Willow Springs,” and “Cortland Review.”

Written by Gary Duehr