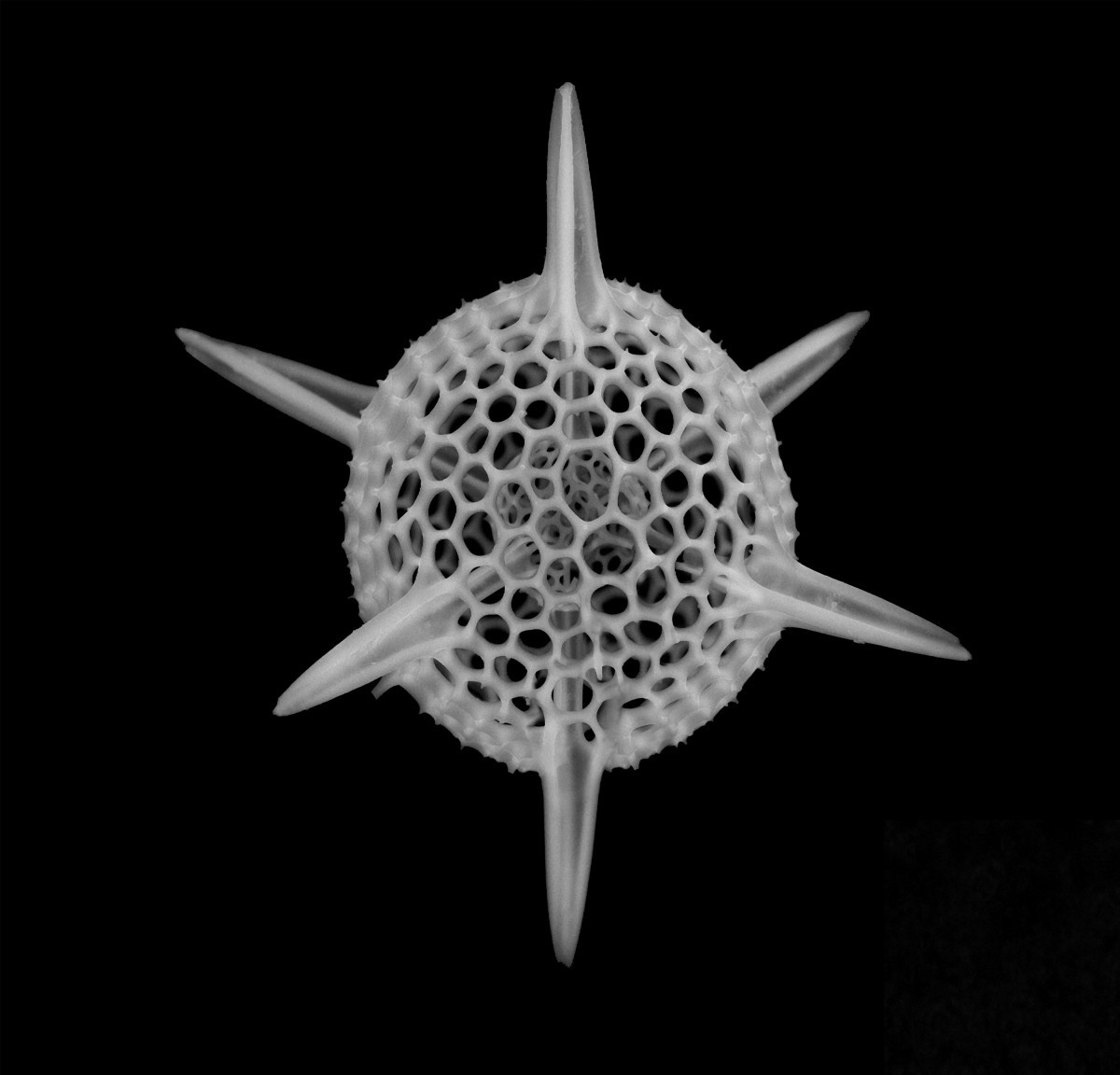

Radiolaria are microscopic protozoa that float through the ocean, smaller than specks of dust. They look like futuristic spiked orbs, slender thistles protruding from intricate exoskeletons. They get their name from the Latin, radiolus, or little sunbeam, and were most notably depicted by the scientific illustrator Ernst Haeckel’s Art Forms from the Ocean: The Radiolarian Atlas of 1862. Their skeletons litter the ocean floor, providing records of geologic periods from long ago. But at thirty microns — about a quarter of the scale of a single strand of human hair — the beauty of these tiny single-celled organisms is largely unknown to us.

“People don’t know this invisible world exists around them,” says Prashant Patil, a doctoral candidate in the Media Lab’s Center for Bits and Atoms, an interdisciplinary initiative exploring the boundary between computer science and physical science. In this lab, Patil, whose background is in physics and electrical engineering, works with an assortment of electron microscopes that reveal a window into the world of the very small, those forms of life invisible to the naked eye. At the Center, Patil says, he “enjoys thinking about what these microscopes can do beyond their intended applications.”

One of these applications is creating art. Patil is now collaborating with photographer Michael Benson, renowned for his composite photographs of the galaxies created from scientific data sets, to use microscope electron photography to document the landscapes of the infinitesimal. The collaboration will result in a book, Nanocosmos, published by Abrams press and partly funded by the Council for the Arts at MIT.

“My personal inspiration came from the Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci,” Patil says, “I was fascinated by him since childhood, when I first read about him in my high school history textbook. He is well-known for his artwork but he was also an engineer and inventor. He used his engineering skills to present art in ways no one even imagined before. With this project, I am trying to do the same: to use what I have learned being a scientist and use MIT’s state-of-the art facilities to create novel art forms.”

Throughout the course of the history of art, new forms of art have emerged in response to evolving technologies — instruments that often enhance or alter individual perception, providing a means to see from different perspectives and scales, from the wide expanses of the universe to the smallest bacteria cell. While the optical microscope is now widespread — familiar to anyone from grade school science classes — the types of microscopes in Patil’s lab, which use electrons and not photons to record phenomenon, are less well-known. These include microscopes such as scanning tunneling microscopes that can move atoms from one location to another, or focus ion beam systems that can etch patterns (which Patil used to write his name on a radiolarian to send to his girlfriend in Mumbai).

Patil is excited by the prospect of working with an artist to raise awareness about this invisible life. “I’m an engineering and science guy,” he says, “I don’t know how to present something artistically so people care about it.” But that will soon change. After imaging these tiny organisms, Patil and Benson will use the Center’s advanced digital fabrication tools to create life-size replicas of the microscopic radiolaria for everyone to see and enjoy.