Sara Laura Wilson, a third-year PhD student in Mechanical Engineering, believes that the arts can spark meaningful discourse on climate change, a problem space typically dominated by scientific research. To bridge this gap, Sara, alongside Marwa AlAlawi, a fourth-year PhD student in Mechanical Engineering, and Supreetha Krishnan, a Media Assistant at MIT’s Art, Culture, and Technology program, collaborated on Interwoven: The Interdisciplinarity of Sustainability at MIT, an art exhibition located in the Wiesner Student Art Gallery on the second floor of the Stratton Student Center through November 15, 2024. This work challenges the common notion that technological innovation is the only solution to climate change, demonstrating that art-forward, interactive, communal experiences can deeply engage people on the issue. According to Sara, the sluggish progress on climate change mitigation is primarily a “people problem,” with elected decision-makers struggling to implement solutions “in a timely manner.” To this end, Interwoven reminds viewers of the direct, hands-on role they play in halting climate change.

Academic Silos and Interdisciplinarity

Sara describes the common experience of feeling “siloed” into a field of study, hindering interdisciplinary efforts. Nonetheless, Sara has actively branched out—she is a mechanical engineering student, and also focuses on sustainable design and computation. While she was an MIT undergrad, she was almost “exclusively taking classes within [materials science and engineering]” since many interesting interdisciplinary classes would not meet degree requirements. Marwa also notes that by showcasing the power of collective action in the climate change and sustainability space, the trio hopes to unite “people who have similar interests across departments” and “different interests in the same departments,” blurring some of these boundaries.

Interwoven: Collective Expression

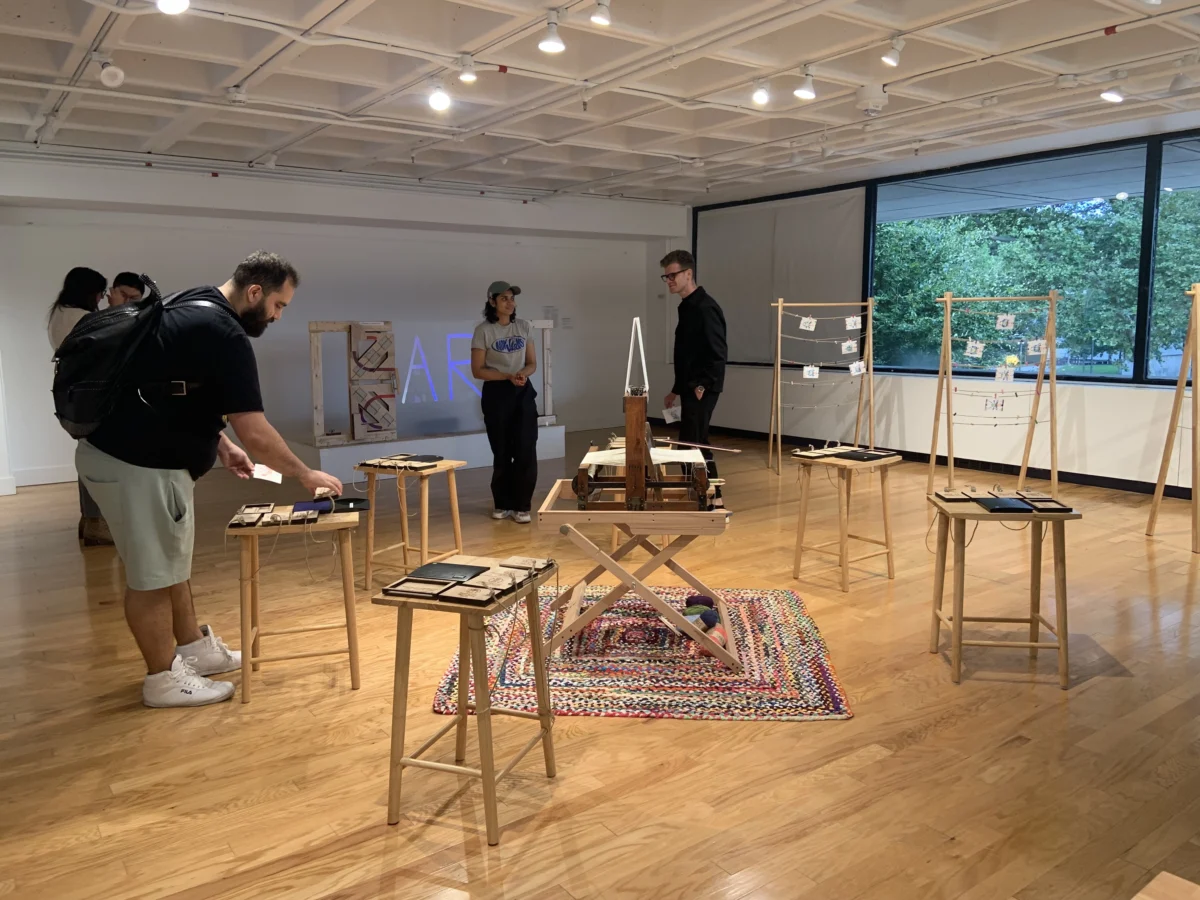

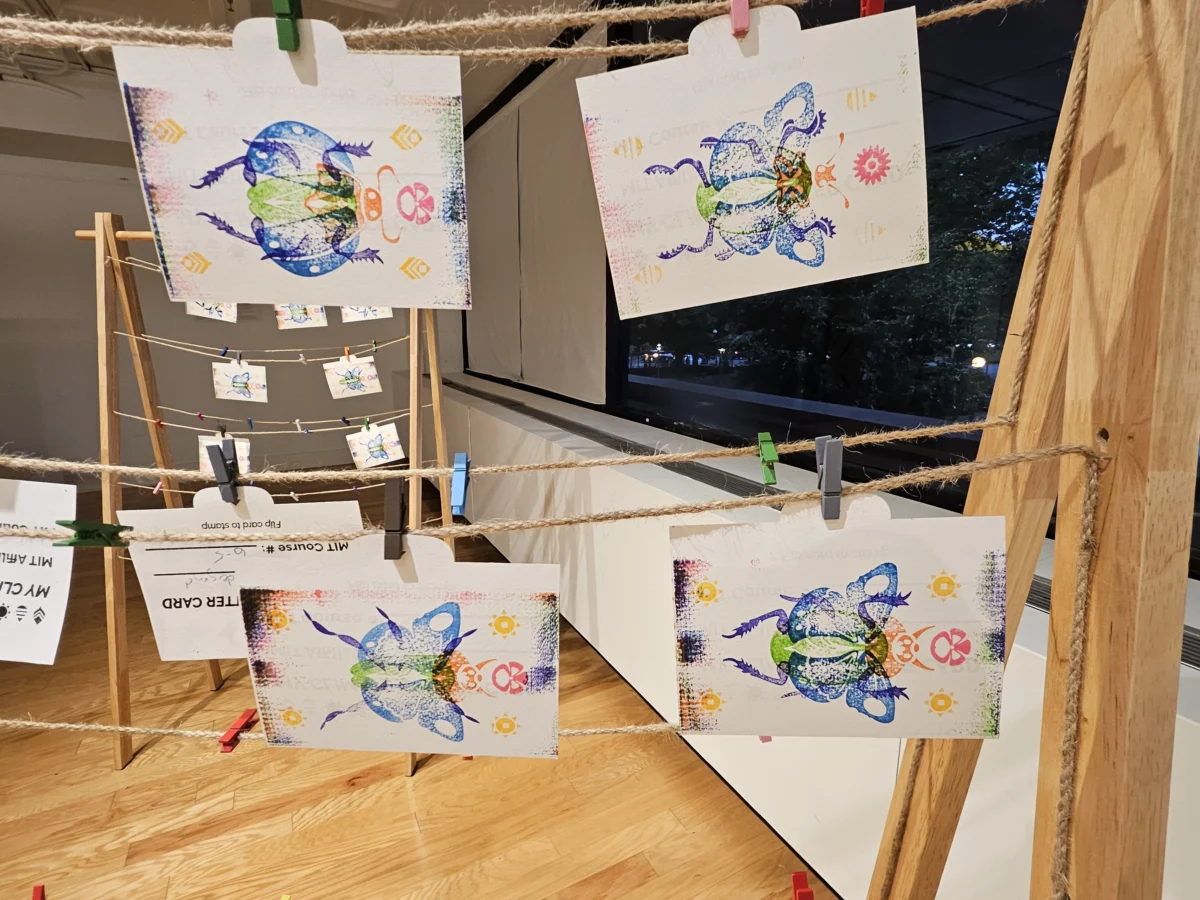

The exhibit itself is structured around activity, not passivity, compelling participants to reflect on their personal priorities within the sustainability space. Participants are asked six questions, and depending on their answers, they use rubber stamps on cardstock to print colorful bug body parts—wings, antenna, and so on. The final result is a unique “climate critter” that represents a personal climate persona. According to Supreetha, the motivation for this activity was the group’s desire to consolidate a persona into something “people can touch and see,” mimicking how the MIT community can have a “hands-on” role in mitigating climate change. After printing, participants hang up their critters in the gallery. The artists encourage visitors to look for an existing “twin” critter, which means that some other person at MIT shares your strategy for affecting climate change.

In the center of these six stamping stations is a loom containing a half-made silk tapestry. In contrast to the stamped critters, which collect and display individual climate personas, the weaving takes the “exact opposite perspective,” encoding information for each question from all participants in the stamping project. In the weaving, different colors represent the distribution of answers on the cards, similar to a bar graph. The silk tapestry also represents the evolution from critter to cocoon, paralleling the first step of metamorphosis.

Art, Collaboration, and the Future

The back of the gallery contains an interactive video component that requires two people to activate. The two people must flank the display, and then simultaneously slide and unfold its wooden paneling. Once unfolded, the fully metamorphosed critters on-screen fly away, and the projection alternates between four words: Cause, Care, Climate, and Change. The two-person nature of this artwork represents the beautiful possibilities that we unlock when we collaborate, even with people of wildly different viewpoints. When these critters and the ideas they represent are interwoven we unlock possibilities in our shared sustainability journey.

Taking Interwoven as a whole, Sara articulates the exhibit’s broader purpose in stimulating dialogue about how technology can be deployed in the context of sustainability and climate change. To Supreetha, the manual, hands-on nature of this exhibit reinforces the importance of slow, thoughtful actions, noting that “the art itself is in the participation.” All three artists hope that the project also inspires general institutional support for interdisciplinary efforts, particularly those that bridge science and engineering with the arts. As Marwa succinctly concludes, “When we’re all working together, we can create change.”

Written by Alor Sahoo

Editorial direction by Leah Talatinian