The Signature Hack

At the 2017 Hacking Arts Festival, MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST) Visiting Artist Agnieszka Kurant worked with a team of MIT graduate students and researchers to create a “signature hack,” a new feature of the festival, designed to be a source of inspiration to students competing in the annual arts-focused hackathon. Together with Agnes Cameron, Ishaan Grover, Adam Haar Horowitz, Tim Robertson, Owen Trueblood, and Gary Zhang, Kurant developed a project influenced by the ideas of collective intelligence and emergence.

Horowitz, a Master’s student in the Fluid Interfaces group in the MIT Media Lab, acted as the Hacking Arts Creative Lead and assembled the team for the Signature Hack. This team and Kurant worked together for a month prior to Hacking Arts to hone the idea for the space and scope of the 24-hour hackathon. Horowitz chose team members based on mutual intellectual interests and complementary skills. He points out, “Owen makes machines that make art, Agnes is an expert in swarm behavior, Ishaan researches machine intelligence, Gary works and writes between art, technology and organisms, and I work with sentiment analysis and sentiment creation.” As for Kurant, she has long been fascinated by the synchronization of organisms like slime mold, or certain colonies of bacteria, or fireflies that flash in unison.

The Animal Internet

For Hacking Arts, the team built on their shared interest in collective behavior and focused on a recent popular phenomenon, the animal internet. For those unfamiliar, the animal internet refers to webcams placed by scientists in various locations, which allow people to view wild animals in their natural habitats.

Kurant says, “millions of people follow these animals, give them names, create Facebook pages or fan pages for them, and invent parallel lives for these creatures.” For many, she adds, their primary contact with nature is mediated in this way.

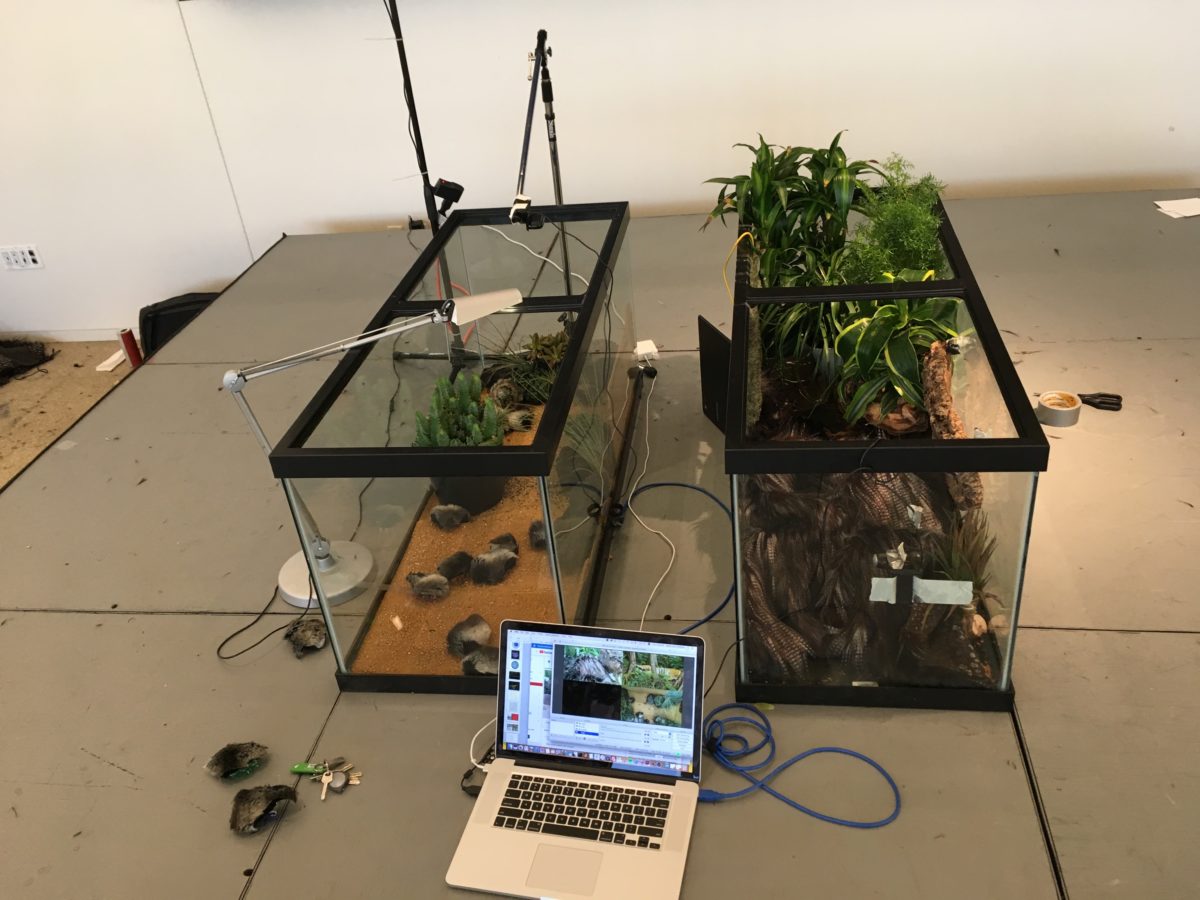

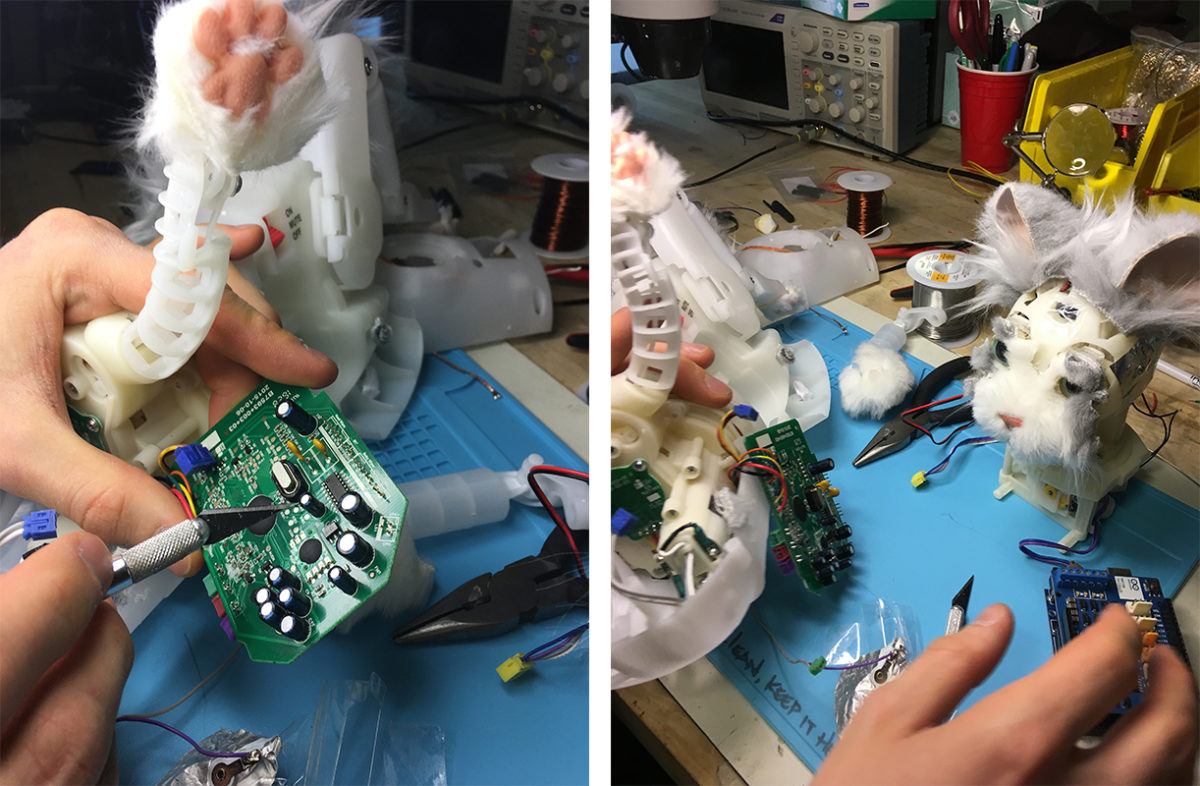

With her team, Kurant made two fictional animals, a singular feathered one and a swarm of robotic gerbils. She was struck by how little needs to be done to emulate life—a few feathers here, some patches of fur there, attached to robots and placed in a terrarium. When viewed alongside tigers and polar bears via livestream, these animatronic creatures are fairly convincing. The fictional animals were operated by real people—one using Amazon Mechanical Turk workers and another using data collected from Twitter about current protest movements.

Crowdsourced Movement

The Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing platform constitutes approximately 5 million people worldwide. In her work, Kurant wants to bring attention to this new working class, who are not unionized and vulnerable to exploitation. For this project, the workers were represented as one collective unit, or one animal. The workers received tasks based on their emotional state. They were asked three multiple choice questions to determine whether they felt sleepy, happy, unhappy or energized; the prevailing responses directed the animal’s movement. Kurant likened her fictional animal to a tamagotchi, the popular Japanese egg-shaped toy, which is operated by many people.

The second set of animals, which resembled gerbils, were powered by a sugarscape model, and fed with data scraped from Twitter, pertaining to social behavior associated with various protest movements—from Catalonian independence to Black Lives Matter to Occupy Wall Street. “We measured the temperature of these protest movements and whether they were positive or negative,” said Kurant. “Then feeding this data back into this sugarscape powers the movement of the swarm of animatronic gerbils.”

Ishaan Grover, who collected the data from Twitter said, “There are protests movements all over the world and people are posting tweets. So we go on twitter and every ten seconds we find out what is the collective sentiment. Every ten seconds, it updates and we calculate the average sentiment of people all over the world who are tweeting about protests and then that feeds into sugarscape.”

Agnes Cameron, who built the sugarscape model, explained that the semantic data taken from Twitter controls the environmental variables, which in turn control the gerbils’ movement.

The project gives physical form to invisible forces, like social movements and collective intelligence. And the collectively powered fictional animals that are operated by thousands of people can also be watched by thousands of people via livestream alongside the animal internet.